What rising interest rates will mean for your investments

Post on: 24 Май, 2015 No Comment

Attention, investors: Your world is about to change.

In recent speeches and interviews, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan and other Fed governors are laying the groundwork for an increase in the federal funds rate.

Although this rate applies only to overnight loans between banks, it has a ripple effect on all short- and long-term interest rates and, by extension, on the economy.

Although some prices have already moved in anticipation of higher rates, the story is just beginning.

Related Stories

Today, I’ll briefly discuss how rising rates could affect these investments. In future columns, I’ll delve into what, if anything, investors should do.

It has been almost four years since the last increase in the federal funds rate. In May 2000, the Fed raised it to 6.5 percent from 6 percent.

In January 2001, after the stock-market bubble had burst, the Fed embarked on a series of rate cuts that dropped it to 1 percent, the abnormally low level where it has been since last June.

The Fed wanted to make sure we did not enter a deflationary environment, says Sam Stovall. chief investment strategist at Standard & Poor’s. The Fed has had a lot of practice fighting inflation, but not fighting deflation. They kept the rate low rather than fight something they are not familiar with.

Now that the Fed has declared that deflation is no longer a risk, the only question people have about an interest rate increase is how much and how soon, says Tim Kochis. president of Kochis Fitz.

Investors who gamble on interest rates with federal funds futures are predicting an increase in the rate by September, with a 50 percent chance of an increase in June.

Outgoing Fed governor Robert Parry recently told The Chronicle that if inflation averages 1 to 2 percent, the natural federal funds rate should be around 3.5 percent.

Here’s a look at how rising rates could affect various investments.

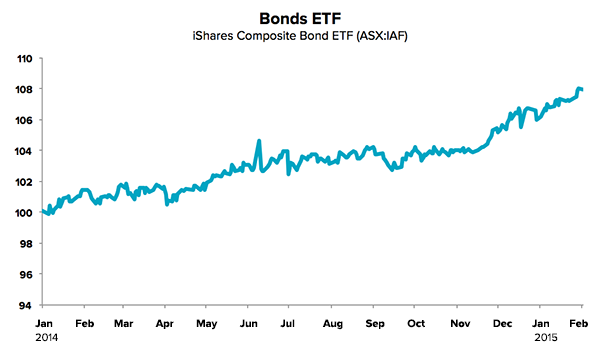

Bonds

Bonds and other fixed-income securities are highly sensitive to interest rate changes.

A bond is a loan. The issuer, usually a company or government entity, borrows money from the investor who buys the bond.

When interest rates rise, the price of existing bonds falls. That’s because investors can get higher rates on newly issued bonds. As a result, the price of old bonds must fall to make them competitive with new ones.

Bond rates are determined by the market, not the government. As a result, bond rates often move in advance of the federal funds rate, as investors try to anticipate the direction of interest rates.

Since mid-March, the yield on the bellwether 10-year Treasury bond has risen to 4.4 percent from 3.7 percent, and its price has fallen 5 percent — more than a year’s worth of interest on the bond.

When interest rates go up, long-term bonds lose more value than short- term bonds, and bonds with low coupon rates will suffer a bit more than similar bonds with higher coupon rates.

Investors who hold bonds until maturity get back the face value of the bond (usually $1,000), no matter what happens to interest rates (assuming the issuer does not default).

Investors who have to sell their bond before maturity will get back more or less than face value, depending on what has happened to interest rates.

Most experts say investors who are buying bonds or bond funds today should stick with shorter maturities, such as one to two years, or five at most.

Money market funds

Those much-maligned money market funds, currently yielding about 0.5 percent on average, are suddenly looking like a good short-term option.

These funds hold Treasury bills and other ultra-short-term debt securities that are replaced every couple of months on average. As the federal funds rate goes up, money fund yields will soon follow. Although money funds are not insured like bank deposits, they are priced at a stable $1 per share, so investors should not lose principal if interest rates rise.

Stocks

In theory, rising interest rates should be good for stocks.

If the Fed raises rates because the economy is growing too rapidly, then corporate earnings should also be growing rapidly and so should stock prices.

In reality, rising rates are often bad for stocks, for several reasons:

— When rates go up, investors who had been buying stocks opt for bonds because their yields are rising.

— The market looks ahead. Stocks rise when investors think the economy and corporate earnings will grow. When the Fed increases rates, it is seeking to restrain the economy.

— Companies that borrow money pay more when interest rates go up. This reduces their earnings.

— Consumers also pay more to borrow money, which discourages them from buying cars. houses and everything that goes with them. This hurts companies dependent on the consumer.

S&P’s Stovall studied the market’s performance (since 1970) after the Fed raised interest rates more than once.

On average, the S&P 500 index was down 5 percent in the six months after the initial rate increase, and down 6 percent in the 12 months after the first rate increase. During the six months preceding the rate increase, the S&P 500 was up 11 percent on average.

The market does not tend to anticipate rate changes very well, Stovall says.

This doesn’t mean the market will necessarily go down this time.

In 1980 and 1999, the market was up six months after the Fed embarked on a series of rate increases.

And on three occasions when the Fed increased rates only once — in 1971, 1984 and 1997 — the S&P 500 was up 4 percent, 4 percent and 19 percent, respectively.

Rising interest rates are usually bad for real estate because it costs more to buy houses and other properties.

Given their steep escalation in recent years, housing prices could be especially vulnerable to rising rates this time.

On the other hand, if inflation becomes a long-term problem and the Fed cannot contain it, housing prices could rise.

Dollar, gold

The U.S. dollar and gold prices are affected by global economic and political forces and do not always behave as expected.

But in general, when U.S. interest rates rise, foreign investors buy more U.S. bonds, and that requires them to buy more dollars, which raises the value of the dollar versus other currencies.

Gold prices are harder to predict, but in general, when the dollar goes up, gold prices go down. That’s the reason given for gold prices sinking below $400 an ounce this week.