Zerocoupon bond_1

Post on: 8 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

What in the world is a zero-coupon bond?

By Dorothy Rosen • Bankrate.com

Hearing the finer points of bonds explained leaves you feeling like you’re listening to a foreign language. No matter how many times you get it pounded into your head that a bond’s yield moves in the opposite direction of its price, you still find your eyes glazing over and your head starting to nod.

So the concept of the zero-coupon bond is going to be a real snooze, right? Well, I can’t promise to turn bond investing into John Woo directing Jackie Chan, but I can give you a pretty clear idea of what you’re getting into when you step up to the plate with one of these securities.

First, some definitions might be useful. A bond is essentially an IOU sold by governments and companies to investors that guarantees that borrowers will repay borrowed money to the lenders, at certain interest rates by a certain time.

A coupon is the interest an investor receives on bonds he or she owns — a check arrives every six months until the bond’s principle is due. Back in the dark ages, bonds actually used to come with small, detachable coupons that bondholders would physically redeem to receive the interest they were owed. Today, bond interest is usually paid through electronic transfer, but the anachronistic term persists.

Two other useful definitions are face value, which is the value of the bond at the time it’s redeemed, and maturity date, which is the date at which you are able to redeem your bond for cash at face value.

For example, if a bond with a $1,000 face value matures on Dec. 31, 2000, you will receive $1,000 on that date. It doesn’t matter if interest rates are up or if the Dow and Nasdaq are in the toilet. Unless the borrower defaults, the investor will receive the face value of her bond on its maturity date.

- advertisement -

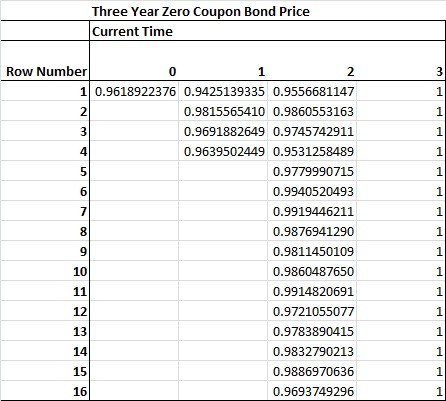

A zero-coupon bond is a bond that is bought at a deep discount from its face value. It pays zero annual interest during its life, but pays full face value on its maturity date. If you buy a $10,000 zero-coupon bond for $5,000, you are buying it at a deep discount. The discount — in this case $5,000 — is actually the interest that will accumulate during the life of the bond. Most people buy zeros issued by the U.S. Government or state and local municipalities.

Some investors favor the zero because it provides the comfort of a secure investment. If you buy a non-callable zero — one that the issuer cannot make you redeem before its maturity date — you effectively have a sure thing if you hold the bond to maturity.

If you need $10,000 in three years for school tuition, or $30,000 in seven years to pay off a mortgage, the non-callable zero will get you there. But to achieve this comfort level, you need to be sure you’re not going to have to cash it in before its maturity date, because that would mean selling it on the open market in competition with newer bonds that may be cheaper.

If interest rates have climbed since you bought it, then the interest offered on a new bond will be more than $5,000, which drops the purchase price of your bond below the amount you paid. If you sell your bond, you may lose money.

Tax wise, if you buy municipal zeros, you’re spared the federal tax that is levied on Treasuries for each year’s imputed interest.

Investors who buy Treasury zeros often get around the tax disadvantage by putting them in tax-deferred retirement accounts, like an IRA, or the kids’ accounts, if the children are in a low-to-no income tax bracket.

DOROTHY ROSEN has a master’s degree in finance, with a specialization in accounting, from the Kellogg Graduate School at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. Rosen has more than 15 years of experience in the financial arena, serving in Illinois and Florida as a certified public accountant, financial consultant, expert witness and educator. She is owner of Dorothy Rosen, CPA, a public accounting firm that serves individuals and small businesses.