Amazon earnings How Jeff Bezos gets investors to believe in him

Post on: 5 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

How Jeff Bezos won the faith of Wall Street.

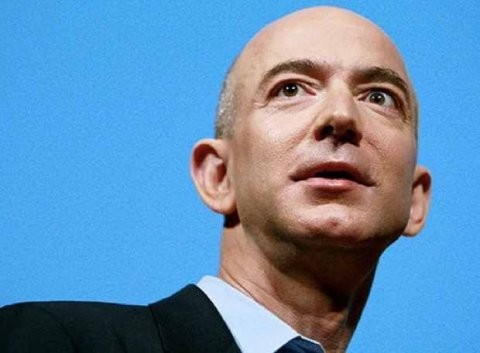

24BOX_JeffBezos2013.jpg.CROP.original-original.jpg /% Investors were willing to believe in Jeff Bezos, so Bezos could afford to stop proving that he knows how to turn a profit.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Getty Images.

E-commerce was king this past holiday season, with Christmas surge orders overwhelming UPSs systems and forcing $100 million in upgrades to prevent future fiascos. So it was no surprise on Jan. 30 when Amazon reported it had become even more enormous than ever before. According to its latest earnings report, the online shopping giant’s net sales increased 20 percent compared with the previous holiday seasona number that would seem staggeringly high if it weren’t so routine for a company thats been growing rapidly for years. Yet the companys net income of $274 million for all of last year was tiny relative to its sales of $74.45 billion. Amazon’s profit margin was virtually nonexistent.

The prevailing theory in Silicon Valley is that its a mistake for new companies to focus too much on developing revenue. People use a social service such as Pinterest in part because many other people are using it. Under the circumstances, it makes sense for a company to focus first and foremost on building a great product and getting people to use it. Once youve reached a critical mass of users, then comes the time to think about revenue strategies. This approach sometimes fails (and its entirely possible that Snapchat or Instagram will prove to be white whales), but it has a great deal of logic and precedent behind it. Once upon a time, Google and Facebook were just impressive products with little or no revenue. Today theyre financial juggernauts that have parlayed their user bases into an advertising bonanza. Twitter is partway down this path, and others will follow.

In other words, growth first, revenue later is a risky business strategy, but a proven one. (The high level of risk is one reason the returns can be so great.)

Amazon doesnt fit this mold. For one thing, its hardly a young startup anymore. It was founded in 1995 and held its initial public offering way back in 1997. Most obviously, its not a firm with no revenue or with an unclear revenue strategy. You go to the website, you find items you might want to buy, and those items have prices next to them. If you decide you want to buy, you enter credit card information and get charged. Its the most boring revenue strategy in the world, and one of the oldest.

Whats more, its not as if Amazon has never been profitable. No large retailer has especially large profit margins, but for several years in the mid-aughts when the business was smaller, it obtained margins that were right in line with Walmarts.

Profits are in severe tension with the idea of pleasing customers—a profitable firm is, by definition, charging customers more than it needs to.

Photo by Thinkstock

Recent commentary has tended to draw a contrast between the companys rising share price and waning profits. The company barely ekes out a profit, spends a fortune on expansion and free shipping and is famously opaque about its business operations, wrote Meaghan Clark and Angelo Young in the International Business Times in December. yet investors continue to pour into the stock, pushing up the companys share price to $388, a nearly 400 percent rise since the end of the companys third quarter in September 2008.

This image of a firm that remains a darling of Wall Street despite a lack of profitability is tempting. But the truth is more likely the opposite. Amazon doesnt turn a profit because its a darling of Wall Street.

I once characterized Amazon as a charitable institution being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers. Bezos took issue with this in a letter to shareholders. His argument is that Amazon isnt a charity; its a businessa business whose strategy is to make its customers as happy as possible. And that, fundamentally, is what makes Amazon great. Profits are in severe tension with the idea of pleasing customersa profitable firm is, by definition, charging customers more than it needs to.

But of course, theres a reason that most companies try to make healthy profit margins: financial markets demand it. Only a Wall Street darling, a firm whose senior leadership has the confidence of markets, could get away with being as daring as Amazon is.

The timing of Amazons high-margin years is no coincidence. Amazon is, in a fundamental way, a child of the dot-com boom of the 1990s in a way that none of todays other technology giants are. Apple and Microsoft long predate the bubble, and Facebook was founded long after it burst. Google existed in a modest way in the 1990s, but didnt participate in go-go 90s finance; its 2004 IPO was a key step on the march of technology stocks back to respectability and credibility after the bubble burst.

But Amazon was right in the middle, born into the maelstrom of Clinton-era corporate finance. All stock prices soared in the late 90s. The historical memory of a tech bubble ignores the fact that very prosaic industrial firms like Ford have lost more than 50 percent of the 1999 peak value. But while investors smiled on all stocks in the 90s, they did take a special shine to technology stocks. An established company with a real business like AOL could obtain a valuation high enough to allow it to swallow all of Time Warner. And to attract investor enthusiasm, a startup didnt really need anything at allnot a business model or even a good productbeyond a .com at the end of its name. Under the circumstances, Amazon was no more under pressure to demonstrate profitability than was Pets.com or Kozmo.com or any of the other in-retrospect-hilarious white elephants of the era.

Amazon didnt avoid the corporate graveyard by refusing to indulge in the mania of its founding era. Like many other dot-coms, it steadily lost money in pursuit of growth. It was a well-timed bond offering in February 2000 just before market sentiment turnedlet Amazon ride out the cash crunch that brought down so many other firms.

That money bought Amazon time, and they used that time to change course. They lost $567 million in 2001, but only $149 million in 2002and the last quarter was profitable. By 2003 they eked out a modest $35 million profit, which rose to $588 million in 2004. Wall Street was suffering from a massive Internet hangover, and Bezos provided the cure. A native e-commerce player that sold things for more money than it cost to obtain and deliver them. A concrete demonstration that the Internet was a real business platform.

The profits were not particularly largeJ.C. Penney reported a $1.3 billion operating profit in 2004 but they were real at a time when Wall Street wanted to see real profits.

As the years went by, Wall Street found itself enamored again with high tech. Googles emergence as a advertising juggernaut, the explosive growth of Facebook, and the enormous popularity of the iPhone all laid the groundwork for todays techno-enthusiasm. And Amazon quietly took advantage of that spirit of re-enchantment to stop worrying about profits. In the five years after 2004, Amazons profits nearly doubled to $902 million. But in the same period, total sales increased over 250 percent to $24.5 billion. These kinds of rapidly declining profit margins are the sort of thing a firm normally tries to avoid. But with a benign investor climate, Bezos could argue that growth is growth and margins are fundamentally irrelevant.

And that dream is the context for Amazons recent financial performance. Profits peaked in 2010 at $1.1 billionimpressive 28 percent growth from the previous year, but still a further diminution of profit margins in the context of 40 percent sales growth. Then profits fell 45 percent the next year even as sales grew 41 percent. Two years later, Amazons 2012 sales had nearly doubled to $61 billion from more than $30 billion, and yet the company posted its first loss since 2002. Investors were willing to believe in Jeff Bezos, so Bezos could afford to stop proving that he knows how to turn a profit.

In the early 2000s, Wall Street was suffering from a massive Internet hangover, and Amazon provided the cure.

Photo courtesy Jacob Bøtter/Flickr Creative Commons

Amazon is essentially the beneficiary of large Wall Street trends in its ability to eschew profits, yet its also bucking the trend among its peer technology giants. Microsoft is generally seen as ailing these days, but still generates billions in profits every quarter despite falling PC sales and substantial losses on initiatives such as Bing and Windows Phone. Googles 2012 net income of $10.7 billion exceeds all profits earned by Amazon ever. Apple earned $13.1 billion in net profit in its most recent quarter alone

The executives running these firms celebrate their high profits, but theyve become a subject of social concern. Enormous profits lead to enormous corporate income tax bills, bills that high tech companies seek to reduce through elaborate tax avoidance schemes. As exploiting these loopholes typically involves attributing income to foreign subsidiaries, firms end up with cash on their books that cant be officially brought back to the United States without taking a hit. That leads to the creation of new avoidance schemes through which incredibly wealthy firms take on debt to pay dividends and avoid the IRS. Beyond tax avoidance, high profits at a time of mass unemployment and stagnant wages strikes many as unseemly. And even mild-mannered business columnists like the Financial Times John Plender are beginning to ask why tech companies are hoarding so much money rather than investing it. He observes that seven big tech firmsApple, Microsoft, Google, Cisco, Oracle, Qualcomm and Facebookhave cash holdings that now top $340 billion, a near-fivefold increase since the start of the millennium.

Yet the hoarding turns the firms into targets. No doubt Steve Jobs believed the cash pile he was bequeathing to Tim Cook when he died was an enormous asset, on par with Apples strong brand and engineering talent. But without the companys charismatic founder on hand, its in some ways become a problem. Cook immediately set about trying to appease shareholders with a dividend and buyback program that soon grew more generous. This has only whetted the appetite of activist investors led by Carl Icahn to demand more money. Rather than saving for the future, Apples become a cash source for financial engineers. Google, for now, is still firmly in the hands of its founders, but nothing lasts forever. Microsoft has stumbled in recent years, and now activist investors are rumbling about trying to wrest control of the board of directors away from Bill Gates so the company can abandon the Steve Ballmer strategy of plowing Windows/Office profits into new ventures and instead become a piggybank.

For founders, executives, and technologists who care on some level about the fate of their companies and the idea of innovation, this is a depressing outcome. The geeks and engineers create the companies, but in the end they become pawns in the struggles of Wall Street. One thing that makes Amazon different is that Bezos, a veteran of hedge fund D.E. Shaw, is himself a finance guy rather than an engineer. Understanding Wall Street as he does, hes hit upon the ultimate way of avoiding the piggybank problemjust dont earn the profits that create the cash hoard in the first place. Invest the revenue instead.

To really understand this strategy as it applies to Amazon, you simply need to recognize that not every investmentin the sense of a future-oriented financial commitmentis an investment according to the rules of corporate accounting. If you take a bunch of money and use it to build a server farm or buy an office building, thats an accounting investment. Amazon does plenty of this kind of investment But what doesnt show up on the balance sheet in the same way is the companys most important investment: the firm commitment to ultra-low prices.

The goal of programs like Amazon Prime or Subscribe & Save is to get people to reorganize their lives around Amazon’s delivery infrastructure, not to make a quick buck.

Photo by Thinkstock

A simplistic pricing strategy looks like a parabola. The less you charge, the less money you make per unit sold, but the more units you sell. Plot all the different possible price points and you get a curve. The goal is to pick the price that puts you at the peak of the curve, maximizing your profits.

Amazons prices almost certainly arent set at this peak. Take Amazon Prime, the $79-a-year membership program that entitles you to free two-day shipping on most items. Would membership really drop 10 percent if the fee were raised to $87? It seems unlikely. In fact, Amazon has allowed inflation to slowly eat away at the real price of Amazon Prime while simultaneously sweetening the pot by adding a large suite of free streaming video and the Kindle Owners Lending Library to the deal. The price strategy isnt to maximize revenue or profit; its simply to maximize membership. The same strategy appears to underlie the pricing of Kindle and Kindle Fire hardware, which is sold at cost. The idea is to get Kindles into the hands of as many people as possible because Kindle owners will buy Amazon digital content. But this isnt a digital version of Gillettes strategy of offering customers cheap razors in order to sell high-margin bladesthe Kindle content is also cheap.* (Indeed, its so cheap that book publishers and Apple teamed up to create an illegal cartel to make the content more expensive .) The goal, rather, is to enmesh larger and larger groups of people more and more deeply in the habit of purchasing digital content and doing it through Amazons platform.

Prime members, by the same token, will rely on Amazon for more purchases. Indeed, Prime serves as a gateway into other Amazon discount programs. Subscribe & Save offers a 15 percent discount (20 percent with a real or fake baby ) to people who order regular deliveries of household goods or nonperishable groceries. Its extremely challenging to earn profits at these price points, but the goal is to get people to reorganize their lives around Amazons delivery infrastructure, not to make a quick buck.