Analyzing The PriceToCashFlow Ratio_2

Post on: 12 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

* * * * * * * VALUATION MEASURES * * * * * * *

The measures shown below, esp. P/BV, P/CF and P/ SALES, are considered to be good supplements to the P/E ratio when conducting fundamental valuation. None has the theoretical base that the P/E ratio has, but they can provide additional insights into relative valuation changes for a stock. For each ratio (P/BV, etc.), you should examine the company ratios over time relative to the same ratio for the market and for the firm�s industry. You should look for: relationships that are not justified by the fundamental differences in the growth rate of book value or cash flow and differences in risk, or changes in the normal relationships that are not supported by changes in these fundamental factors. (Of course, we use the Discounted Dividend models, e.g. constant growth model, for absolute valuation.)

As an example of the first case, assume that a firm�s P/BV ratio was 0.8 compared to a market ratio of 3.0 and an industry ratio of 1.9. You would analyze the firm to see if these differences were justified. A difference that was not justified by differences in expected growth and risk might indicate an under-priced stock. As an example of an alternative case, assume a stock�s P/BV ratio consistently had matched the market ratio, but recently the stock�s P/BV ratio increased by 50 percent relative to the market with no change in the company�s relative growth or risk. You would probably consider this a possible indicator of overvaluation. These examples would be only bits of evidence in a full-scale analysis, but they can be used as additional indicators of relative valuation.

fnews.yahoo.com/isdex/99/01/14/morning_990114.html.) The same can be said about the oil and gas stocks since BV might significantly understate the real worth of the assets. For extractive industries there is no predictable relationship between BV of assets and the comany’s sales and stock price. Value is more related to proven reserves, still underground, than the historical cost shown on the books. Hence, Price to Proven Oil and Gas Reserve, per share may give a reasonable valuation measure.

www.fool.com/School/IntroductionToValuation.htm.

1. Price to Book Value (P/BV) Ratio

The price/book value ratio is used extensively in the valuation of many stocks. This measure is especially suitable for valuing bank stocks because banks often have similar book values and market values. (Bank assets include investments in government bonds, high-grade corporate bonds or municipal bonds, along with commercial, mortgage, or personal loans that are generally expected to be collectible.) Under ideal conditions, the price/book value (P/BV) ratio should be close to 1. Book values reflect historical costs, but price discounts the future. With falling interest rates, this ratio has increased over time. Even banks typically sell at above book value, though it would not be surprising to find a P/BV ratio of less than for a bank with Problem Loans. (Compare this ratio for banks with loans to Asia or Latin America vs. others). It is also possible to find a P/BV ratio above 1 for a bank with significant growth opportunities due to, say, its location, because it is a desirable merger candidate, or because its use of technology in banking.

Industrial firms can easily have a P/BV ratio above 1.0. This is so because their asset book values tend to underestimate their replacement costs.

The P/BV ratio for the S&P 400 was about 1.3 during 1977-1982. It subsequently has increased steadily to record levels in 1994 and 1995.

DECISION RULE. Stocks with low P/BV ratios should outperform high P/BV stocks. Barr Rosenberg, Kenneth Reid, and Ronald Lanstein [�Persuasive Evidence of Market Inefficiency,� Journal of Portfolio Management 11, no. 3 (Spring 1985): 9-17] and Eugene F. Fama and Kenneth R. French [�The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,� Journal of Finance 47, no 2 (June 1992): 427-4509] examined this strategy and found that stocks with low P/BV ratios experienced significantly higher risk-adjusted rates of return than the average stock. (Their results did not provide much support for beta as an explanatory variable, but the results indicated that both the size of firms and the ratio of book value to market value (BV/MV) of equity were significant explanatory variables. Moreover, they contended that the BV/MV ratio was the single best variable.)

It has been shown that the P/BV ratio is positively impacted by future growth prospects and risk factors similar to the P/E ratio, and that the P/B ratio is a function of the expected level of profitability on book value, which we know is related to ROE.

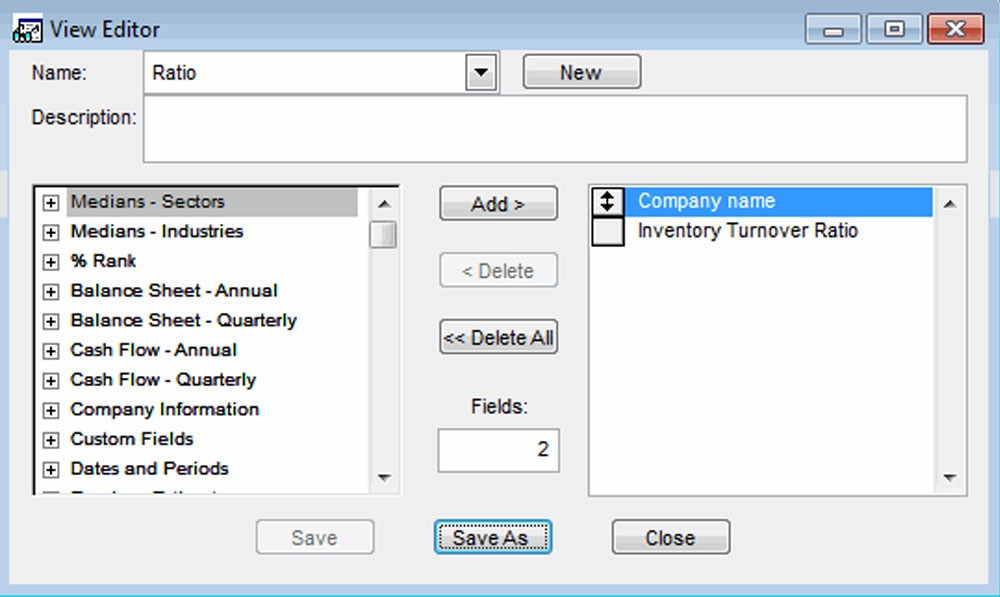

2. Price to Cash Flow (P/CF) Ratio

Another measure of relative value, the price/cash flow ratio, is used to supplement the P/E ratio because a firm�s cash flow typically is subject to less accounting manipulation than reported earnings. Also, cash flow has become an important measure of performance, value, and financial strength because numerous academic studies have shown that various cash flow measures can be used to predict both success and future problems. Also, cash flow data have become more accessible because firms currently publish statements of cash flow, along with their income statements and balance sheets.

Developing benchmark values for these ratios is important because, similar to P/Es and P/BV ratios, they are relative measures of value. Therefore, you should understand the comparable values over time for the market as represented by the S&P 400 and the relevant industry. For demonstration purposes, availability of data leads us to define cash flow per share as net income per share plus depreciation (and amortization) expense per share. This traditional measure of cash flow is intended to reflect earnings plus non-cash expenses; depreciation is the largest non-cash expense that can be identified.

3. Price to Sales Ratio

What happened when earnings are negative but there are growth opportunities? From Steve Harmon’s column of January 12 in Yahoo. Most surprising move in the group comes from Compaq (NYSE:CPQ — news). which owns Alta Vista. Compaq agreed to acquire shopping site Shopping.com for $220 million cash, or about 41x estimated 1998 sales. We think Compaq was willing to pay a premium here for the technology and the time factor.

4. Price to Breakup Value

Breakup value is the estimated market value of selling divisions of a firm to others. An increase in the estimates of breakup value has caused the average P/BV ratio for industrial firms to experience a volatile increase over time. An important measure of evaluating if some of the parts would be more valuable than the whole company.

5. Dividend Yield (Div/Price)

Dividend to Price ratio is considered an important measure. Companies with high ratios tend to be more stable and are considered to outperform their peers.

6. Growth Rate Relative to P/E

This measure has strong following on Wall Street. Analysts argue that firms with a growth rate exceeding their P-E ratio are potentially good investment values and those with grwoth rates less than their P/E are poor values.

7. Tobin’s Q = Price to Replacement of Assets

This measure is explained in Chapter 27 of Brealey Myers.

8. MEASURES OF VALUE-ADDED

In addition to the Disc. Dividend Models (DDM), which feeds into the earnings-P/E ratio valuation technique and the supplementary P/BV and P/CF ratios, there has been growing interest in a set of performance measures referred to as �value-added.� An appealing characteristic of these value-added measures of performance is that they are directly related to the capital budgeting techniques used in corporation finance. Specifically, they consider economic profit, which is analogous to the net present value (NPV) technique used in corporate capital budgeting. These value-added measures are mainly used to measure the performance of management based on their success in adding value to the firm. Notably, they also are being used by security analysts as possible indicators of future equity returns based on the logic that superior management performance should be reflected in a company�s stock returns. In the subsequent discussion, we concentrate on two measures of value-added: economic value-added (EVA) and market value-added (MVA) pioneered by Stern and Stewart.

Economic Value-Added (EVA)

As noted, this measure of value-added is closely related to the net present value (NPV) technique. Specifically, with the NPV technique you evaluate the expected performance of an investment by discounting the future cash flows from a potential investment at the project�s cost of capital (or WACC if the whole firm or project of average risk) and compare this sum of discounted future cash flows to the cost of the project. If the discounted cash flows are greater than its cost, the project is expected to generate a positive NPV, which implies that it will add to the value of the firm and therefore it should be undertaken. In the case of EVA, you evaluate the annual performance of management by comparing the firm�s net operating profit less adjusted taxes (NOPLAT) to the firm�s total cost of capital in dollar terms, including the cost of the equity. In this analysis, if the firm�s NOPLAT during a specific year exceeds its dollar cost of capital, it has a positive EVA for the year and has added value for its stockholders. In contrast, if the EVA is negative, the firm has not earned enough during the year to cover its cost of capital and the value of the firm has declined. Notably NOPLAT indicated what the firm has earned for all capital suppliers and the dollar cost of capital is what all the capital suppliers required—including the firm�s equity holders. The following summarizes the major calculations.

EVA =

(A) Adjusted Operating Profits before Taxes

minus (B) Cash Operating Taxes

equals Net Operating Profits Less Adjusted Taxes (NOPLAT)

minus (D) The Dollar Cost of Capital

equals (E) Economic Value-Added (EVA)

In turn, these items are calculated as follows:

Plus: Accumulated Goodwill Amortized

Equals: Capital

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) =

(Book Value of Debt/Total Book Value) x (the Market Cost of Debt) (1 — Tax Rate)

(Book Value of Equity/Total Book Value) x (Cost of Equity)

(Cost of equity is based on the CAPM using the prevailing 10-year Treasury bond as the RFR, a calculated beta, and a market risk premium between 3 and 6 percent.)

(D) Dollar Cost of Capital = Capital x WACC

(E) Economic Value-Added (EVA) =

Net Operating Profits Less Adjusted Taxes (NOPLAT) Minus (D) Dollar Cost of Capital

EVA RETURN ON CAPITAL. The prior calculations provide a positive or negative dollar value, which indicates whether the firm earned an excess above its cost of capital during the year analyzed. There are two problems with this annual dollar value for EVA. First, how does one judge over time if the firm is prospering relative to its past performance? Although you would want the absolute EVA to grow over time, the question is whether the rate of growth of EVA is adequate for the additional capital provided. Second, how does one compare alternative firms of different sizes? Both of these concerns can be met by calculating an EVA return on capital equal to:

EVA/Capital

You would want this EVA rate of return on capital for a firm to remain constant over time, or ideally grow. Also, using this ratio you can compare firms of different sizes and determine which firm has the largest economic per dollar of capital.

MARKET VALUE-ADDED (MVA)

In contrast to EVA, which generally is an evaluation of internal performance, MVA is a measure of external performance—how the market has evaluated the firm�s performance in terms of the market value of debt and market value of equity compared to the capital invested in the firm.

Market Value-Added (MVA) = (Market Value of Firm) — Capital

— Market Value of Debt

— Market Value of Equity

Again, to properly analyze this performance, it is necessary to look for positive changes over time—i.e. the percent change each year. It is important to compare these changes in MVA each year to those for the aggregate stock and bond markets because these market values can be impacted by interest rates and general economic conditions.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN EVA and MVA

Although EVA is used primarily for evaluating management performance, it also is being used by external analysis to evaluate management with the belief that superior internal performance should be reflected in a company�s stock performance. Several studies have attempted to determine the relationship between the two variables (EVA and MVA), and the results have been mixed. Although the stock of firms with positive EVAs has tended to outperform the stocks of negative EVA firms, the differences are typically insignificant and the relationship does not occur every year. This poor relationship may be due to the timing of the analysis (how fast EVA is reflected in stocks) or because the market values (MVAs) are affected by factors other than EVA—e.g. MVA can be impacted by market interest rates and by changes in future expectations for a firm not considered by EVA, i.e. it appears that EVA does an outstanding job of evaluating management�s past performance in terms of adding value. While one would certainly hope that superior past performance will continue, there is nothing certain about this relationship