There s A Decent Chance Stocks Will Crash Business Insider

Post on: 3 Июль, 2015 No Comment

I think there’s a decent chance that the stock market will crash in the next year or two — maybe dropping 30% or more.

Even without a crash, I think it’s likely that stocks will deliver poor returns from today’s level over the next 10 years. Not negative returns, mind you, but poor returns — average annual returns (including dividends) of only about 3% per year.

Given that stocks are usually expected to return about 10% per year, that’s pretty crappy.

It’s not crappy enough that I’m dumping my stocks. I expect bonds and cash to deliver lousy returns over the next 10 years, too — maybe even worse than stocks. And I’m scared we’ll eventually get some rapid inflation, which stocks should provide some protection from (unlike bonds and cash). But I’m not expecting the double-digit gains we’ve had from stocks over the last few years to continue much longer.

Why not?

Two reasons:

1) Stocks are expensive relative to earnings.

2) Earnings are much higher than normal.

Over the next 10 years, I expect both of those factors — stock prices vs. earnings, and earnings themselves — to regress to means, depressing stock returns in the process.

In other words, I do not think this time is different. I think this time is the pretty much the same. Every other time we have been in a situation like this, stock prices and earnings have regressed to means.

This isn’t investment advice, by the way. It’s just one guy’s opinion. And, as I said, I’m not fleeing the market — because I’m a very long-term investor and because there’s not much else out there that looks attractive to invest in.

Why I think stocks are going to deliver lousy returns over the next 10 years

There’s one thing that most stock-market pundits agree on, including me: Over the long haul, stocks track earnings.

If corporate earnings grow at a compelling rate for a long time, stocks generally follow them up.

If corporate earnings stagnate or tank, meanwhile, stocks generally follow (or even precede) them down.

Of course, this relationship is not tight or direct. Stock prices move much more violently and frequently than earnings, so they oscillate wildly around the long-term earnings trend.

This fluctuation makes short-term stock performance hard to predict. Not only is it hard to predict what earnings are going to do (as you will see in the charts below, earnings do not grow in a smooth, straight line, and analysts almost always miss the turning points). It is also hard to predict what stocks are going to do in response to those earnings.

The smartest approach to individual investing is to stop trying to predict near-term stock and earnings moves and, instead, invest most of your portfolio in low-cost, tax-efficient index funds. That is what I learned to do, after a decade of trying to predict stock moves on Wall Street, and it has served me well. During my decade on Wall Street, I was right a lot of the time and wrong some of the time. That performance actually made me considered a good analyst — I was ranked at or near the top of my category for several years. Alas, when I was wrong, I was really wrong. And those mistakes cost me and my clients a fortune.

Here’s the good news:

As hard as it is to predict stock and earnings performance over the short term, it is relatively easy to predict them over the long term.

Over the long term — 10 years or more — earnings tend to grow at about 6% per year.

Similarly, over the long term — 10 years or more — stocks tend to track that earnings growth. (For the past century or so, stocks have actually returned about

10% per year — the

6% nominal earnings growth plus

4% from dividends.)

Importantly, however, this growth — earnings and stock returns — has not come in a straight line.

Here’s a chart of stock performance relative to earnings performance for the past

150 years. It’s from Professor Robert Shiller, of Yale University, who called both the stock-market bubble of the late 1990s and the housing bubble of the mid-2000s

Note two things:

1) Stocks (black) generally track earnings (green) .

2) Neither earnings nor stocks grow in a smooth, straight line (on the contrary).

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.52.50%20am.png /% Robert Shiller Stocks (black) vs. Earnings (green), 1870-2013

If you listen to Wall Street analysts, you will frequently hear predictions that earnings will grow. And those predictions make sense. Earnings do usually grow.

Alas, sometimes, earnings don’t grow. And when they don’t grow, they don’t generally just sit there. On the contrary, they often tank. And stocks, unfortunately, often tank with them.

Don’t believe it?

Let’s take a closer look at earnings growth, this time over the past half century.

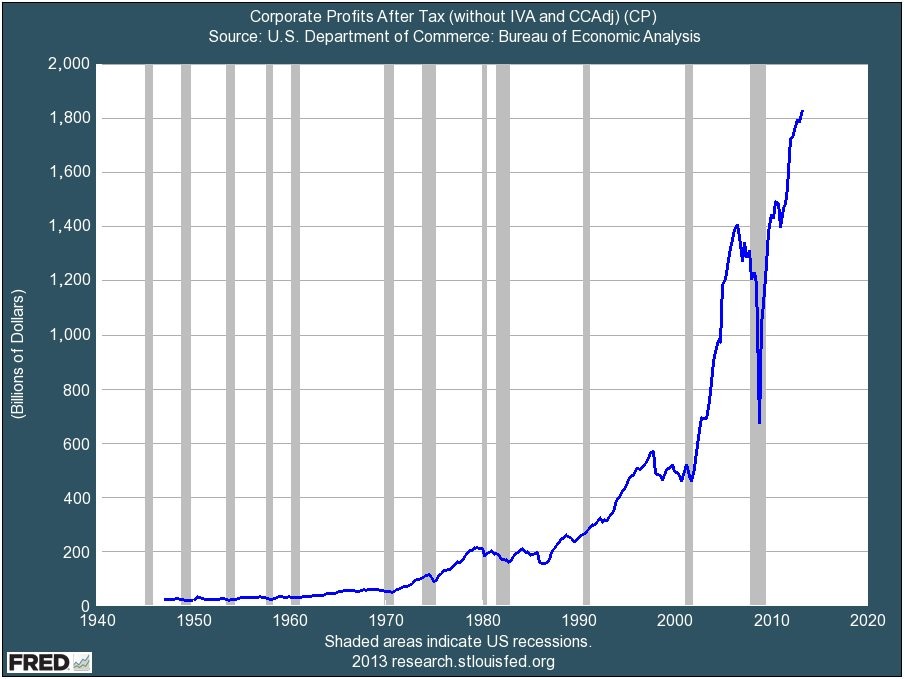

This next chart is from the St. Louis Fed. Note two things:

1) Over the long haul, earnings have grown strongly (

6% per year trend).

2) This growth has been interrupted by long fallow periods and violent crashes.

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.41.21%20am.png /% St. Louis Fed After-tax corporate profits, 1947-2013

The fallow periods for earnings growth included the late 1960s and the early 1980s (both 5-10 years of flat to down earnings). The violent crashes included the late 1990s (

5 years to recover) and the late 2000s (

5 years to recover.)

What causes earnings growth to fluctuate so much?

Well, there are two big drivers of earnings growth:

1) Revenue growth .

2) Profit margins.

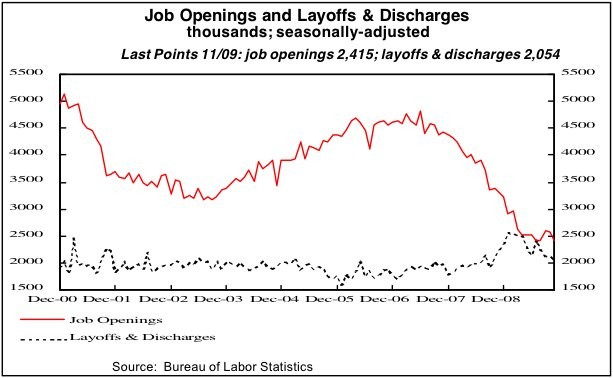

Revenue growth these days is considerably slower than average, because the economy is so weak. What has made earnings grow so much in recent years is not revenue growth, but expanding profit margins.

As the chart below shows, profit margins have expanded so much that they are now at the highest levels in history, by a mile:

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.40.39%20am.png /% St Louis Fed After-tax profit margins.

In addition to noting that profit margins are at the highest level in history, please note something else about this chart: Profit margins are highly volatile, and they have always regressed to (and past) the mean.

If anyone tells you that corporate earnings are just going to keep on growing forever, therefore, ask them the following question:

So, it’s different this time? This time, corporate profit margins are going to stay at the highest levels in history?

(They won’t likely have a good answer for that. They’ll probably bob and weave a bit.)

Even if corporate revenue growth accelerates, this acceleration will not be enough to drive strong additional earnings growth if corporate profit margins regress to the mean. So all those who are predicting that we will have strong earnings growth and excellent stock performance for the next several years had better pray that profit margins don’t regress to the mean.

Now, let’s look at stock prices relative to earnings.

As the long-term chart below shows, again from Professor Shiller, stock prices relative to earnings fluctuate wildly and also tend to regress to means.

Right now, using Professor Shiller’s valuation methodology (which actually attempts to normalize the profit margin problem above), stocks are priced at a very high level relative to earnings.

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.52.32%20am.png /% Professor Robert Shiller S&P 500 price-earnings ratio, 1870-2013 (blue)

Specifically, as you can see in the chart above, stocks are now trading at a price-earnings ratio of about 24X.

That compares to a long-term average of about 16X.

Over the long haul, I expect that price earnings ratio to regress to the mean.

Even if Professor Shiller’s smoothed earnings continue to grow, therefore, I expect stock performance to be poor relative to that earnings growth. And, eventually, sometime in the next decade, I expect stocks to trade at about 16X normalized earnings (earnings on average profit margins).

By the way, I’m not the only guy who thinks stock performance is going to blow.

A fund manager named John Hussman also thinks so.

John Hussman thinks it’s possible that the stock market will go higher from here — in the final speculative blow-off of a speculative bubble — but then he thinks stock performance is going to stink .

Hussman has produced a few additional charts that you should definitely take a look at.

First, here’s a chart in which Hussman compares profit margins (blue) to future earnings growth (red). The profit margin line (blue) uses the left-hand scale and shows profit margins at any given time. The earnings growth line (red) shows annualized future 4-year earnings growth from that point in time.

What the chart shows clearly is that high profit margins today produce lousy earnings growth over the next several years, and vice versa. And the chart also shows, again, that today’s profit margins are the highest they have ever been.

For what it’s worth, John Hussman expects earnings to shrink by 5%-15% per year for the next 3-4 years. Imagine what stocks will do if earnings do that!

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.25.02%20am.png /% Hussman Funds

And now for stocks.

In case you’re skeptical about the value of earnings analysis, John Hussman includes two charts comparing stock performance with other valuation measures. The first compares price-to-revenue (blue line) with subsequent 10-year stock performance. It tells the same story as the earnings analysis. In fact, this analysis suggests that stock price performance will be negative for the next 10 years. (Fortunately, we should collect some dividends, which should boost returns to about 3% per year.

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.23.11%20am.png /% Hussman Funds

Hussman’s second valuation analysis compares the market value of non-financial stocks relative to GDP with future 10-year stock performance. It tells the same story: lousy future stock performance.

20shot%202013-09-26%20at%205.23.38%20am.png /% Hussman Funds

So, is the stock market going to crash?

I don’t know.

But it certainly wouldn’t surprise me. Today’s record-high profit margins will probably correct at some point, and when they do, I expect stocks will follow.

What would really surprise me, meanwhile, is if stocks kept rocketing upwards at 10+% per year the way they have over the past four years.

Unless we get rip-roaring inflation, which is certainly possible (and, in fact, is another important reason to own some stocks), I expect stocks to do poorly over the next 10 years. And after adjusting for inflation, regardless of what it turns out to be, I expect stocks to be trading at about this level in another 10 years.