Why haven t equity returns been higher

Post on: 4 Август, 2015 No Comment

Christopher Joye

Today I will eviscerate an influential stylised fact in finance that has arguably resulted in the misallocation of hundreds of billions of dollars of Australian savings.

The so-called equity risk premium puzzle, which was identified in 1985 by a Nobel prize- winning economist, purports that listed shares have historically furnished an anomalously large excess return over quasi risk-free assets like AAA-rated government bonds with similar duration.

The puzzle is that equities annual return in excess of government bonds, which Australian academic research alleges is 5 to 6 per cent over the period 1980 to 2010, is too high given the risk differences between theasset classes.

Another implication is that investors are unrealistically cautious: they are demanding excessively high returns to compensate them for equities risks.

Attempts to address the puzzle have consumed hundreds of academic papers. The practical real-world consequences have been more far-reaching.

Australias $962 billion corporate, industry, and public super fund sector frequently uses these excess return assumptions to justify unusually large portfolio weights to Australian and global shares, which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has highlighted as out of line with international peers.

One $40 billion funds default balanced product has just 2 per cent of its money in cash, and 9 per cent in bonds. A remarkable 50 per cent goes into Australian and global shares, with the remaining 40 per cent spread across closely correlated private equity, commercial property equity, and infrastructure equity assets.

The belief that shares offer annual excess returns of 5 to 6 per cent over government bonds also influences the market risk premium assumptions used by several government agencies, including the Australian Energy Regulator when determining acceptable gas and electricity margins.

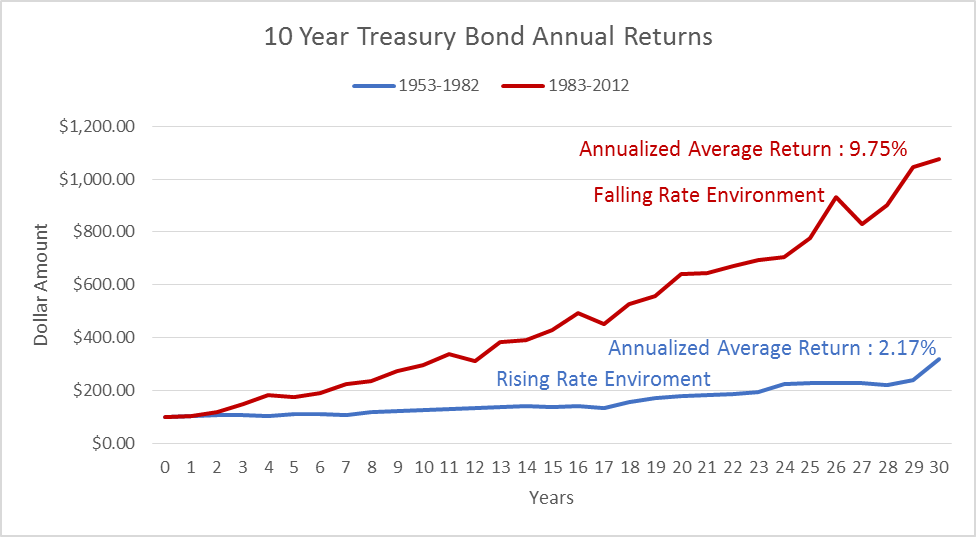

My analysis suggests there is no puzzle. Based on the pre-tax total returns provided by the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index and Australian 10-year government bonds over the past 30 years (with reinvestment), the observed equity premium is very small. These results accord with soon-to-be-published research by Richard Heaney and Stephen Kidd, who use a similar like-for-like holding period approach.

I find that between 1982 and 2012 Australian shares gave a compound annual return of 12.3per cent, with high annual volatility (or risk) of 17.7 per cent.

In contrast, Australian government bonds generated a compound annual total return of 11.7 per cent, with volatility of 8.6per cent. (Analysis before 1980 is plagued by survivorship biases). The numbers are slightly different if one uses arithmetic rather than geometric returns, which is a matter of technical debate.