Cash conversion cycle in smes

Post on: 25 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

FUNDACIÓN DE LAS CAJAS DE AHORROS

ISSN: 1988-8767

La serie DOCUMENTOS DE TRABAJO incluye avances y resultados de investigaciones dentro de los pro-

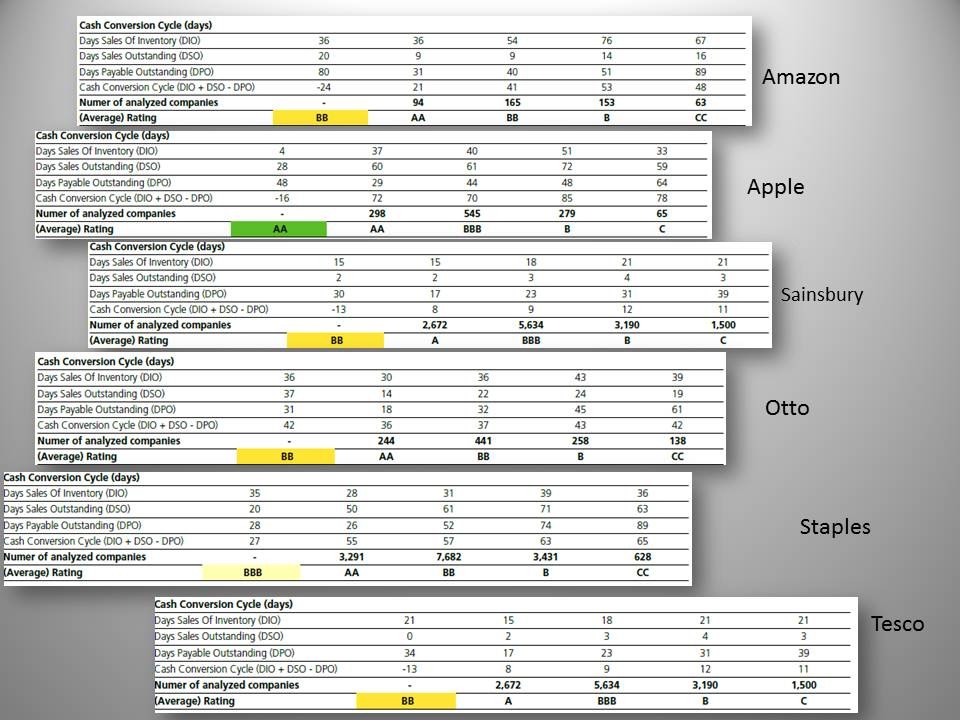

This paper examines the determinats of Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) for small and

medium-sized firms. It is found that these firms have a target CCC level to which they

attempt to converge, and they try to adjust to their target level quickly. The results also

1. INTRODUCTION

The corporate finance literature has traditionally focused on the study of long-term

financial decisions such as the structure of capital, investments, dividends and firm

valuations. However, Smith (1980) suggested that working capital management is

important because of its effects on the firm’s profitability and risk, and consequently its

value. Following this line of argument, some more recent studies have focused on how

reduction of the measures of working capital improves the firm’s profitability (Jose et

al. 1996; Shin and Soenen, 1998; Deloof, 2003; Padachi, 2006; García-Teruel and

Martínez-Solano, 2007; and Raherman and Nasr, 2007).

In contrast with these studies, much less attention has been given to the

determinants of working capital management; a search of the literature identified only

two previous studies (Kieschnick et al. 2006; and Chiou et al. 2006) focused on larger

firms, but there is no evidence from SMEs, despite the fact that efficient working capital

management is particularly important for smaller firms (Peel and Wilson, 1996; Peel et

al. 2000). Most of an SME’s assets are in the form of current assets, while current

liabilities are one of their main sources of external finance, because of the financial

investment in inventories and trade credit granted. In addition, companies may get

important discount for early payments, and therefore reduce supplier financing.

However, keeping a high CCC also has an opportunity cost if firms forgo other more

productive investments to maintain that level. The paper therefore develops a partial

adjustment model to determine the firm characteristics that might affect the Cash

Conversion Cycle in SMEs, using a panel of 4076 Spanish SMEs over the period 2001-

2005. Hence, this study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, unlike

previous works, we develop a partial adjustment model that allows us to confirm

whether SMEs have a target Cash Conversion Cycle level. Secondly, the study

estimates the model using two-step General Method of Moments (GMM), which allows

the researchers to control for possible endogeneity problems. Moreover, as has been

pointed out above, this paper provides evidence on the determinants of the CCC for

SMEs, where the capital market imperfections are more serious.

The findings for the present study are that SMEs have a target Cash Conversion

2. DETERMINANTS OF WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT AND THE

EXPECTED RELATIONSHIPS

In perfect capital markets, investment decisions are independent of financing decisions

and, hence, investment policy only depends on the availability of investment

opportunities with a positive net present value (Modigliani and Miller, 1958). In the

neoclassical model, companies have unlimited access to sources of finance and

investment, so firms with opportunities for profitable investment that exceed their

available cash flow would not be expected to invest any less than firms with the same

opportunities and higher cash flow, because external funds provide a perfect substitute

for internal resources. In this situation, a larger Cash Conversion Cycle would not have

an opportunity cost, because firms could obtain external funds without problems and at

a reasonable price. However, internal and external finance are not perfect substitutes in

practice. External finance, debt or new share issues, may be more expensive than

internal finance because of market imperfections. In these circumstances, a firm’s

(Smith, 1987). This argument was also supported by Deloof and Jegers (1996), who

suggested that granting trade credit stimulated sales because it allowed customers to

assess product quality before paying. It also helps firms to strengthen long-term

relationships with their customers (Ng et al. 1999), and it incentivizes customers to

acquire merchandise at times of low demand (Emery, 1987). Moreover, from the point

of view of accounts payable, companies may get important discounts for early

payments, reducing supplier financing (Wilner, 2000; Ng et al. 1999). However,

maintaining a high Cash Conversion Cycle also has an opportunity cost if the firm

forgoes other more productive investments to keep that level and, as Soenen (1993)