Why Quantitative Easing Didn’t Work

Post on: 2 Май, 2015 No Comment

FORECASTS & TRENDS E-LETTER

by Gary D. Halbert

February 11, 2014

IN THIS ISSUE:

1. Why Fed’s Quantitative Easing (QE) Didn’t Work

2. Velocity of Money Plunged During Financial Crisis

3. Should Bernanke & Company Have Done More?

4. QE Was a Huge, Dangerous Experiment That Failed

5. Fed Begins to “Taper” QE Purchases in January

6. Conclusions – What Happens Next?

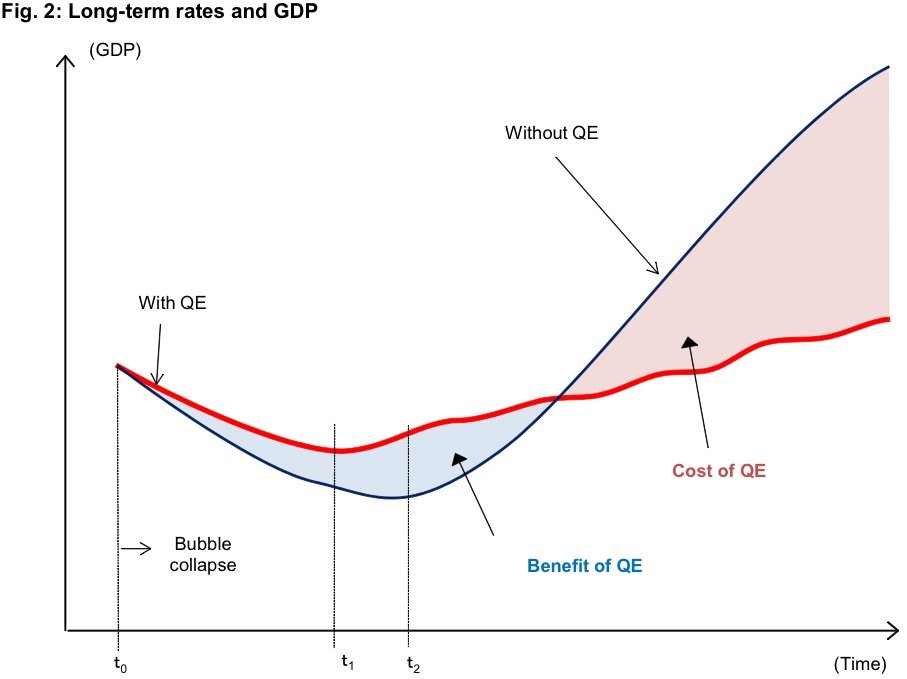

While equity investors yearn for the Fed’s QE policy to continue, it’s actually a good thing that this unprecedented stimulus looks to be coming to a halt by the end of this year or early next year. Why is that a good thing? Because QE hasn’t worked, certainly not as intended.

One of the most frequent questions I get from clients, business associates and even friends is: “Why didn’t quantitative easing work to stimulate the economy and create jobs?” It’s a complicated answer, but today I will do my best to explain why.

Why the Fed’s Quantitative Easing (QE) Didn’t Work

Ben Bernanke, the outgoing chairman of the Federal Reserve, must recognize that he was the victim of the law of diminishing returns. In the initial days of the 2008-09 financial crisis, he mobilized the Fed as the “lender of last resort” and began the process known as “quantitative easing.” This helped quell an intensifying financial panic and, arguably, averted a second Great Depression.

Bernanke’s role during the financial crisis has been much praised, and it’s doubtful that anyone else would have done much better. Yet Bernanke’s ambitions went beyond crisis prevention. He believed the Fed could jump-start the economy by keeping short-term interest rates near zero, along with unprecedented QE purchases of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

Bernanke believed that ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and QE would help reverse the plunge in home prices, boost stock prices, stimulate corporate investment in plants and equipment and thereby generate millions of new jobs for unemployed Americans.

That, of course, did not happen as we all know. Since the recession ended in mid-2009, the economy has grown at a below-trend annual rate of 2.4%. Payroll jobs are still 1.2?million below their 2007 peak, and seven million Americans have left the labor force entirely. Yes, some retired but around half, by most estimates, dropped out because they were discouraged about finding work.

So, what went wrong with Bernanke’s high-minded plans? Why didn’t zero interest rates and massive QE purchases send the economy into overdrive? What Bernanke should have realized is that US consumers, who account for apprx. 70% of economic growth, were scared out of their wits by the financial crisis and were in full deleveraging mode by late 2008 – meaning they were intent on paying down their debts rather than taking on more.

As it was, interest rates fell below 2% on 10-year Treasury notes and near 2½% on 30-year Treasury bonds. Traditional 30-year home mortgages briefly plunged to below 4% in late 2012 and early 2013. The stock markets exploded, more than doubling since their March 2009 lows.

Yet the connections between these financial events and the “real” economy of spending, production and job creation proved frustratingly weak. Higher stock prices should have caused consumers/investors to spend more, but memories of the Great Recession limited this so-called “wealth effect,” again as consumers opted to pay down debt rather than spend more.

Mortgage lending suffered from tougher credit standards, imposed in part by stricter government regulations that banks were all too happy to accept. How was that supposed to help the economy? It wasn’t. Bernanke should have known that too.

Meanwhile, in a 2012 survey of 517 Chief Financial Officers, 68% said that lower interest rates would not cause them to increase their plant and equipment spending. Some CFOs said they financed new investment from internal funds, not borrowing. In short, everyone was scared following the financial crisis.

Velocity of Money Plunged During the Financial Crisis

Simply put, the velocity of money is the number of times a dollar is spent to buy goods and services per unit of time. Put another way, it is the rate at which the same money is exchanged (changes hands) from one transaction to another, and how much a unit of currency is used in a given period of time.

Consider this oversimplified example of the velocity of money: you have a farmer and a mechanic with only $50 between them.

- The farmer spends $50 on a tractor part from the mechanic.

- The mechanic buys $30 of corn from the farmer.

- The mechanic also buys a dog from the farmer for $20.

In these three transactions, a total of $100 changed hands, even though there was only $50 between them. Velocity of money attempts to measure how fast the same unit of money is changing hands.

If the velocity of money is increasing, then more transactions are occurring between individuals, which is good for the economy. If velocity is declining, then fewer transactions are occurring. As you can see in the chart below, the velocity of money has plunged since the late 1990s.

This decline in the velocity of money was directly related to the recession in late 2000 to 2001 and even more in the Great Recession from late 2007 to early 2009. Since the Great Recession was so much more severe, it should not have been a surprise that velocity fell so much more than in 2000 and 2001.

More than four years after the recession ended, you’d think money would be cycling through the economy at a faster rate than a few years ago. But according to the Fed’s data, the velocity of the M2 money supply – which includes cash, checking deposits, savings accounts, money market mutual funds, and CDs – was only about 1.5 times last year. That’s down from 2 times in 2006 and a high of 2.2 times in 1997.

As noted above, consumers were deeply frightened by the Great Recession and were intent on deleveraging. Given this, it should have been no surprise that the velocity of money has fallen significantly and remains at the lowest level in the last 50 years. This is not good for the economy.

Should Bernanke & Company Have Done More?

Surprisingly, some Bernanke critics (largely those on the left) say the Fed should have done more to stimulate the economy. What exactly? Since 2008, the Fed has purchased over $4 trillion in Treasuries and mortgage bonds. Would $5?trillion have saved the world? Come on, really? The simple fact is that QE didn’t work. certainly not as intended.

In addition, Bernanke failed to realize that the Fed lacked the sort of economic control that was taken for granted after Alan Greenspan’s nearly two-decade run as Fed chairman. As Bernanke learned in the later years of QE, the ability of the Fed to steer the economy was largely eviscerated after the financial crisis. As a devoted student of the Great Depression, most analysts assumed that Bernanke knew this.

QE Was a Huge & Dangerous Experiment That Failed

At the end of the day, Bernanke’s weapons were less powerful than assumed or hoped. What subverted their effectiveness was shifting public psychology. The financial crisis and Great Recession changed the way consumers, bankers, business owners and managers thought and behaved.

Before the financial crisis, there was a widespread belief in the economy’s resilience that greatly encouraged spending, borrowing and lending. People unconsciously assumed basic economic stability. After the crisis, there was a residue of fear and caution. Gone was the faith in automatic stability.

As the economy weakened, so did public trust. In 2007, half of Americans expressed confidence in the Fed, but by 2012, only 39% did. Bernanke struggled to make the unpopular case that the Fed’s efforts to prop up the banking and financial systems (aka – “Wall Street”) protected average Americans (aka – “Main Street”) from greater harm.

The consumer mindset of deleveraging and paying down debt weakened the Bernanke Fed, and still does today. This explains why Bernanke’s massive exertions to improve the recovery have so far yielded paltry returns. Monetary policy – the influencing of interest rates, credit conditions and the money supply – is still powerful, but it is no longer some potion that can magically stimulate the business cycle and mechanically restore full employment.

The fate of Bernanke’s easy-money policies is also uncertain. Through the massive QE bond buying and a firm commitment to keep short-term interest rates near zero until the job market strengthens convincingly, he has tried to instill public confidence. Perhaps the lagged effects of these policies will eventually boost more robust economic growth, but so far, it hasn’t.

While it is premature to judge Bernanke’s legacy, his unprecedented QE policies will have ongoing consequences that, for good or ill, will shape his ultimate reputation, which I think will be mediocre at best.

Fed Finally Begins to “Taper” QE Purchases in January

The Fed should have begun to taper QE purchases when Bernanke first floated the idea in May of last year. But the stock market plunged and so he