Aughts were a lost decade for workers

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Graphic

Washington Post Staff Writer

Saturday, January 2, 2010

For most of the past 70 years, the U.S. economy has grown at a steady clip, generating perpetually higher incomes and wealth for American households. But since 2000, the story is starkly different.

The past decade was the worst for the U.S. economy in modern times, a sharp reversal from a long period of prosperity that is leading economists and policymakers to fundamentally rethink the underpinnings of the nation’s growth.

It was, according to a wide range of data, a lost decade for American workers. The decade began in a moment of triumphalism — there was a current of thought among economists in 1999 that recessions were a thing of the past. By the end, there were two, bookends to a debt-driven expansion that was neither robust nor sustainable.

There has been zero net job creation since December 1999. No previous decade going back to the 1940s had job growth of less than 20 percent. Economic output rose at its slowest rate of any decade since the 1930s as well.

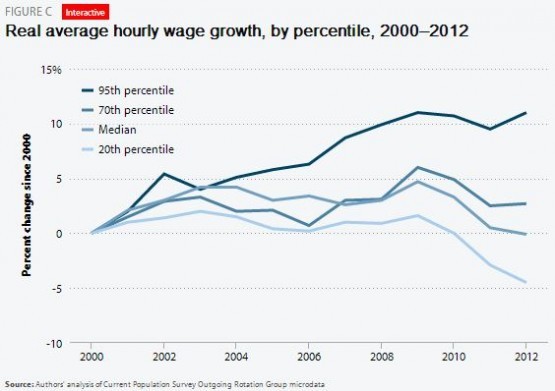

Middle-income households made less in 2008, when adjusted for inflation, than they did in 1999 — and the number is sure to have declined further during a difficult 2009. The Aughts were the first decade of falling median incomes since figures were first compiled in the 1960s.

And the net worth of American households — the value of their houses, retirement funds and other assets minus debts — has also declined when adjusted for inflation, compared with sharp gains in every previous decade since data were initially collected in the 1950s.

This was the first business cycle where a working-age household ended up worse at the end of it than the beginning, and this in spite of substantial growth in productivity, which should have been able to improve everyone’s well-being, said Lawrence Mishel, president of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank.

Question of timing

The miserable economic track record is, in part, a quirk of timing. The 1990s ended near the top of a stock market and investment bubble. Three months after champagne corks popped to celebrate the dawn of the year 2000, the market turned south, a recession soon following. The decade finished near the trough of a severe recession.

But beyond these dramatic ups and downs lies an even more sobering reality: long-term economic stagnation. The trillions of dollars that poured into housing investment and consumer spending in the first part of the decade distorted economic activity.

Capital was funneled to build mini-mansions in Sun Belt suburbs, many of which now sit empty, rather than toward industrial machines or other business investment that might generate economic output and jobs for years to come.

The problem is that we mismanaged the macroeconomy, and that got us in big trouble, said Nariman Behravesh, chief economist at IHS Global Insight. The big bad thing that happened was that, in the U.S. and parts of Europe, we let housing bubbles get out of control. That came back to haunt us big-time.

The housing bubble both caused, and was enabled by, a boom in indebtedness. Total household debt rose 117 percent from 1999 to its peak in early 2008, according to Federal Reserve data, as Americans borrowed to buy ever more expensive homes and to support consumption more generally.