What is National Debt Understanding the Debt Crisis

Post on: 11 Сентябрь, 2015 No Comment

What Debt Crisis? A Default Primer for Governments

Abstract: A government that systematically finances spending through unsustainable levels of borrowing eventually finds itself in a crisis. The crisis is often triggered when economic growth slows or interest rates rise, leading to a vicious cycle of larger and larger interest payments. Often, such crises result in default on government debt. The alternative is painful austerity—higher taxes combined with lower spending. The only sure way to avoid both default and austerity is to keep debt low relative to output.

In October 2011, and again in February 2012, Greece defaulted on its external government debts.[1] That might have surprised some, since Greece and its European creditors went to great lengths to avoid using the “d-word”—default. The euphemism employed was “haircut,” as though default were a regular habit of fiscal hygiene.

Creditors, knowing that Greece was unable to pay back its debts, and under pressure from other European institutions, agreed to “write down” about half of what the Greek government owed them. Even with half its debts canceled, Greece is still in trouble; it will likely default repeatedly without ongoing assistance from the EU (read: from Germany).

In order to accurately make economic predictions or policy recommendations in this and similar cases, one needs to understand the scope and nature of the problem of national debt.

What Is National Debt?

National debt, also called sovereign debt, is debt issued in credit markets by a national government. Since countries differ greatly in size and output, economists usually measure national debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

National debt is a bit like personal debt. Governments borrow in order to spend more in the present, and promise to repay creditors in the future. Parents might borrow money in order to invest in a college education, or (less responsibly) use a credit card to take a vacation now that they plan to pay for later. Likewise, a government might borrow to invest in building a seaport, or (less responsibly) sell sovereign bonds—IOUs—to finance an expensive favor for a key voting bloc just before an election.

Like a family, a government can only pay back excessive past borrowing by decreasing spending or consumption relative to income. As many families have learned, reducing spending is harder than it sounds.[2]

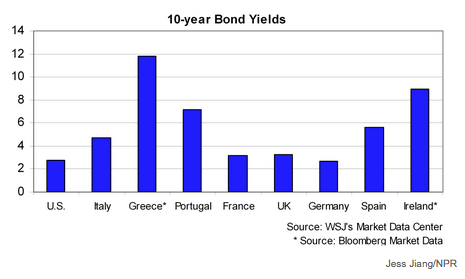

Sovereign debt is more like credit card debt or a college loan than like a mortgage. A mortgage is “secured” by a physical asset. Even if one defaults, the bank can get some value from the loan by seizing the house. But sovereign debt is usually unsecured,[3] which is why these days it is possible to pay a lower interest rate on a new mortgage than the entire country of Italy paid on its recent bond issue.[4]

Glossary

Bond —an IOU issued by a borrower to a lender. It stipulates a specific interest rate, repayment schedule, and possibly other conditions.

Yield —the effective interest rate implied by the bond’s stated interest rate and price of the bond.

Rollover —paying off old bonds by issuing new ones.

Servicing debt —paying interest on outstanding bonds and rolling them over.

The similarities of national debt to personal debt only go so far. The main difference is that countries can grow their way out of debt. When the United States issued billions in debt to pay for its part in World War II, the total amounted to more than 100 percent of GDP. But that ratio—debt divided by GDP—shrank during the post-war boom even without an aggressive effort to pay down the debt. With a growing economy and rising tax base, retiring the wartime debt became a much easier task.

“Outgrowing” debt is very alluring, since it is much less painful than the alternative—decreasing consumption in order to pay down debts. In fact, most sovereign debt now is made with the assumption that the borrowing country’s economy will grow perpetually. As long as debts remain modest or growth rates remain strong, this approach works well. Realistically, however, most countries face decades-long growth slowdowns at some point in their history.

Who Lends Money to Governments?

The creditors who lend their money to governments can be split into two main categories: domestic and foreign. The distinction is important: Typically, foreigners borrow in a globally accepted “hard” currency—most often U.S. dollars or euros. Domestic borrowers typically borrow in the local currency. There are certainly many exceptions to this rule. Notably, with the advent of the euro, high-profile debtors, such as Greece and Italy, have made all their loans in euro terms. Prior to the introduction of the euro, Greece issued domestic debt in drachmas, and foreign debt in German marks, U.S. dollars, and other currencies.[5]

Among both foreign and domestic, there are various types of lenders. These include banks, other financial corporations, hedge funds, pension funds, union funds, foreign and municipal governments, and individual investors, to name a few.

Some of these lenders buy and own government bonds for a long time; others hold them only briefly before selling them to another investor. A successful bond investor will buy bonds cheap and sell them dear, turning a profit on the trade. The prices of bonds in these transactions are public and provide valuable information about the market’s view of a particular government and the prospective costs of future borrowing.

Risk and Return. Because bonds are bought and sold in open markets, higher-risk governments have to offer higher “yield” in order to entice buyers to their bonds.

There are two important sources of risk: (1) a government may refuse to repay all of its debts on time (default) and (2) it may also inflate its own currency, shrinking the value of domestic debt. Both of these tend to occur when governments lack money and courage at the same time.

Occasionally, a government will simply repudiate all its foreign debts. Russia’s revolutionaries in 1918, for instance, refused responsibility for old Tsarist debt.[6]

Much more commonly, governments will “reschedule” the repayment, or partially default on loans. In its mildest form, rescheduling involves delaying interest payments, or unilaterally extending the repayment schedule. Either one is a breach of contract and costs creditors money, but the loss might be relatively small.[7]

More severely, a government may announce that it plans to pay back less than the total value it borrowed. Greece’s case, although the creditors “voluntarily” agreed to the terms, fits into this category, as do the 2001 Argentine default and many others.

Default on domestic debt may be less obvious. When debt is denominated in the domestic currency, a country can escape its debts by inflating the currency unexpectedly. A government that owes both domestic and foreign debts might print much of its own currency, exchange the crisp new bills for hard currency (at a rapidly declining exchange rate), and then use the hard currency to pay off the foreign debts. In one move, the government has shrunk its foreign obligations and its domestic obligations, which are now worth less in real terms, since printing money causes inflation.

Of course, citizens expecting high inflation will not lend their money to the government unless debt pays a correspondingly high rate of return. This can cause a vicious cycle of self-fulfilling expectations. When creditors expect high inflation, they require high interest rates. In order to pay the high interest rates, the government has to inflate. Escaping the vicious cycle is costly and can cause a recession, such as the United States experienced in the early 1980s. Governments have frequently used financial repression to prevent the free movement of funds across borders, essentially trapping domestic savings. That may be good for the regime temporarily, but it is bad for citizens and infringes on their economic freedom, and leads to more severe economic difficulties later.

In addition to inflation, governments have used outright default or rescheduling to escape domestic debt. Economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff document the long history of domestic default, including by several U.S. states in the 1800s.[8]

Governments have to pay higher yields on their bonds if investors consider them to be a high risk for restructuring, default, or (in the case of domestic debt) inflation. The higher the yields, the more expensive it is for the government to borrow. When a government is considered extremely risky, as Greece is now, loans can dry up completely.

Rollover. The cost of paying interest on debt (“servicing”) can increase very quickly. Governments often prefer to sell mainly long-term bonds (10-year or 30-year). But much can happen in a decade, and investors require a higher annual yield before they will buy long-term debt. Thus, governments can save a great deal of money by selling mainly short-term bonds. But when the time comes to pay the short-term bond, the government almost always has to issue a new short-term bond to repay the old one. This is called a “rollover.”

Normally, a rollover is fine. Bond markets are constantly open, and governments are constantly rolling over short-term debt. But when the perceived risk in a country increases drastically, or if bond prices rise for unrelated reasons, annual interest payments can rise rapidly, even without a change in the principal owed.

Households rarely use debt rollover. But one might have had an adjustable-rate mortgage in the 2000s. When interest rates rose, homeowners that once could easily pay their mortgages suddenly found themselves on the brink. Since countries cannot obtain a fixed-rate mortgage, the only way for them to avoid an eventual debt crisis is to keep their total debt level under control.

Crisis!

A debt crisis often plays out like a theatrical tragedy. Everyone can see the sorrowful ending ahead, but nobody can forestall it.

Imagine a small economy on reasonably sure footing, but with a large debt-to-GDP ratio and a history of defaulting on past debts. The country is making annual interest payments equal to 2 percent of GDP and running a balanced budget. Suddenly, a financial crisis elsewhere in the world causes credit markets to tighten: Banks want to hold more cash, and less financing is available for loans in general. The contraction in supply causes the yields on new debt to rise by half. While the country does not need “new” debt, it does need to roll over all of its old debt. Suddenly, the country is paying 3 percent of GDP in interest payments. Without fiscal adjustment, the government is now funding that extra 1 percent in GDP with new deficit spending.

With an extra 1 percent of GDP being sucked out of the country in interest payments and tight credit from banks, a recession is likely. With falling GDP and falling tax receipts, the government might borrow even more.

With debt mounting quickly and a recession underway, the country looks like a worse and worse bet to creditors every month. When it comes time to roll over all that debt yet again, investors are worried about the country’s ability to repay—after all, the cycle of rollover can potentially snowball. Nobody wants to be the last one holding the hot potato, so yields rise steeply.

Facing interest payments of 7 percent of GDP per year and a 5 percent of GDP deficit, the country ultimately decides to cut its losses and default.

Default is not the end of the story; nor are the words “happily ever after.” Countries that default usually fall even further into recession. Foreign investors withhold future credit, sometimes for decades. Trade suffers, the country’s reputation and national pride are tarnished, and the government loses authority in protecting its interests abroad. Moreover, the country must immediately learn to live within its means, even as its means are diminishing. Where it previously used borrowing to ride out recessions, now it must cut services as essential as police protection. The social dislocation of such a crisis episode can lead to political instability and a host of other, unpleasant eventualities.

The Alternative to Default. If a country takes the long view, it may rightly decide that the costs of defaulting are higher than the costs of paying off the debt. But the costs of payment are high, particularly during a crisis. First, the government must balance its budget, often through deep cuts to high-priority spending areas. In the 2012 debt crisis, many European governments are raising taxes. Although a tax hike may increase immediate funds, it lowers future growth and extends the economy’s slump, thereby cutting into revenues.

Whether through cuts to government spending or tax-induced cuts to private spending, a rapid payment of high-interest debt is difficult. A deep recession may result as money is sucked out of the economy to pay foreign creditors. This path is called “austerity.”

A little bit of austerity merely postpones the crisis: The government must run a large enough surplus to pay all of the interest on its debt and a bit of the principle, too. Anything less simply pushes the crisis a few months into the future.

Austerity is most beneficial in anticipation: When a government can convince lenders that it will pay its debts no matter what, it can forefend the vicious cycle of falling confidence and rising interest rates.

Austerity is probably better for most countries in the long run: Future investors will trust the government, wasteful government spending will be cut, and much-needed reforms may be pushed through over the objections of favored interest groups. Default, however, is the easier path, and few governments—or electorates—have the stomach for the painful medicine of austerity.

Doesn’t Borrowing Lead to Growth? Some politicians, and the journalists and economists who enable them, would like voters to believe that they can have their cake and eat it, too. For instance, many news articles refer to the eurozone policies of France’s newly elected Socialist president, François Hollande, as “pro-growth.” But what does “pro-growth” mean? Hollande’s promised borrow-and-spend policies would likely raise GDP in the short run, but would probably also lower private consumption and investment in the short run, and lower growth in the long run, making a future debt crisis in the eurozone more likely. Hollande wants, almost literally, to mortgage his continent’s future for a brief spurt in government spending.[9]

Why do borrow-and-spend policies not work? If the eurozone borrows more from European savers and investors, there will be less savings and investment available for other investments in Europe—such as new factories, research and development, new housing, or student loans. In order for the borrow-and-spend policies to raise long-term growth, the government would have to be more prudent and efficient in its use of the borrowed funds than the private market would have been.[10] Using data from many countries, the International Monetary Fund found that debt has a permanent negative effect on growth.[11]

Conclusion

Large and growing government debt eventually leads to a debt crisis. When economic growth slows, governments can suddenly find themselves pitched from relative debt security to the brink of a crisis.

The nature of debt crises is to be self-fulfilling prophecies of default. Once investors believe that default is possible, they raise the interest rates they charge on loans to the government. The higher interest rates make repayment more costly. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of default, and thus the cycle continues. Once default occurs, a country is typically hammered by a deep recession as investors withdraw credit, trade suffers, and the rapid adjustment of the economy leads to high unemployment.

Governments can choose to implement austerity measures, forcing the country as a whole to consume and invest less than it produces, using the remainder to pay down debt.

Neither option is attractive. So how can a country avoid a debt crisis? The only certain way is to avoid deep debt. A sound economic policy is to keep debt low enough that a calamity or disaster, such as a global recession or war, would not additionally trigger a debt crisis. Exactly how much debt is “too much” varies by country. European countries aim at (and miss) a debt target of no more than 60 percent of GDP. For poorer countries, resource-dependent countries, and countries with a history of many recent defaults, the 60 percent mark is not achievable. Greece, Italy, and Iceland, for instance, have debts that are more than 100 percent of GDP.

—Salim Furth, PhD. is Senior Policy Analyst for Macroeconomics in the Center for Data Analysis at The Heritage Foundation.

consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/128075.pdf (accessed July 11, 2012).

www.stanford.com/

[3] That is, there is no specific asset that can automatically be seized if the borrower fails to repay the loan.

[5] Kerstin Bernoth, Jürgen von Hagen, and Ludger Schuknecht, “Sovereign Risk Premiums in the European Government Bond Market,” Free University of Berlin, Humboldt University of Berlin, University of Bonn, University of Mannheim, University of Munich, Discussion Papers No. 151, 2006.

[7] Ibid. pp. 97–100. In their excellent book on the history of financial crises, Reinhart and Rogoff list 239 instances of sovereign default on foreign debt from 1800 to 2008 across a sample of 66 countries. Every region of the world is well represented, except for the former English colonies of the U.S. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

[9] Since his election, Hollande’s views have evolved rapidly, to the point where it is possible that he might raise taxes and not spending, a classic “austerity” policy.

[11] Manmohan Kumar and Jaejoon Woo, “Public Debt and Growth,” International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 10/174, July 2010.