Why Pension Funds Won t Allocate 90 Percent To Passives Opinion

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By Rachael Revesz | 27 November, 2013

At the IndexUniverse conference in London last week, there were clearly divided opinions about the take-up of passive strategies – both traditional market cap weighted and smart beta – amongst pension funds. However, panellists agreed on one thing: passive funds would not make up 90 percent of pension funds’ allocation.

The reasons were numerous.

Not everyone wants to allocate to markets; smaller pension funds “copying” larger ones is harmful over the longer term; and very clever people in active management will always want to believe they can do better than the market.

Two different panels discussed these topics. Panellists included Nicolas Firzli, director general of the World Pension Council, Nicola Ralston, director of PiRho Investment Consulting and Tim Giles, partner at the global investment practice of Aon Hewitt.

It is true that the 90 percent figure looks a long way off.

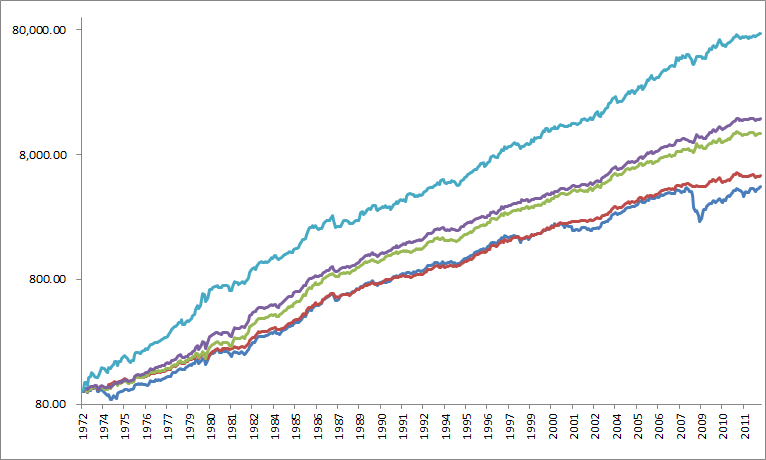

A quick look at the current landscape from Firzli, who estimated that a typical pension fund or insurance fund company allocates 55-70 percent of its assets to traditional, active fund management. This would be about right as the Investment Management Association tells us that 56 percent of UK pension mandates are in index tracking funds. Firzli also estimated that 14-16 percent of total worldwide assets are invested in passive mandates.

Could this rise to 90 percent for pension funds? Not according to our panellists.

“It will be sad and frustrating ten years down the road if 90 percent of what they have is passive, as people want to believe that our investment managers and stock brokers with PhDs and masters degrees can do better than the market by making informed decisions,” said Firzli.

There is a common misconception that passive investing is carried out by robots at computers, or via complicated self-running algorithms. But the rise of passive investing in pension funds surely does not run in parallel with a brain drain in active management.

Nicola Ralston fought back to say that an index is not some kind of abstract reality as in “Plato’s cave”, but it is in fact a human construct and is based on pre-determined rules.

There were other reasons for not hitting 90 percent. Consultant Ralston said it meant assuming all managers want to allocate to markets and they have fixed proportions to asset classes.

“It is assumed that asset allocation is always decided on the basis of X amount to the US equity market and Y amount to the corporate bond market,” she said. “Particularly if you look through the eyes of a fund with £10 million, that [strategy] may be quite an inefficient way to allocate assets.”

Aon Hewitt’s Tim Giles added: “At a market level you can’t see passive being the vast majority as that would lead to greater inefficiencies, and we still believe that active management works.”

Nicolas Firzli pointed out the larger Australian and American pension funds have made significant moves towards passives, with around 20-35 percent of their assets in passive strategies, and the rest in “super active, aggressive” mandates.

The numbers are encouraging overseas, but could smaller or more mainstream pensions in the UK and Europe follow suit?

Ralston, however, voiced a concern that smaller funds should not blindly follow the larger players.

“I worry a lot that smaller funds are made to think that whatever the big funds do is right for them, and often it’s not possible or practical and comes at a high cost – I think it’s one of the most pernicious issues in asset management at the moment,” she said.

The panellists also had different views on whether pension funds’ increasing use of passives would be to the detriment of active management.

Firzli hinted at the “good guys and the bad guys” in fund management. He said active managers tend to use indexing as an excuse for a “herd mentality”.

“In my opinion there’s no real negative effect from the rise of passives,” he said. “This is because, in most instances, passives replace traditional, long-only active management, and if you look at the way traditional stock pickers work, they use indices anyway and don’t tend to move too far away from them.”

Giles, on the other hand, insisted any changes within UK pension funds’ passive equity mandates are from traditional cap weighted indices to fundamental indices due to their more favourable risk reward attributes.

“Where you see alternative indexation being adopted it tends to replace market cap weighted indices, rather than people getting disenchanted with active management,” he said. “Where we look at our track record we can see clear signs of outperformance, compared to passives, but you have to believe in active and you must spend time to make sure you find the right manager.”

Ralston concluded that active and passive are not binary.

“Trying to split them up too much is not helpful,” she said.

It seems that active management will be the mainstay of European pension funds in the near future at least. The rise of passives, whether in market cap or alternative indices, would not radically push active management out of the market.