Capital Allocation Decisions Bringing the Board of Directors on Board Deloitte Risk Compliance

Post on: 25 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Capital Allocation Decisions: Bringing the Board of Directors on Board

How does management decide where to invest capital given the wide array of investment alternatives ranging from mergers and acquisitions (M&A), to dividends and share repurchase programs, to organic growth opportunities? And what is the board’s role in helping to shape those investment decisions?

Given limited capital and higher expectations from shareholders, the board can help serve the interests of investors by guiding management to direct capital to the highest return alternatives after providing appropriate oversight to help management fully consider and manage the risks of the enterprise.

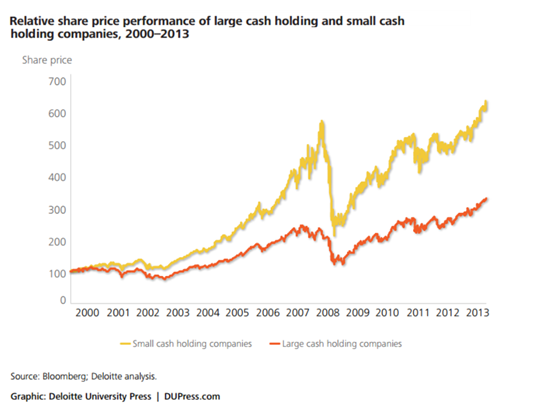

Continued uncertainty about the economy and increased regulation across a number of industries have required a more informed and efficient use of capital. Shareholders are looking for stewardship by the board to oversee how the company deploys financial resources and allocates capital, especially given that cash on the balance sheets of U.S. public companies is at an all-time high. Increasingly complex transactions are also causing directors to take a closer look at how capital allocation decisions are made.

The Board’s Role in Capital Allocation

Deciding where to focus investment requires a productive working relationship between management and the board. Working with the board, management is responsible for defining strategy, prioritizing investment opportunities—often across multiple businesses, functions and geographies—as well as executing strategy and delivering results. The board provides a critical role in overseeing and holding management accountable for results. The board also adds value through the collective wisdom that seasoned directors contribute through their advice to management.

In fulfilling its responsibility to shareholders, the board’s oversight of capital allocation should encompass not just the process itself, but also the tools, talent, methodologies and cadence of how such decisions are made. The process should incorporate checkpoints and require, for example, board approval of annual budgets or investments exceeding a certain size or those investments outside the standard profile as defined by the company. Policies should be established where special board committees are required either on a one-time or a standing basis, to consider transactions of a certain size or type or where director independence is important to the board fulfilling its responsibilities to shareholders.

Whatever the process, it should allow for an appropriate exchange of ideas between management and the board, and provide the board with adequate information to challenge management’s thinking in a constructive manner to make sure that decisions are well informed and in the best interests of stakeholders. In doing so, it is necessary to use a rigorous analysis, often with a standard framework, and to take a meta-view on how to best deploy capital across the organization, especially given the full range of investment options available.

Organizations are moving beyond a static approach to budgeting and capital allocation and taking a more dynamic approach focused on capital efficiency. There is value in management having the strategic flexibility to change course as new information is learned about the competitive environment and not being constrained by the annual budgeting cycle. It is difficult to achieve a dynamic process that includes an integrated framework across all businesses, functions and geographies to optimize the total portfolio of corporate investments. However, increases in capital efficiency can typically be realized by taking incremental steps, say, by focusing on a particular line of business or type of project and then building on that base over time. This can serve the interests of shareholders by increasing management flexibility, but presents a challenge to the board in fulfilling its oversight role and makes having a well-defined process and associated rules of the road even more important.

Increased transparency and governance could be cited as a trend with many corporate initiatives or changes, and this is also true for capital allocation. With regard to capital allocation, there is a dual role for the board: first, to serve by increasing shareholder value through advice, counsel and strategic direction; and, second, to protect by safeguarding shareholder value through governance and oversight. Directors can contribute to the capital allocation process by weighing in on investment decisions and by serving as a sounding board for management. Given their wide range of experiences, directors bring their expansive experience and capabilities to the boardroom table. However, directors are not expected to manage the capital allocation process; this is the responsibility of management.

The board of directors is able to serve shareholders with capital allocation decisions by:

—Overseeing management, including providing the flexibility for management to implement the defined strategies.

—Being comfortable with the qualifications and competence of management and the robustness of the process.

—Challenging business plans and strategy and reviewing alternatives.

—Evaluating the qualifications of the investment team. Overseeing major capital decisions as the representative of stakeholders.

—Holding management accountable for actual versus expected performance.

Taking into account these ways in which directors can help to serve the company, the board can add value to the capital allocation process.

The board of directors also can help to protect the corporation through its responsibilities that encompass both the duty of care and the duty of loyalty.

With regard to capital allocation decisions, the duty of care involves directors employing an informed, deliberate and good-faith process in their decision-making and oversight responsibilities. In return, directors may be protected by the business judgment rule, which is a legal presumption that, when making decisions, directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action was taken in the best interest of the company.

The duty of loyalty provides that directors are free of deriving personal benefits from the outcomes of their decisions. The duty of loyalty allows the director to be objective, independent and, like the duty of care, shows that the director acted in the best interest of the company.

Maintaining a Dialogue Between Management and the Board

While the oversight responsibilities of the board of directors continue to expand and evolve, a fundamental role at the heart of advising on strategy is the board’s role in capital allocation and related risks. The board can play a fundamental role in the capital allocation process through its oversight function, including participating in strategy development, examining risks, comparing strategy to results and working with management on key investment terms, among other areas. Leveraging the experiences of directors can be useful and help to provide further insights into investment decisions.

May 2, 2013, 12:01am

Follow us on Twitter @DeloitteRisks