Why the Asset Turnover Ratio Matters

Post on: 23 Май, 2016 No Comment

- Page Title:

- Page URL:

This page has been successfully added into your Bookmark.

Follow

Someone who reads my blog sent me this email:

Geoff,

I have a question about something you wrote a while ago. You turned it into the article Warren Buffett: A Return on Capital Investor .

You wrote:In the Mid-Continent Tab Card Company example. Buffett is saying what is sales/assets and what’s the profit margin. If the profit margin gets cut in half, I’ve still got sufficient asset turnover on the lower profit margin to have an acceptable return on my own investment in years 2 and 3.

I’m not sure I understand this. Is the sales to assets ratio simply sales volume?

When I watched the video, I thought Buffett’s point was that the margins were not sustainable. Potential competitors were going to see the (return on capital) and the low barriers to entry and enter the field to compete with Mid-Continent. Buffett was merely asking, if the inevitable competition arises and profit margins get squeezed, can I still hit my hurdle rate of 15%?

Is it this correct? If so, what are you getting at in your second sentence above?

I’m also not sure I understand what you mean by a company leveraging its equity. Can you explain?

Thanks as always,

Andy What you’re saying is very close to being right. But, you’re skipping part of the basic business equation when you say:

Potential competitors were going to see the (return on capital) and the low barriers to entry and enter the field to compete with Mid-Continent. Buffett was merely asking, if the inevitable competition arises and profit margins get squeezed, can I still hit my hurdle rate of 15%? No. Buffett wasn’t merely asking about profit margins. He was asking about profit margins given a certain level of asset use.

He knew how much assets the business had. What he needed to know was how much use they’d get out of those assets in terms of the sales volume the assets could produce and then also how much of that sales volume the company got to keep as profit.Here’s the key quote about asset turnover from Alice Schroeder’s explanation of Warren Buffett ’s investment in Mid Continent Tab Card Company:

So he asks them the numbers. And they explain to him that they are turning their capital over 7 times a year. A…press costs $78,000. Every time they run a set of cards through and turn their capital over they are making over $11,000. So, basically, their gross profit a year on a press is enough to buy another…press. At this point Warren is very interested. Their net profit margins are 40%. It’s like the most profitable business he’s ever had the opportunity to invest in. The 15% hurdle rate is a return on his investment. Buffett’s return on his investment depends on the business’s return on capital.

Not the business’s profit margin.

The profit margin is only part of the return on equity equation. Saying a good profit margin means a good return on capital is like saying a good cook means a good meal. No. A good cook plus good ingredients plus a good recipe means a good meal.

Likewise, a good return on equity depends not just on wide profit margins but on wide profit margins, heavy asset use, and appropriate financial leverage.

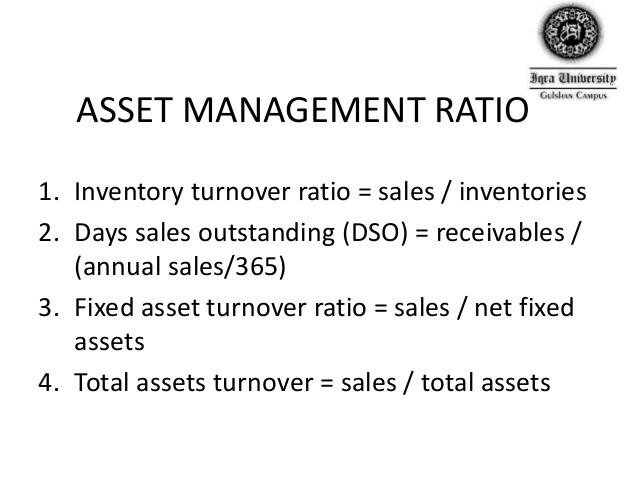

Asset turnover is Sales/Assets. See my article DuPont Analysis for Value Investors for details.

The DuPont analysis article is important because it deals with something I don’t see investors talk much about – the asset turnover ratio.

A DuPont analysis is basically just a way of breaking down a company’s return on equity into the key components a business can control. It’s a decomposition of return on equity. It just breaks the whole down into smaller pieces. But it’s very useful, because it identifies the key metrics a business has to execute on to achieve a high return on equity.

It also throws cold water on predictions that aren’t based on at least somewhat realistic ratios. A DuPont analysis is a much better tool than just doing an earnings projection based on past performance and expected future unit volume.

A DuPont analysis shows you what a company does well, what it does badly, and what – maybe, just maybe – it can do better to goose its return on equity.

Here’s what a DuPont analysis looks like:

Profit Margin = Profit/Sales

Asset Turnover = Sales/Assets

Financial Leverage = Assets/Equity

And.

Return on Assets = Profit Margin * Asset Turnover

Return on Equity = Return on Assets * Financial Leverage

In other words.

(Profit/Sales) * (Sales/Assets) * (Assets/Equity) = Return on Equity

When you’re looking at free cash flow, it makes sense to add a fourth ratio – which is free cash flow divided by net income.

So.

(Net Income/Sales) * (Sales/Assets) * (Assets/Equity) * (Free Cash Flow/Net Income) = Cash Return on Equity

A lot of investors talk about profit margins. And there’s no doubt profit margins matter. But, the truth is that all 4 of these ratios matter. Profit margins, asset turnover, financial leverage, and cash conversion all matter. And improving any of those 4 ratios can improve business performance and ultimately stock performance.

Now, some of these ratios are severely constrained by the type of business you’re in. Railroads have a very hard time turning their assets quickly. The same is true of cruise lines.

Generally, it takes a lot of assets to produce a small amount of sales at a railroad or a cruise line. For every $1 of assets they may have only 40 cents of sales. That is such a serious weakness that railroads and cruise lines tend to have very low returns on equity even when they have very high profit margins. The reason for that is simple math. Yes, they are keeping a lot of each dollar of sales in profits. But return on equity doesn’t require high net income in relation to sales. Return on equity requires high net income in relation to equity.

That means profit margins only matter when you look at them with asset turnover.

My point about asset turnover — and Alice Schroeder even says this in the video — is that Buffett looked at how quickly Mid Continent Tab Card Company was turning their capital:

So he asks them the numbers. And they explain to him that they are turning their capital over 7 times a year. A…press costs $78,000. Every time they run a set of cards through and turn their capital over they are making over $11,000. So, basically, their gross profit a year on a press is enough to buy another…press. At this point Warren is very interested. Their net profit margins are 40%. It’s like the most profitable business he’s ever had the opportunity to invest in. You can think of a DuPont analysis as a series of concentric circles.

The innermost circle is sales. This is the company’s product. And it has a profit margin based on how much the company can produce the product for and how much customers are willing to pay the company for the product. The difference is the value the company extracts from its sales. We’ll call sales the inner core of the corporate apple.

Wrapped around that inner core is another circle. This is the company’s assets. The assets have a turnover ratio based on how much sales the company can produce.

Wrapped around the asset core is another circle. This is the company’s finances.

So the return on equity apple looks like this:

Surface / Outer Core / Inner Core

Equity / Assets / Sales

Now, personally I like to look at just tangible assets and equity. I like to separate invested assets – the stuff used in the day-to-day business – from any cash or stocks or bonds the company is holding. And, I like to look at cash flow instead of reported earnings.

If return on equity was a game, the goal would be simple. You have to get capital from deep inside the business out of the business.

When capital gets completely outside a business it becomes cash. If it’s not cash, it’s not yet outside the business. It’s still stuck somewhere along the way.

You do this through leverage.

You want to get a lot of profit from your sales, get a lot of sales from your assets, get a lot of assets from your equity, and get a lot of cash from your equity.

When capital gets completely outside a business it becomes cash. If it’s not cash, it’s not yet outside the business. It’s still stuck somewhere along the way.

The end goal is to get as much cash as possible out of as little equity as possible.

So, here, you want to start with a really small number on the left hand side and finish with a really big number on the right hand side:

Equity > Assets > Sales > Profit > Cash

But that doesn’t happen magically. Financial alchemy works by using equity to support assets, assets to support sales, sales to support profit, and profit to support free cash flow.

So Warren Buffett didn’t just look at the profit margin. He also looked at the volume of business Mid Continent Tab Card Company was doing in relation to the assets they were using.

What was sales/assets? What was the asset turnover ratio?

Because the asset turnover ratio is how you leverage profit. If you have a high ratio of profit divided by sales but a low ratio of sales divided by assets – you end up with only a medium ratio of profit divided by assets.

You’re right that Buffett was worried about margins not being sustainable. But if margins aren’t sustainable — how do you get a decent return on assets even on lower profit margins?

You have a high asset turnover ratio.

His point was that they could manage on a lower profit margin, because the asset turnover ratio would be okay.

The owners of Mid Continent Tab Card Company came to Buffett because they needed his capital to buy an asset – a press. The press was going to make more cards. Buffett needed to know both how many cards the press would make and how much money the company would make on each card.

The issue was never just about how much profit they earned on each card. Buffett wasn’t being asked to invest in one tab card. He was being asked to invest in one press that would make many tab cards that would hopefully make big profits.

That’s key. If assets were expected to grow faster than sales, than a decline in profit margins would be very, very bad. It would lead to much lower returns on assets. That’s your unleveraged return.

Your leveraged return is your return on just the equity in the business. A business’s total assets are supported by (owner provided) equity and (creditor provided) liabilities.

A company leverages its equity by having a lot of assets in relation to its equity. Whenever someone says leverage they mean using a small thing to lift a big thing. A company has a lot of financial leverage when it uses a small amount of capital from owners — equity — to lift a large amount of assets. The only way to do this is to borrow from non-owners.

Borrowing doesn’t just mean issuing bonds or taking out loans. It means borrowing from the IRS by holding stocks forever and thus deferring the capital gains tax forever. The way Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.B ) does. It means borrowing from suppliers by buying supplies on credit and then selling them for cash before you have to pay the supplier in cash. And it means borrowing from policyholders by taking in insurance premiums up front and then paying claims later. The way insurers do.

The point of all of this is that you want to look at how a company generates a lot of cash to send back to owners using just a little bit of equity taken from those owners.

And this is a good way of analyzing the process:

(Net Income/Sales) * (Sales/Assets) * (Assets/Equity) * (Free Cash Flow/Net Income)