A Primer On Investing In The Tech Industry_1

Post on: 6 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

What is venture capital?

Venture capital is capital invested or available for investment in the ownership element of a new enterprise. While there may also exist a preferred return or debt component, the defining characteristic is that the capital investor retains some equity in the venture.

1. Seed

5. Mezzanine

6. Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Seed money, seed capital or seed financing is venture capital used to finance the early development of a new product or service concept. Generally, it is usually the most expensive in terms of equity concessions since there is no guarantee that the product or service under development will ever make it to the stage of a workable prototype much less a viable commercial enterprise.

Start-up capital usually refers to venture funding sufficient to generate initial sales and profits. Our view is that if an initial private placement, distributed on the basis of a viable three-to-five-year plan to reach fundamentals sufficient to undertake a successful public offering, is fully subscribed, there should be no need for second and third-stage equity offerings. This is advantageous to both the founders, management team and first-stage investors in that neither suffer any subsequent dilution prior to the firm’s initial public offering (IPO).

In the event that the firm’s initial private offering does not prove sufficient, the company may need to resort to additional debt or equity placements to raise more capital. This may become necessary due to management’s failure to utilize properly its initial financial resources or it may result from unforeseen changes in the company’s operating environment or from many other factors. If a follow-on-stage offering is used to fund an expansion that enables a company to later conduct a public offering, it is sometimes referred to as a mezzanine financing. In all later-stage financings you can be sure of one thing, management’s equity will almost certainly be reduced, drastically so in many cases. We’ve seen common share cram downs as bad as 60-to-one.

The probabilities that later-stage private offerings will be necessary can be reduced by stating your total funding requirements up front and raising adequate reserve capital. Properly presented, investors should prefer this approach because it charts the most direct course towards the twin goals of profitability and liquidity.

We don’t believe so. We feel it is important to have a well-thought-out three-to-five-year financial plan and to balance the need for contingent reserves against the need to provide adequate return on investment. We believe that most investors want to see that management has both (i) requested sufficient capital to create a viable enterprise capable of effecting a successful IPO within a reasonable time frame and (ii) has a plan to utilize such capital in an efficient, cost-effective manner. Therefore, we believe it is wise to base a new venture’s financial projections and private offering plan on adequate and substantial, but not excessive, capital reserves.

IPO is the frequently-used abbreviation for initial public offering. Many venture investors think of it as payday. That’s because, if successful, an initial public offering will create a viable market for the company’s stock and provide its founders and early-stage investors with a cash return on their investment and, eventually, liquidity for their remaining shares.

Further, since liquidity is an intrinsically valuable investment component, the market will usually assign it some level of premium. At least part of a publicly-traded company’s market cap can be thought of as a liquidity premium as investors will pay more for a security which can be quickly and easily converted into cash than for an investment which offers a similar risk/reward profile but will require time and effort to liquidate.

In the past few years, the IPO market has fluctuated between irrationally euphoric and virtually non-existent. Fortunately, since it is impossible to predict market conditions for more than a few months out, venture capitalists generally do not factor in the current state of the IPO market when considering new investments in start-ups.

It is very hard to invest in anticipation of a market cycle. The companies we fund now are going to be going public two, three, four, five years from now. We have no idea what the [IPO] markets are going to be like at that point, so we might as well not worry about it,

says Robert Nelson, Co-Founder and Managing Director of ARCH Venture Partners.

A price/earnings ratio, or P:E, is a mathematical articulation of the relationship of a company’s earnings to its market capitalization as expressed as a fraction with the current share price as the numerator and the current after-tax earnings per share as the denominator.

For example, a company with a total of 10 million shares issued and outstanding, after-tax earnings of $5 million and currently trading for $6.00 a share would be said to have a price/earnings ratio (or multiple) of twelve-to-one (or simply 12). Notice if you multiply your earnings per share ($0.50) by 12 you get $6.00.

It’s important to realize that a stock’s P:E is not arbitrary; the board can’t declare it. The price/earnings ratio is determined by the market and is influenced by many factors including investors’ expectations of future earnings, the company’s book value and other fundamentals and all those factors which affect the public securities markets as a whole such as interest rates, inflation, unemployment, Federal Reserve policy, etc.

It is the potential for a private company to attain sufficient fundamentals to allow for a successful public offering, and, hence, a much higher price/earnings ratio (than for a privately-held firm), which provides a return attractive enough to warrant the risk usually associated with venture capital investing. And to a certain extent, industries which historically command higher price/earnings ratios should, on margin, be more attractive to astute venture investors.

Shares issued under private offering exemptions are subject to restrictions on transfer imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 144. Such stock is often referred to as legend stock, restricted securities or 144 stock and may not be sold immediately following the firm’s IPO. This protects IPO investors from a drastic drop in share price due to a sudden increase in supply and allows for the development of a healthy aftermarket.

There is a simple and fair way for founders and early investors to cash in at least some of their holdings and this involves the registration of a portion of their shares (and the sale thereof) in the firm’s initial public offering. As long as management continues to retain most of their holdings, the company’s underwriters (brokerage firms contracted to market the company’s stock to the public) and IPO investors will generally not view this as a bail out. Many entrepreneurial companies allow early-stage investors, and even founders, to register (and sell off) up to about 20 percent of their holdings in the IPO. Further, after one year, the SEC will generally allow limited sales of restricted securities and unlimited sales after two years.

Note: This is not intended as a complete discussion of Rule 144 but is given to demonstrate one method investors and founders may use to cash out.

If management seeks to sell too many of its shares in the IPO, the company’s underwriters may balk. Naturally, they will be concerned that investors will shy away from the offering, interpreting this sell off as an indication that management is not thrilled by the company’s future prospects. The underwriters may demand other concessions (such as higher discounts) or they may conclude that the offering is not viable. Provided that the IPO is not premature, that is, it is based on sound economic fundamentals, a balance can usually be struck — and a do-able deal negotiated — which satisfies underwriters and IPO investors, results in a favorable market capitalization, a solid aftermarket and also puts significant cash into the pockets of the founders, managers and early-stage investors.

Venture investors include:

1. Institutional venture capital funds typically organized as limited partnerships.

2. Corporations seeking to gain access to new technologies and/or markets.

3. Corporations seeking venture opportunities strictly to enhance return on equity.

4. Wealthy individuals who either specialize or have a percentage of their portfolio in venture capital investments.

5. Entrepreneurial business owners and corporate managers.

Says John H. Martinson, president of the National Venture Capital Association,

The success of the venture industry is now attracting record amounts of growth capital from other sources such as corporate venturing programs. This expands the sources of growth funding available for entrepreneurs.

While all venture investors can be assumed to fancy a profitable opportunity, secondary motivational factors, as well as corporate cultures, vary amongst the groups cited above. To quote Prime Computer founder and prominent venture investor John Poduska,

I do angel deals for some of the same reasons I support the ballet. Take one look at me and you’ll know I’m not a ballet dancer, but I like being part of something that’s worthwhile.

On the other hand Corporate Venturing News reports that,

Over 80 percent of corporate venture capital groups are investing primarily for strategic return.

Hence, the strategies taken with respect to soliciting financial assistance from various investors may differ significantly. Part of what contributes to a successful private offering is the credibility gained by approaching prospective investors in a fashion with which they are comfortable and most likely to interpret as professional.

Through industry analysis, research, personal contact and experience, Venture-Net has developed a proprietary database of active, pre-qualified, accredited venture capital investors. These include both private and institutional investors who are interested in financing start-up ventures. Some may specialize in a particular area such as medical or high-tech ventures. Others may be open to virtually any promising opportunity.

The common denominators are:

1. They have or control substantial financial resources liquid and available for venture capital investments.

2. They actively investigate, review and invest in start-up ventures; they are not merely LBO funds masquerading as venture capitalists.

3. They have an established business relationship with Venture-Net Partners, its general partner, or other affiliate, sufficient to determine that they are sophisticated and qualified investors interested in exploring various types of venture opportunities.

Yes, there are both state and federal securities laws regulating many aspects of private offerings which specify both civil and criminal sanctions for violators. Further, these laws vary from state to state and many statutes are subject to fairly complex legal interpretations. Potential problem areas include: prohibitions on general solicitation and public advertising; investor suitability and sophistication standards; sufficiency of previously-established business relationships; and form, accuracy and completeness of investment-inducing disclosures.

Federal law requires that an offering of securities be registered unless a specific exemption from registration is available. If no such exemption is available, a company seeking to offer its securities for sale must first register them with the Securities and Exchange Commission pursuant to the Securities Act of 1933. Such an issuer must complete a specified registration statement (such as a Form S-1) and obtain SEC clearance on its adequacy before offering its securities. The company must also satisfy the securities regulations (blue sky laws) of each and every state in which it intends to offer its securities.

Fortunately, both federal and most state’s securities laws provide exemptions from registration in specified circumstances. It is important to note, however, that a securities offering is never exempt from the anti-fraud provisions of the 1933 Act. Further, exemption from federal registration does not necessarily result in a corresponding state exemption nor is an exemption obtained in one state necessarily available in every state in which an issuer may wish to offer and sell its securities.

Though often thought of as a mini-public offering, private offerings differ from registered public offerings in the following ways:

1. Private offerings are generally less time-consuming and expensive in terms of legal, accounting, development and offering costs.

2. Disclosure requirements vary but are generally less extensive for a private offering.

3. Reporting requirements under the 1933 Act and certain other obligations of public companies are not triggered under a private offering.

4. Limits are imposed on the number and qualifications of investors allowed to purchase privately-placed shares and, in certain instances, on the amount which may be raised.

5. Market capitalizations will generally be less for a private offering due to constraints on the number of purchasers and restrictions on resales.

6. The publicity that results from a public offering, and the public image that accrues to a reporting company, will not be obtained in a private offering.

Today, the most commonly-used exemptions from federal registration requirements are the private placement and limited offering exemptions provided by the 1933 Act as modified by the Small Business Investment Incentive Act of 1980 and SEC Regulation D adopted on March 3, 1982.

According to SEC Release No. 6389, at 84,907, Regulation D is designed to simplify and clarify existing exemptions, to expand their availability, and to achieve uniformity between federal and state exemptions in order to facilitate capital formation consistent with the protection of investors.

Regulation D consists of six Rules, i.e. 501 through 506, which became effective on April 15, 1982 and two, 507 and 508, which became effective April 19, 1989. These rules set forth the conditions attached to Regulation D exemptions. Rules 501 through 503 define the uniform terms and conditions; Rules 504 through 506 describe the three specific transactional exemptions; and Rules 507 and 508 modify the previous Rules and address the consequences of an issuer’s failure to comply with the terms, conditions and requirements of Regulation D.

The most commonly-used exemptions from registration in the state of California are provided under Corporations Code Sections 25102(f) and 25102(h). In general, such offerings are restricted to an unlimited number of excluded, and a maximum of 35 non-excluded, investors who must be, nonetheless, sophisticated enough to evaluate the merits of the offering as well as financially-able to risk the loss of their entire investment.

Such prospective investors may not be contacted via public advertisement or general solicitations and must receive disclosure documents sufficient to satisfy the anti-fraud provisions of the 1933 Act. An application for permit under 25102(n) requires further restrictions on investor qualifications but allows for certain types of advertisements which would otherwise be illegal.

Employment of experienced securities counsel is an essential prerequisite to the successful placement of a private offering of equity securities; however, prior registration with the SEC is not always necessary in order to raise capital.

Note: This is not intended as a thorough or sufficient discussion of all aspects of securities law as related to limited offerings and private placements.

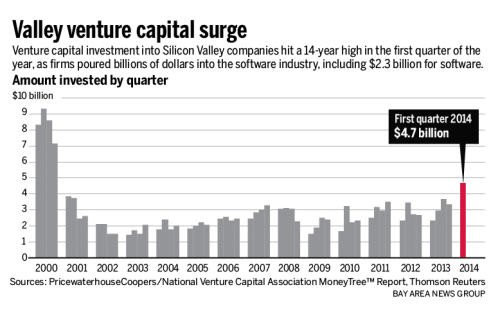

During a six year run beginning with 1995, the venture capital industry witnessed an unprecedented expansion of resources and activity with a record of over $105 billion invested in 2000. From the second quarter of 2000 to the first quarter of 2003, the trend was negative but the total amount invested still exceeded $100 billion over the down years of 2001 through 2004.

Total Annual U.S. Venture Fund Investments