Absolutely everything you need to know about the debt ceiling The Washington Post

Post on: 25 Май, 2015 No Comment

By Brad Plumer October 14, 2013 Follow @bradplumer

The federal government is still shut down. But there’s more mayhem to come: Congress has to deal with the debt ceiling. If lawmakers don’t vote to increase the nation’s borrowing limit by mid-October, the U.S. government won’t have enough money to pay all its bills.

Ben Franklin might have had thoughts on the debt ceiling, for all we know. (The Washington Post)

The debt-ceiling crisis could be the most serious one yet. The U.S. Treasury Department says that a failure to raise the borrowing limit could potentially trigger a debt default, which would lead to a financial crisis and recession that could echo the events of 2008 or worse.

Republicans in Congress say they don’t want a default. but many members also don’t want to approve any new borrowing until the Obama administration agrees to make certain policy concessions. It’s a standoff.

So it’s time to take a detailed look at what, exactly, the debt ceiling is, why we even have one, and whether apocalypse would really occur if Congress doesn’t lift it before Oct. 17.

What is the debt ceiling?

This isn’t the debt ceiling. But it’s not a terrible metaphor! (Washington Post)

When the federal government spends more than it takes in taxes — which it usually does — then the U.S. Treasury has to borrow the rest to pay all its bills. But Congress has always imposed a legal limit on how much money the Treasury can actually borrow from outsiders and other government accounts. That’s the debt ceiling.

The current debt limit is $16.699 trillion. The Treasury Department can borrow that much and not a penny more, unless Congress votes to raise the ceiling.

Note that the debt ceiling doesn’t determine how much the U.S. government is authorized to spend. Congress does that by setting the budget and passing various spending bills. The debt ceiling only determines whether the U.S. government can borrow enough money to pay for programs that Congress has already enacted, like Medicare reimbursements or military pay.

So when will the government hit the debt ceiling?

Technically, we’ve already reached the borrowing limit. But the government won’t actually run out of money to pay its bills until some time after Oct. 17.

The U.S. government hit its $16.699 trillion borrowing limit back on May 19 . Since then, the Treasury Department has taken a slew of “extraordinary measures” — such as tapping exchange-rate funds — to raise an extra $412 billion and ensure the government has enough money to meet all its obligations, like paying bondholders and sending out Social Security checks.

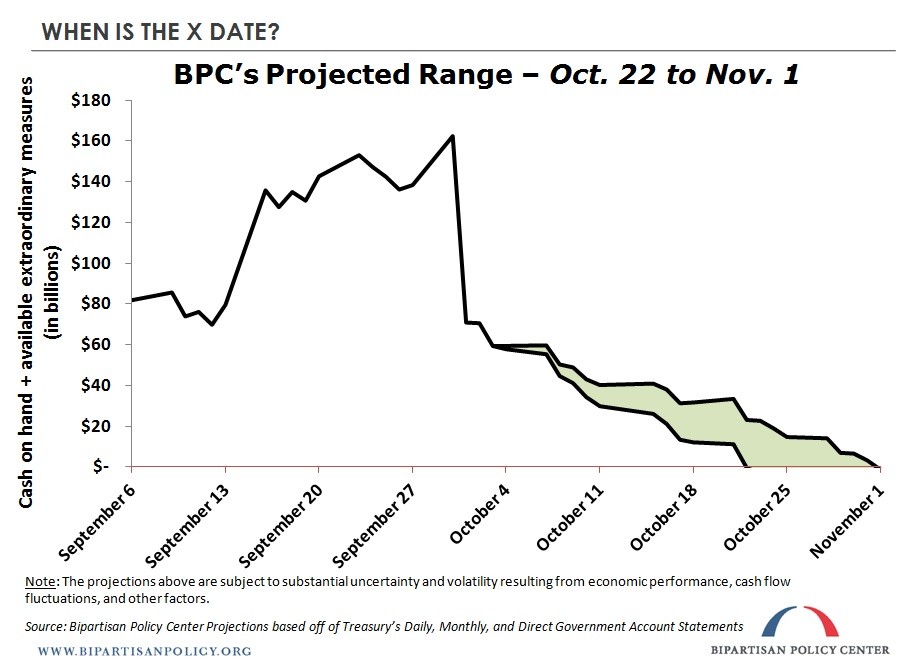

By Oct. 17, however, the Treasury Department will run out of extraordinary measures. At that point, the government will be running low on cash, and it won’t be able to borrow or scrounge up any more money.

We estimate that, at [Oct. 17], Treasury would have only approximately $30 billion to meet our country’s commitments, said Treasury Secretary Jack Lew in a Sept. 25 letter to Congress. This amount would be far short of net expenditures on certain days, which can be as high as $60 billion.

So what happens on Oct. 17? Is that doomsday?

It’s hard to say. At some point after Oct. 17, the federal government will only bring in enough tax revenue to pay about 68 percent of its bills for the coming month, according to an analysis by the Bipartisan Policy Center. (More precisely, the government will bring in roughly $222 billion in taxes and owe roughly $328 billion between Oct. 18 and Nov. 15.)

The first missed payment won’t necessarily happen right on Oct. 17, but it would likely happen soon thereafter. The government typically spends a few billion dollars per day on various items. And it will also face these large outlays in the coming weeks:

Many analysts think that Nov. 1 is the real doomsday date. It’s unlikely the government will be able to make that $58 billion payment for Social Security, Medicare, military pay, and other benefits without being able to borrow more money.

Hold on. The government is shut down. Does that push back the doomsday date?

These closed parks won’t help much. (The Washington Post)

The shutdown only changes the situation a bit. If the government is closed, that reduces the number of daily payments Treasury needs to make. But even during the shutdown, the U.S. government is still required to make all sorts of other payments, including Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the debt. And those are the big-ticket items.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs have estimated that even with a week-long shutdown, Treasury would still likely exhaust its cash balance by the end of October, when that $58 billion in benefit payments comes due.

So what happens when the government doesn’t have money to pay its bills?

Yikes. (Wikipedia)

The most straightforward scenario is that the government’s computer systems would keep making payments until its checks started bouncing. And its hard to predict in advance who would get stiffed.

Each and every day, computers at the Treasury Department receive more than 2 million invoices from various agencies. The Department of Homeland Security might say, for example, that it owes a contractor $1 million for new border security technology. The Treasury computers make sure the figures are correct and then authorizes the payment. This is all done automatically, dozens of times per second.

According to the Treasury Department’s inspector general, the computers are designed to make each payment in the order it comes due. So if the money isn’t there, the defaults could be random. Maybe a payment to a defense contractor comes up short. Maybe a Social Security check bounces. Maybe an interest payment to bondholders fails. No one knows.

Does it matter if the government misses a few bills?

Freak out! (The Washington Post)

Probably. A defense contractor might accept an IOU. A retiree who sees his Social Security check delayed might be less pleased. But the financial markets could be really unforgiving.

Many economists think it would be disastrous if the government ever missed an interest payment on the debt, like the ones due on Oct. 31 and Nov. 15. The global financial markets are structured around the notion that U.S. Treasuries are the safest asset in the world. If that assumption were ever called into question, havoc could ensue.

It would be like the financial market equivalent of that Hieronymus Bosch painting of hell , Michael Feroli, chief economist at JP Morgan, told me earlier this year.

That sounds bad. Can’t the government just pay the important bills and delay the rest?

Hard to teach old computers new tricks. (ALAMY)

That’s somewhat doubtful. This idea is known as prioritization, and it’s been floated before. During the last debt-ceiling fight in 2011, Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Penn.) suggested that the government should focus on paying bondholders and the military and retirees and delay the rest.

The problem is that prioritization on the fly may be logistically infeasible, argue Shai Akabas and Brian Collins of the Bipartisan Policy Center in a recent report. It would involve sorting and choosing from nearly 100 million monthly payments, they write. It’s difficult to stop paying the Education Department while making sure Social Security checks keep flowing.

That view is shared by Mark Patterson, a former chief of staff at Treasury: The U.S. government’s payment system is sprawling, he explained. It involves multiple agencies. It involves multiple interacting computer systems. And all of them are designed for only one thing: To pay all bills on time. The technological challenge of trying to adapt that to some other system would be very daunting, and I suspect that if we were forced into a mode like that the results would be riddled with all kinds of errors.

Now, Congress could always pass a bill to reconfigure Treasury’s payment systems. But this hasn’t happened yet, and it’s unlikely that a massive overhaul will happen between now and Oct. 17.

Aren’t debt payments made through a separate system? Can’t they be prioritized?

20Canine%20Cash.JPEG-05b45.jpg /%

This dog got paid by the U.S. Treasury. Will you? (The Independent Record, Eliza Wiley/Associated Press)

That’s technically true. The computer system that handles U.S. sovereign debt payments, Fedwire. is separate from the system overseeing payments to government agencies and other vendors. That raises the question of whether Treasury could stop all other payments and only pay bondholders, to avert a financial crisis. Indeed, many market observers suspect this is exactly what would happen.

There are two problems here. First, it’s unclear whether Treasury has the legal authority to do this — the agency has never dealt with this situation before. Anyone who says they know for sure whether this is legal is not telling the truth, Steve Bell of the Bipartisan Policy Center told me. (See pages 8 and 9 of this Congressional Research Service report for more on this.)

Those legal questions could, in theory, be cleared up: Back in 2011, Toomey introduced a bill that would require Treasury to prioritize bondholders above everyone else. But that bill never passed Congress.

Second problem: If Treasury only paid bondholders, that might require stopping or delaying a variety of other payments that the government makes in order to hoard cash. Stop paying Social Security. Stop paying Medicare. That might avert a financial crisis, but it would roil the U.S. economy — Goldman Sachs thinks the resulting drop in spending could trigger a recession.

The Obama administration, for its part, maintains that it can’t and shouldn’t prioritize payments. Any plan to prioritize some payments over others is simply default by another name, Lew wrote in his letter to Congress. There is no way of knowing the damage any prioritization plan would have on our economy and financial markets.

(Here’s a much longer post on the whole question of prioritization.)

What would be the economic consequences of crashing into the debt ceiling?

A scene from Hieronymous Bosch’s famous painting, The Breaching of the Debt Ceiling (Wikipedia)

Nothing good. A prolonged crisis could hurt economic growth significantly. And a default on the debt would almost certainly create big disruptions in the financial markets.

Remember, if Congress refuses to lift the debt ceiling, the federal government can only pay out as much as it takes in taxes. Overall payments would drop by 32 percent over the coming month. Goldman Sachs, for its part, estimates that these spending cuts would come to about 4.2 percent of GDP — a much sharper drop than, say, the sequestration budget cuts or the furloughs caused by the government shutdown.

The financial response is harder to forecast, especially if prioritization is impossible. The Treasury Department certainly thinks the prospect of missing a debt payment could be ruinous: Credit markets could freeze, the value of the dollar could plummet, U.S. interest rates could skyrocket, the negative spillovers could reverberate around the world, and there might be a financial crisis and recession that could echo the events of 2008 or worse.

Other analysts agree. Take Fedwire, the central clearing system that banks in America use to move cash, bonds, and other financial assets around. This system shuffles around trillions of dollars a day. But as a recent note by RBC Capital Markets notes, Fedwire isn’t set up to handle defaulted securities. The entire system would freeze. Let us be perfectly clear, the note says, crossing the debt ceiling would be catastrophic.

A recent note by Deutsche Bank analyst David Bianco estimated that the U.S. stock market could lose 10 percent of its value if the government had to prioritize payments — and 45 percent of its value if the U.S. government actually missed an interest payment:

(For more on other potential financial consequences of a default, most of them bad, see this post by Kevin Roose.)

Has the United States ever defaulted on its debt before?

Shakedown, 1979.

Sort of. Back in 1979, Congress waited until the last minute to raise the debt ceiling, and the government inadvertently defaulted on about $122 million worth of Treasury bills, due to unexpectedly high demand and an error in word-processing equipment. This was only temporary, and Treasury quickly corrected the error.

Still, the damage was long-lasting. A 1989 study in the Financial Review estimated that the incident raised the nation’s borrowing costs by about 0.6 percent, or $12 billion. And the damage lasted for months. That was after a brief, accidental default that was corrected quickly. A debt-ceiling crisis today would almost certainly be far more consequential.

(Technically, the United States also defaulted on some war debts in the late 18th century, thanks to a plan drawn up by Alexander Hamilton. And when Franklin Roosevelt ended the gold standard in 1933, that was a default of sorts. But those aren’t great analogues.)

Come on. Surely the Obama administration can do something to avoid financial Armageddon. Right?

Dudes, don’t look at me. This ceiling is unstoppable. (AP)

Well. there are a few other possibilities if we blow past the debt ceiling. Some are impractical. Others, like the platinum coin option, sound ludicrous. But it’s also a bit moot: The Obama administration has explicitly ruled them all out.

First, Treasury could try to buy time by delaying payments — agency officials deemed this the least-bad approach back in 2011. If Treasury was facing $10 billion in obligations on Monday, but only $7 billion in revenue came in, the agency could wait until it had the full $10 billion on hand before paying Monday’s bills in full. The problem is that during the delay, Tuesday’s bills are piling up. Then Wednesday’s. This tactic would quickly become unsustainable.

Alternatively, the Obama administration could try simply ignoring the debt ceiling. Last fall, two legal scholars, Neil Buchanan and Michael Dorf, wrote a paper arguing that Obama would be caught in a constitutional dilemma come Oct. 17. Congress has required that the president spend money on certain programs, but they’ve also mandated that he can’t borrow any more to pay for it.

The least bad constitutional option, say Buchanan and Dorf, would be for Obama to ignore the debt ceiling and unilaterally issue new bonds. The problem is that this would be legally questionable, and lenders might be wary of buying new U.S. government debt — creating more market panic.

What about the 14th amendment option? Or the platinum coin option.

Don’t laugh. (AP)

Some law professors and Democrats have suggested that Obama can declare the ceiling unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment, which says The validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned.”

Still others have suggested that Obama could mint a $2 trillion platinum coin to fund the government. In theory, this is plausible: Thanks to an odd loophole in the law governing commemorative coins, the U.S. Treasury is technically allowed to mint as many coins made of platinum as it wants and can assign them whatever value it pleases.

The problem with these schemes? For one, they’d obviously be unorthodox and contentious. They could cause a political uproar and possibly market panic. But more to the point, administration officials have explicitly ruled them out . Lew has said there are only two ways the debt ceiling fight can go: Either Congress lifts the debt ceiling, or the U.S. government will default on some of its payments.

Fine. How much does the debt ceiling need to be raised by to avoid chaos?

The Bipartisan Policy Center report estimates that Congress would need to raise the debt ceiling by around $1.1 trillion to allow the government to meet all of its obligations through the end of 2014.

Has Congress ever raised the debt ceiling before?

Yes. All the time, although members of Congress have always complained loudly about doing it. (When he was a senator in 2006, Barack Obama voted against raising the debt ceiling. although he later said this was a mistake.)

What’s more, sometimes lawmakers have attached conditions to bills that raise the debt ceiling. In 1980, Congress raised the nation’s borrowing limit and eliminated a fee on oil imports in the same piece of legislation .

But when push comes to shove, the House and Senate have always found a majority of votes willing to raise the debt ceiling before calamity strikes:

So why has the debt ceiling been so contentious lately?

It all started back in 2010. Republicans had just won a huge victory in the midterms, and Congress agreed during the lame-duck session to extend $850 billion worth of tax cuts. But Democrats, who still ran Congress at the time, didn’t include a debt-ceiling hike in the deal. Harry Reid’s attitude at the time was, Let the Republicans have some buy-in on the debt. They’re going to have a majority in the House.”

So, in 2011, when it came time to raise the debt ceiling, Republicans refused to do so unless they received significant spending cuts in return. That fight dragged on for much of the summer of 2011, and the financial markets got jittery .

Eventually, Republicans and the White House struck a deal. Congress would raise the debt ceiling by $2.1 trillion (to its current level). At the same time, lawmakers would enact $2.1 trillion in deficit reduction — a deal that eventually led to the sequestration budget cuts.

What do Republicans want this time around?

I could’ve sworn I put those demands somewhere. Lemme see. House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio). (Scott Applewhite/AP)

The demands have shifted over time. The original bill from House Republicans to raise the debt ceiling included a whole batch of policy proposals, from a delay of Obamacare to curbing the Environmental Protection Agency to fast-tracking the Keystone XL pipeline. Democrats rejected all of those conditions and asked for a clean bill that solely hikes the debt ceiling.

Lately, House Republicans have floated a plan that would extend the debt ceiling until February 7, reopen the government until January 15, suspend Obamacare’s medical-device tax for two years, and require income verification for Obamacare enrollees. This differs slightly from a Senate plan to extend the debt ceiling, and it’s still unclear how the two chambers will resolve their differences.

At the same time, aides to House Majority Leader John Boehner (R-Ohio) have previously told reporters that they won’t let the country default. If worse comes to worst, they say, Boehner will pull together Democratic votes to pass a clean debt-ceiling hike. So we’ll see what happens.

What’s even the point of a debt ceiling then? Should we abolish it?

Experts are mystified by how New Zealand manages to survive without a debt ceiling. (Dunedin NZ via Flickr)

Good question! Back when the debt ceiling was first adopted in 1917, it was arguably a useful device for Congress to prevent the president from spending however much he wanted. But since 1974, Congress has created a formal budget process to control spending levels.

As such, many observers don’t see why there’s a need for Congress to authorize borrowing for spending that Congress has already approved — especially when a failure to lift the debt ceiling would be so devastating. Indeed, between 1979 and 1995, the House simply lifted the debt ceiling automatically as soon as it approved a budget (a process known as the Gephardt rule).

It’s also worth noting that most modern democracies seem to do just fine without explicit borrowing limits, including Britain, Canada, Germany, Australia, and France. (One big exception here is Denmark, though its debt ceiling always gets raised without incident.)

For what it’s worth, here’s a long list of experts who think the United States should just abolish its debt ceiling altogether. In a January survey of academic economists by the University of Chicago, 84 percent agreed that having a debt ceiling creates unneeded uncertainty and can potentially lead to worse financial outcomes.” But no one listened to them, so here we are.

Further reading: