The Tycoons How Andrew Carnegie John Jay Gould and Invented the

Post on: 7 Август, 2015 No Comment

Synopses & Reviews

Publisher Comments:

An original and compelling portrait of how four determined men ascended to unrivaled wealth, productivity, and world dominance after the Civil War.

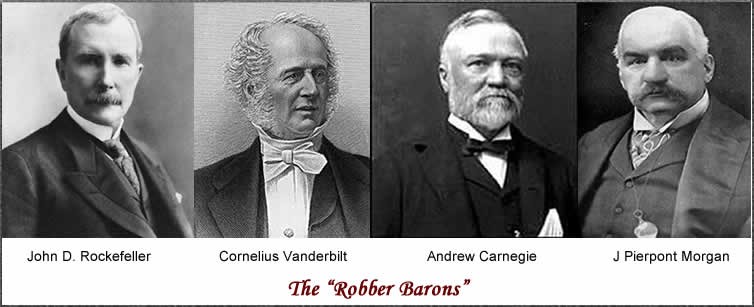

What we think of as the modern American economy was the creation of four men: Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan. They were the giants of the Gilded Age, and lived at a moment of riotous growth and real violence that established America as the richest, most inventive, and most productive country on the planet. They are, quite literally, the founding fathers of our economy and, thus, of modern America.

Acclaimed author Charles R. Morris vividly brings the men and their times to life. The ruthlessly competitive Carnegie, the imperial Rockefeller, and the provocateur Gould were obsessed with progress, experiment, and speed. They were balanced by Morgan, the gentleman businessman, who fought, instead, for a global trust in American business. Through their antagonism and their verve, they built an industrial behemothand a country of middle-class consumers. The Tycoons tells the incredible story of how these four determined men wrenched the economy into the modern age, inventing a nation of full economic participation that could not have been imagined only a few decades earlier.

About the Author

What Our Readers Are Saying

Average customer rating based on 1 comment:

OneMansView. October 26, 2010 (view all comments by OneMansView )

Celebration of tycoons ignores deeper realities (3.25*s)

This book is a glimpse into the extraordinary transformation and growth of the American economy that started during the Civil War but accelerated tremendously over the next forty years. The Civil War was a time of westward expansion under the Homestead Act, neo-Whig infrastructure development, especially railroads, and the rise of corporations to supply wartime needs. Those trends continuing after the War, the author’s four tycoons are representative of men who saw the opportunities and advantages in dominating such core industries as railroads, iron and steel production, and oil extraction and refining, all undertaken in a favorable environment that erected barriers against foreign competition but with few domestic regulations. It should be noted that the book is far more an examination of the logic for developing large enterprises than it is biographical.

A legitimate question that the author addresses is what was the basis of this astonishing economic surge? The short answer is immense natural resources, necessity, and ingenuity, in addition to an advantageous legal setting. The ever expanding population virtually required that huge enterprises come into existence that were capable of making the capital investments to meet their needs. Fortunately, America had the iron ore, oil deposits, rich farmlands, vast plains and waterways, etc which large businesses could exploit to meet the demands for transportation and durable goods.

Yankee ingenuity does not get short shrift in the author’s account. He points especially to the Connecticut River valley as a hub for developments in manufacturing. Machinery was designed to produce to tight tolerances the interchangeable parts necessary for the mass production of guns, farming machinery, consumer goods, etc. However, this mechanization did not come without fundamental social impacts. Employers became far less dependent on skilled artisans for production; quickly trained, lowly paid, and easily replaced machine-tenders became mere cogs in manufacturing. The author little appreciates that this power imbalance in the workplace was a constant source of conflict and was not effectively addressed until the CIO unionization drives of the 1930s. On the other hand, as the author points out, never before had so many affordable products become available to the middle-class. Apparently, the status of being a middle-class consumer was a substitute for the loss of status as an independent, skilled producer.

The author merely sketches the early lives and the personal characteristics of these four individuals. All were smarter than the next guy, were driven, and could be ruthless, as well as deceitful. The author describes the basic business dealings of each individual that propelled them to rise above their competitors. In addition, all seemed to have mastered navigating the treacherous, that is, unregulated, financial waters of the times involving stocks, bonds, and the like. Unfortunately, most of that financial wheeling and dealing is the most confusing aspect of the book.

Despite theoretical claims that competition is key to capitalism, the last thing that companies with large capital investments want is competition. To control pricing a company must dominate its sector by getting bigger, merging with others, or joining pools or cartels. All of these men, especially Carnegie and Rockefeller, using those mechanisms, achieved the kind of dominance that permitted them to generally control the marketplace. Nonetheless, the broader American economy was prone to panics and downturns throughout the 19th century. It was J.P. Morgan, banker extraordinaire, who was powerful enough to bring stability to financial markets through judicious injection of funds, among other measures. The author indicates that Morgan acting as a conservative force actually performed the role that the Federal Reserve was created for in 1913.

The author basically ignores or downplays the reactions of American workers and farmers to the control that these large enterprises had in the economy and over politicians and to the depressions and deflation of the late 19th century. He mentions the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Haymarket Square bombing of 1886, and the Homestead strike of 1892 against the Carnegie works, but does so to generally show the irrational and violent reactions of workers. The largest worker organization of the times, the Knights of Labor, gets no mention, and the entire Populist movement gets a mere wave of the hand. Their concerns that enormous economic entities are not compatible with citizen democracy are not without merit. The author does acknowledge that the free laborer that Lincoln extolled, who would someday become an owner, had become more illusion than reality.

To the author’s credit, he does note that the managerial strategies that began with the tycoons and lasting beyond WWII, that is, vertical integration, regarding workers as merely replaceable pieces, etc, have proven to be a prescription for failure. According to him, the just-in-time reliance on a network of suppliers and relying on smart production workers has made Toyota a model manufacturer.

It is interesting to see the basic paths these individuals took to reach economic heights, though a full understanding will require referring to other sources. The author does provide some correctives to negative perspectives about these individuals, especially Rockefeller. But the book questions too little. Did America sign up for dominant corporations and individuals in 1787? Can a democracy really exist in the face of narrowly held economic power? What is super about an economy that tolerates fairly high levels of poverty and unemployment? Celebrating tycoons does not really address those fundamental questions.

Was this comment helpful? | Yes | No

(8 of 11 readers found this comment helpful)