Bull Market Stock Funds Flows Don t Show It

Post on: 11 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Sam Mamudi

Updated March 11, 2010 12:01 a.m. ET

Investors often flee the stock market and then jump back in, but too late for their own good.

ENLARGE

Wall Street’s iconic bull statue, standing amid the shadows near the Big Board late last year, seems to capture at once the stock market’s latest bullish run as well as mutual-fund investors’ seeming disregard for it. Bloomberg News

The question is whether the losses were so big that they scared investors away from stocks not just for the next few months, but also for years.

I don’t know if we’re seeing the demise of actively managed mutual funds—if we are seeing a big change—but a lot of people seem to have decided to stay away from stock funds, said Tom Roseen, senior analyst at research firm Lipper Inc.

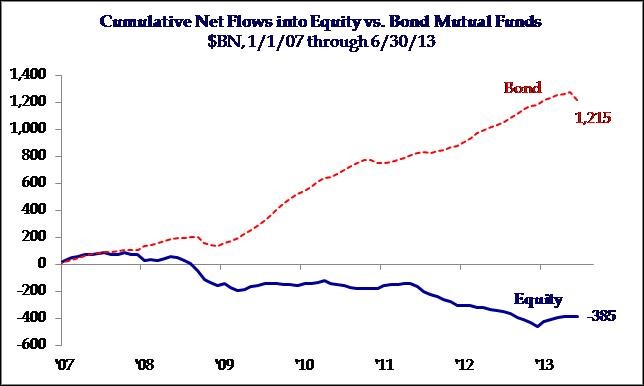

From March 1, 2009, through Jan. 31, stock mutual funds saw net inflows of $21.22 billion—trivial for a sector that has about $4 trillion in assets. In the same period, bond funds saw net inflows of $328 billion.

But those numbers don’t tell the whole tale. While stock mutual funds saw poor inflows in the first 11 months of the bull market, some categories fared much better than others.

International stock funds saw $46.5 billion in net inflows—fairly substantial flows for a category that had about $760 billion in total assets at the end of January, according to Lipper. Gold and natural-resources funds, meanwhile, only saw net outflows in one month during the period—July—and the $40 billion category ended the 11 months with net inflows of $4.2 billion.

The bulk of the outflow has been from U.S. stock funds, which means investors have been withdrawing money out of the market even as prices have risen sharply. While surprising, it may suggest investors are being careful in how they allocate cash.

As Mr. Roseen noted, while large-cap U.S. stocks are often seen as defensive in a recession, the recent crisis quashed that perception. A weak dollar, higher prices for gold and natural resources and bargain-hunting may have led people into alternatives such as developed and emerging international markets.

After the routing the international market took in 2008, I think many investors saw some unique opportunities to buy securities at deeply discounted prices. For others, it might have been simply performance-chasing—after all, Latin American funds were up 113% in 2009 and emerging-markets funds climbed 76%, Mr. Roseen said.

The overall flow numbers also fit a pattern. This is the fourth bull market since 1987, according to Standard & Poor’s Equity Research. Each time, net inflows into stock funds have been slow to get going before jumping in the second year.

During the first 12 months of 1987’s bull market, for example, stock funds saw $16 billion in net outflows, but that was followed by a cascade of more than $4 billion in new money over the following year. A similar surge in 1990’s bull market: Net inflows were roughly $26 billion in the first year and more than $70 billion over the next year. And the first year of the bull market that began in late 2002 saw about $90 billion in net stock fund inflows, jumping to $190 billion in the second year.

The combination of inflows into some categories together with bull-market history does suggest it would be premature to write off interest in stock funds. But there is another factor to consider: the threat to traditional funds from exchange-traded funds.

From March 2009 through January, stock ETFs saw net inflows of $14 billion. That was despite net outflows of more than $18 billion in January, which was likely due to investors’ tax maneuvering. Take out January’s numbers, and stock ETFs saw almost $33 billion in net inflows in the first 10 months of the bull market, a sizeable chunk of the roughly $600 billion in all stock ETFs.

Mr. Roseen said this suggests some people feel let down by active management and are choosing passive, index-linked funds. It also might be that the liquidity of ETFs, which are bought and sold on an exchange, appeals to skittish investors.

I think a lot of people look at it and they want to be able to get in and out of the market quickly, and ETFs are more nimble, he said.

Will investors return this year in greater numbers, repeating the pattern of previous bull markets?

Much depends on whether the economy shows clearer signs of being on the mend. Unemployment is hovering at about 10%, the consumer-sentiment index fell in February and both new-home sales and pending home sales dropped in January. Against this backdrop, it isn’t hard to see why many investors don’t trust the market rally.

We don’t foresee a strong rebound in the economy; we think it’ll just bounce along, and there’ll be good days and bad days, said Barry James, president and chief executive of James Investment Research, an Alpha, Ohio, investment adviser with about $2 billion in assets under management. There’s a disconnect [between the market and the economy] and I think we’re going to see another major shift out of stock funds.