Understanding California s Property Taxes

Post on: 6 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Executive Summary

The various taxes and charges on a California property tax bill are complex and often not well understood. This report provides an overview of this major source of local government revenue and highlights key policy issues related to property taxes and charges.

A Property Tax Bill Includes a Variety of Different Taxes and Charges. A typical California property tax bill consists of many taxes and charges including the 1 percent rate, voterapproved debt rates, parcel taxes, MelloRoos taxes, and assessments. This report focuses primarily on the 1 percent rate, which is the largest tax on the property tax bill and the only rate that applies uniformly across every locality. The taxes due from the 1 percent rate and voterapproved debt rates are based on a propertys assessed value. The California Constitution sets the process for determining a propertys taxable value. Although there are some exceptions, a propertys assessed value typically is equal to its purchase price adjusted upward each year by 2 percent. Under the Constitution, other taxes and charges may not be based on the propertys value.

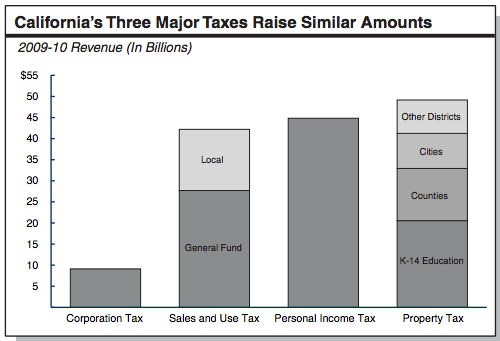

The Property Tax Is One of the Largest Taxes Californians Pay. In some years, Californians pay more in property taxes and charges than they do in state personal income taxes, the largest state General Fund revenue source. Local governments collected about $43 billion in 201011 from the 1 percent rate. The other taxes and charges on the property tax bill generated an additional $12 billion.

The Property Tax Base Is Diverse. Property taxes and charges are imposed on many types of property. For the 1 percent rate, owneroccupied residential properties represent about 39 percent of the states assessed value, followed by investment and vacation residential properties (34 percent) and commercial properties (28 percent). Certain propertiesincluding property owned by governments, hospitals, religious institutions, and charitable organizationsare exempt from the 1 percent property tax rate.

All Revenue From Property Taxes Is Allocated to Local Governments. Property tax revenue remains within the county in which it is collected and is used exclusively by local governments. State laws control the allocation of property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate to more than 4,000 local governments, with K14 districts and counties receiving the largest amounts. The distribution of property tax revenue, however, varies significantly by locality.

The Property Tax Has a Significant Effect on the State Budget. Although the property tax is a local revenue source, it affects the state budget due to the states education finance systemadditional property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate for K14 districts generally decreases the states spending obligation for education. Over the years, the state has changed the laws regarding property tax allocation many times in order to reduce its costs for education programs or address other policy interests.

The States Current Property Tax Revenue Allocation System Has Many Limitations. The states laws regarding the allocation of property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate have evolved over time through legislation and voter initiatives. This complex allocation system is not well understood, transparent, or responsive to modern local needs and preferences. Any changes to the existing system, however, would be very difficult.

Californias Property Tax System Has Strengths and Limitations. Economists evaluate taxes using five common tax policy criteriagrowth, stability, simplicity, neutrality, and equity. The states property tax system exhibits strengths and limitations when measured against these five criteria. Since 1979, revenue from the 1 percent rate has exceeded growth in the states economy. Property tax revenue also tends to be less volatile than other tax revenues in California due to the acquisition value assessment system. (Falling real estate values during the recent recession, however, caused some areas of the state to experience declines in assessed value and more volatility than in the past.) Although Californias property tax system provides governments with a stable and growing revenue source, its laws regarding property assessment can result in different treatment of similar taxpayers. For example, newer property owners often pay a higher effective tax rate than people who have owned their homes or businesses for a long time. In addition, the property tax system may distort business and homeowner decisions regarding relocation or expansion.

Introduction

For many California taxpayers, the property tax bill is one of the largest tax payments they make each year. For thousands of California local governmentsK12 schools, community colleges, cities, counties, and special districtsrevenue from property tax bills represents the foundation of their budgets.

Although property taxes and charges play a major role in California finance, many elements of this financing system are complex and not well understood. The purpose of this report is to serve as an introductory reference to this key funding source. The report begins by explaining the most common taxes and charges on the property tax bill and how these levies are calculated. It then describes how the funds collected from property tax bills$55 billion in 201011are distributed among local governments. Last, because Californias property taxation system has evoked controversy over the years, the report provides a framework for evaluating it. Specifically, we examine California property taxes relative to the criteria commonly used by economists for reviewing tax systems, including revenue growth, stability, simplicity, neutrality, and equity. The report is followed with an appendix providing further detail about the allocation of property tax revenue.

What Is on the Property Tax Bill?

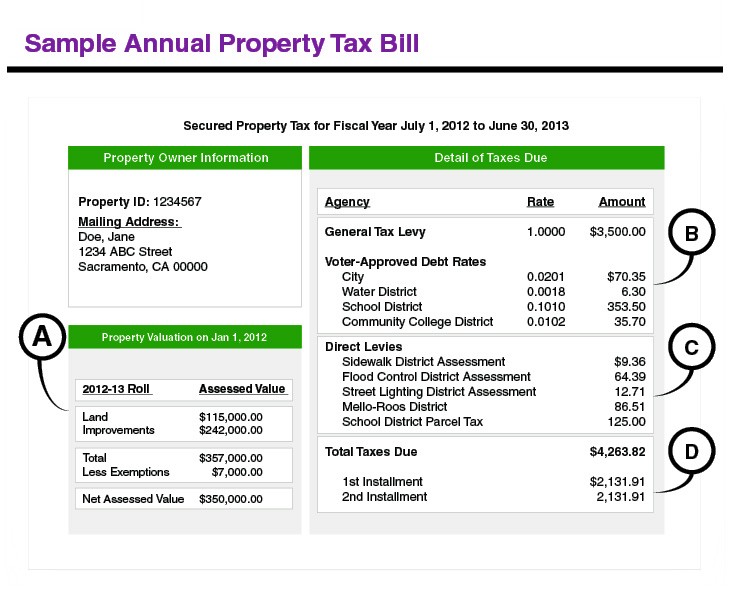

A California property tax bill includes a variety of different taxes and charges. As shown on the sample property tax bill in Figure 1, these levies commonly include:

- The 1 percent rate established by Proposition 13 (1978).

- Additional tax rates to pay for local voterapproved debt.

- Property assessments.

- MelloRoos taxes.

- Parcel taxes.

The Constitution establishes a process for determining a propertys taxable value for purposes of calculating tax levies from the 1 percent rate and voterapproved debt. In our sample property tax bill, Box A identifies the taxable value of the property and Box B shows the propertys tax levies that are calculated based on this value. Levies based on valuesuch as the 1 percent rate and voterapproved debt ratesare known as ad valorem taxes.

Under the Constitution, other taxes and charges on the property tax bill (shown in Box C) may not be based on the propertys taxable value. Instead, they are based on other factors, such as the benefit the property owner receives from improvements.

As shown in Box D, the total amount due on most property tax bills is divided into two equal amounts. The first payment is due by December 10 and the second payment is due by April 10.

How Are Property Taxes and Charges Determined?

Ad valorem property taxesthe 1 percent rate and voterapproved debt ratesaccount for nearly 90 percent of the revenue collected from property tax bills in California. Given their importance, this section begins with an overview of ad valorem taxes and describes how county assessors determine property values. Later in the chapter, we discuss the taxes and charges that are determined based on factors other than property value.

Taxes Based on Property Value

The 1 Percent Rate. The largest component of most property owners annual property tax bill is the 1 percent rateoften called the 1 percent general tax levy or countywide rate. The Constitution limits this rate to 1 percent of assessed value. As shown on our sample property tax bill, the owner of a property assessed at $350,000 owes $3,500 under the 1 percent rate. The 1 percent rate is a general tax, meaning that local governments may use its revenue for any public purpose.

VoterApproved Debt Rates. Most tax bills also include additional ad valorem property tax rates to pay for voterapproved debt. Revenue from these taxes is used primarily to repay general obligation bonds issued for local infrastructure projects, including the construction and rehabilitation of school facilities. (As described in the nearby box, some voterapproved rates are used to pay obligations approved by local voters before 1978.) Bond proceeds may not be used for general local government operating expenses, such as teacher salaries and administrative costs. Most local governments must obtain the approval of twothirds of their local voters in order to issue general obligation bonds repaid with debt rates. General obligation bonds for school and community college facilities, however, may be approved by 55 percent of the school or community college districts voters. Local voters do not approve a fixed tax rate for general obligation bond indebtedness. Instead, the rate adjusts annually so that it raises the amount of money needed to pay the bond costs.

Debt Approved by Voters Prior to 1978

The California Constitution allows local governments to levy voterapproved debt ratesad valorem rates above the 1 percent ratefor two purposes. The first purpose is to pay for indebtedness approved by voters prior to 1978, as allowed under Proposition 13 (1978). Proposition 42 (1986) authorized a second purpose by allowing local governments to levy additional ad valorem rates to pay the annual cost of general obligation bonds approved by voters for local infrastructure projects. Because most debt approved before 1978 has been paid off, most voterapproved debt rates today are used to repay general obligation bonds issued after 1986 as authorized under Proposition 42.

Some local governments, however, continue to levy voterapproved debt rates for indebtedness approved by voters before 1978. While most bonds issued before the passage of Proposition 13 have been paid off, state courts have determined that other obligations approved by voters before 1978 also can be paid with an additional ad valorem rate. Two common pre1978 obligations paid with voterapproved debt rates are local government employee retirement costs and payments to the State Water Project.

VoterApproved Retirement Benefits. Voters in some counties and cities approved ballot measures or city charters prior to 1978 that established retirement benefits for local government employees. The California Supreme Court ruled that such pension obligations represent voterapproved indebtedness that could be paid with an additional ad valorem rate. Local governments may levy the rate to cover pension benefits for any employee, including those hired after 1978, but not to cover any enhancements to pension benefits enacted after 1978. Local governments may adjust the rate annually to cover employee retirement costs, but state law limits the rate to the level charged for such purposes in 198283 or 198384, whichever is higher. A recent review shows that at least 20 cities and 1 county levy voterapproved debt rates to pay some portion of their annual pension costs. The rates differ by locality. For example, the City of Fresnos voterapproved debt rate for employee retirement costs is 0.03 percent of assessed value in 201213, while the City of San Fernandos rate is 0.28 percent.

State Water Project Payments. Local water agencies can levy ad valorem rates above the 1 percent rate to pay their annual obligations for water deliveries from the State Water Project. State courts concluded that such costs were voterapproved debt because voters approved the construction, operation, and maintenance of the State Water Project in 1960. As a result, most water agencies that have contracts with the State Water Project levy a voterapproved debt rate.

Property tax bills often include more than one voterapproved debt rate. In our sample property tax bill, for example, the property owner is subject to four additional rates because local voters have approved bond funds for the city and water, school, and community college districts where the property is located. These rates tend to be a small percentage of assessed value. Statewide, the average property tax bill includes voterapproved debt rates that total about onetenth of 1 percent of assessed value.

Calculating Property Value for Ad Valorem Taxes

One of the first items listed on a property tax bill is the assessed value of the land and improvements. Assessed value is the taxable value of the property, which includes the land and any improvements made to the land, such as buildings, landscaping, or other developments. The assessed value of land and improvements is important because the 1 percent rate and voterapproved debt rates are levied as a percentage of this value, meaning that properties with higher assessed values owe higher property taxes.

Under Californias tax system, the assessed value of most property is based on its purchase price. Below, we describe the process county assessors use to determine the value of local real property (land, buildings, and other permanent structures). This is followed by an explanation of how assessors determine the value of personal property (property not affixed to land or structures, such as computers, boats, airplanes, and business equipment) and state assessed property (certain business properties that cross county boundaries).

Local Real Property Is Assessed at Acquisition Value and Adjusted Upward Each Year. The process that county assessors use to determine the value of real property was established by Proposition 13. Under this system, when real property is purchased, the county assessor assigns it an assessed value that is equal to its purchase price, or acquisition value. Each year thereafter, the propertys assessed value increases by 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower. This process continues until the property is sold, at which point the county assessor again assigns it an assessed value equal to its most recent purchase price. In other words, a propertys assessed value resets to market value (what a willing buyer would pay for it) when it is sold. (As shown in Figure 2, voters have approved various constitutional amendments that exclude certain property transfers from triggering this reassessment.)

Property Transfers That Do Not Trigger Reassessment