Why investing in Emerging Market debt

Post on: 9 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Over the summer we have seen a reversal of the often massive flows linked to the ‘quantitative easing’ by the Fed that went into Emerging Markets debt in a quest for yield. These massive inflows helped weaker countries (like India, Indonesia, Turkey and Brazil) to sustain a growing current account deficit and a worsening economic momentum. Since the first talks about the reduction of this quantitative easing — the so called “tapering” — (starting the 22th of May), these weaker countries saw a significant deterioration of their exchange rate and this also led to a drawdown in sovereign local currency bond prices of some 20% in EUR since the high point – thus significantly increasing both spreads and yields. Exchange rates from stronger countries were however significantly less impacted.

This relatively contained sell down is having negative ripple effects throughout the entire region as financial contagion fears have been increasing. Does this mean that we will relive the 1997 Asian crisis again?

If it would, then the effects would be dramatic. Not only has the importance of the Emerging Markets grown significantly, but moreover the developed economies are still very weak. While there are some weak points, we do think that this is not the case as the macro-economic fundamentals have significantly improved since:

- On average the current accounts are still significantly positive, which was absolutely not the case in 1997 when current accounts had started to worsen long before ;

- The percentage of external debt has decreased from around 40% to below 25%. This significantly reduces the reliance on the goodwill of fickle foreign investors. Moreover, in case of a major currency depreciation, the risk of debt spiraling out of control diminishes vastly ;

- The average debt maturities have increased significantly, reducing liquidity risk ;

- Pegged exchange rates have been abandoned. One of the main risks of a pegged system is that excesses can build up to the point where they are no longer sustainable, which then requires a dramatic devaluation. More market-determined exchange rates act as a kind of safety valve ;

- Marked improvement in foreign exchange reserves from 10% in the early nineties to around 30% of GDP today, with a significantly stronger import coverage (= import / foreign exchange reserves) and short term debt coverage ;

- A key source of weakness (poorly regulated and undercapitalized banks) have been addressed through more strict regulation.

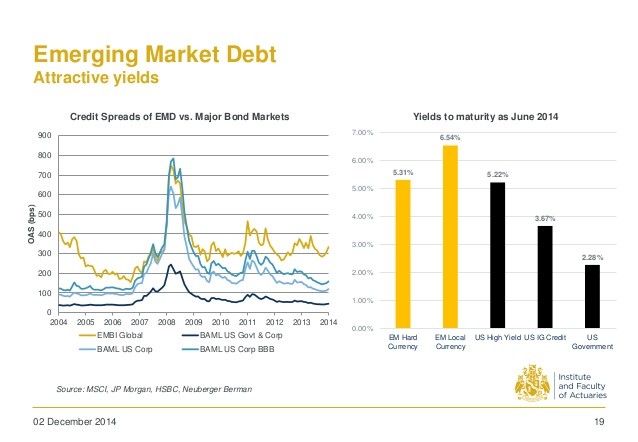

Since the end of August the outflows seem to be stabilizing somewhat. Given that (1) we feel that the economic situation is significantly stronger than what we saw during the Asian crisis and (2) the sell-off has been sufficiently brutal and rapid, an investment in local currency debt from Emerging Markets can be considered. While this sub asset class may not yet be completely mainstream it has become much more “investable” in the past few years. Over the past decade we have seen a marked change in these markets. While at the turn of the century the average rating of this type of bonds was still deep into junk territory, it has evolved to investment grade now. Morevover, the Emerging Market debt markets have become much more liquid compared with the end of the 90s.

Still, given that the situation is far from homogeneous, we prefer to use an actively managed bond portfolio for this region, as we believe that investors should be selective in buying within this asset class. Given the particularities of bond market indices, where those countries with the largest debts get the highest weight in the “market cap” weighted indices, we prefer investing in a portfolio with capped weights. As such, investors limit the exposure to the most indebted countries, thus reducing the overall risk significantly.