After Buffett Should Berkshire Hathaway Be Broken Up

Post on: 19 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

There is an uncomfortable question hanging over one of the world’s biggest corporations: Should Berkshire Hathaway be broken up when Warren Buffett retires or dies? The answer might be found in the very underpinnings of how American industry is organized and governed.

Berkshire, of course, is the rare firm where the chief executive (Mr. Buffett, that is) is more famous than the company. Lately it has been the third- or fourth- most valuable company in the world, depending on what the stock market does on a given day. Its business is sprawling: Berkshire is an insurance company attached to an electrical utility attached to a railroad attached to a mutual fund attached to a private jet service attached to Dairy Queen.

It also is a standing repudiation of what academic economists thought they had figured out years ago about the pitfalls of conglomerates, those sprawling assemblages of disparate businesses that were all the rage in the 1960s and 1970s — Figgie International, ITT and Gulf and Western — and that corporate raiders spent the 1980s and 1990s dismantling.

It shouldn’t work, the academics would tell you. But it has. Essentially, it’s because Berkshire Hathaway is a corporate governance hack. It manages to combine a longer-term management philosophy with the practical benefits of being a publicly traded company in the modern age.

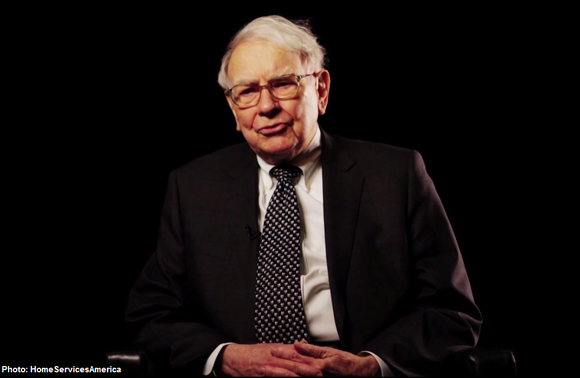

Photo

Warren Buffett after throwing a newspaper during a competition at a trade show at Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting in Omaha on Saturday. He has long run the company with a long-term view. Credit Rick Wilking/Reuters

So the question really is: Is the hack reproducible? At Berkshire’s annual meeting over the weekend, the debate pivoted off the fear that it is not. With Mr. Buffett now 83, and with Berkshire so large and sprawling that to buy its stock is in effect to buy a proxy for the American economy, had the time come for a reimagining of this enterprise? The Economist argued just that recently, writing that “given his irreplaceability and unrepeatability of his past dealmaking success,” Mr. Buffett should remind shareholders of conglomerates of the past that have unwound themselves, and he should tell them “that a gradual break-up will be his main recommendation to his successor.”

Warren Buffett, being Warren Buffett, did no such thing. He indicated a willingness to be even more acquisitive; he would even be open to a megadeal on the order of $50 billion. For context, here’s a sampling of the kinds of tiny companies worth about that much: Starbucks, Lockheed Martin and Costco.

So should Berkshire break up into smaller units? To get to an answer, you need to understand why conglomerates fell out of favor in the first place.

In the heyday of industrial conglomerates, companies like Gulf and Western, which Mr. Buffett specifically name-checked in response to a question this past weekend, would buy up a slew of smaller companies in largely unrelated industries. Each would continue operating under its new corporate parentage, continuing to make and sell widgets or gewgaws or whatever. The difference was that their profits would be funneled to the home office, with decisions on capital investments decided by their corporate overlords.

The theory, to the degree there was one, is that these wise allocators of capital in the home office would make better investment decisions than the managers on the ground possibly could, and that investors would love the diversification of owning shares in a company with lots of different business interests.

Later academic research cast major doubt on both theories. Whatever they might have gained in competitiveness from having hardheaded central office executives allocating capital, they lost in terms of nimbleness and ability to react to conditions on the ground. And it turns out, investors can just as easily get the benefits of diversification by buying shares of different companies; they don’t need well-compensated executives to build a conglomerate on their behalf. (Here, among others, is a paper by Philip G. Berger and Eli Ofek finding that combining firms into a diversified conglomerate reduces their value by 13 to 15 percent versus the result when remaining independent.)

Which bring us back to Berkshire Hathaway. In the popular mind, Mr. Buffett may be known best as a stock-picker, but the company’s investments in shares of other publicly traded companies added up to only 24 percent of Berkshire’s total assets at the end of March.

Most of Berkshire’s value is in the operating companies it owns, including giants like the auto insurer Geico, the utility MidAmerican Energy, the railroad BNSF and much smaller ones like See’s Candy and Acme Brick Co.

The companies have their own managers running them day-to-day. But in Omaha, this astonishingly large company, with 331,000 employees worldwide, has a corporate headquarters with a mere 25 people on a single floor of an office building. From there Mr. Buffett and his staff allocate capital and contemplate acquisitions or sales, hire or fire people to run those portfolio companies, and otherwise stay out of the way.

So is Berkshire Hathaway really any different from the inefficient conglomerates of old? Maybe. Here’s why:

Since the 1980s, American capitalism has veered toward a more concerted focus on maximizing value for shareholders. Any executive team that is hoarding cash or making potentially feckless investments is sure to come under fire from activist investors using all manner of tactics to get their way. (See, in one prominent recent example, Carl Icahn’s effort to persuade Apple to pay out more money to shareholders.)

At its best, shareholder activism can be a tool to replace irresponsible management. But there’s a good case that it is also making American executives think only about the short term. There is no reward for plowing money into an ambitious project that might take five years to pay off if Carl Icahn and other shareholder activists will be baying for your head after two. Why reinvest earnings into new products when all the external pressure is to pay the money out as dividends?

Mr. Buffett has an ironclad grip on the company — he owns 39 percent of Class A shares — and combined with a long-term approach, he can ignore the latest pleas by investors and shareholder activists. He can ignore the calls to invest in technology stocks in the 1990s, and ignore the calls to pay out dividends today.

He can invest opportunistically at times when no one else would, such as when Berkshire bought preferred shares of cash-hungry Goldman Sachs and General Electric during the darkest days of the 2008 financial crisis. And this sense that Berkshire will allow sound management for the longer term has led many owners of closely held private companies to sell to Mr. Buffett over the years, rather than auction their companies to the highest bidder.

In other words, because of Mr. Buffett’s reputation and enormous holdings of Berkshire stock, he can run the company with a long-term view even while benefiting from the wide ownership and liquidity that comes with having shares that trade on the New York Stock Exchange.

In the post-Buffett era, his conglomerate should remain one if you believe that the Berkshire corporate governance hack — of a long-term focus within a publicly traded company — is strong enough to survive him. Mr. Buffett’s strategy has always been to buy companies with a strong “economic moat” protecting them from competitors. Berkshire’s own economic moat is a history, management culture and corporate structure focused on the long term that can give it an edge over more short-term-focused public companies.

After he spent a lifetime building Berkshire Hathaway into a giant of American industry, Mr. Buffett’s final task may be an even harder one: to turn an advantage that has been tied together with his reputation and ownership of Berkshire stock into something that will outlive him.

The Upshot provides news, analysis and graphics about politics, policy and everyday life. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter .