The Louvre Accord The Fight Against Deflation

Post on: 16 Август, 2015 No Comment

The Louvre Accord of February 1987 was agreed to by the then G-6 nations of West Germany, France, Great Britain, Japan, Canada and the United States to stop United States dollar depreciation. To understand the purpose of these accords, the prior 1985 Plaza Accord must be understood in terms of allowing the dollar to slide 20% against the Japanese yen, 15% against the French franc and 15% against the German Deutsch mark. All the G-6 nations feared inflation and the ability to sustain five years of constant economic growth since 1982.

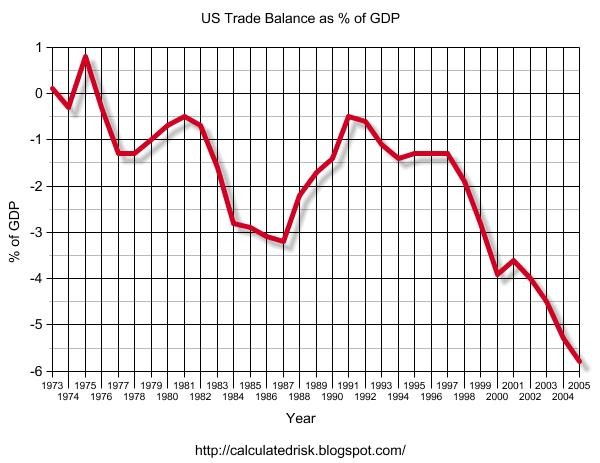

With two years of dollar depreciation agreed to in 1985 with the Plaza Accord, the United States was sustaining huge twin deficits in its domestic and current account budgets. In 1986, the trade deficit rose to approximately $166 billion with exports at about $370 billion and imports at about $520 billion. The trade deficit alone approached approximately 3.5% of the GDP. while the Japanese had a surplus of 4.5% and the Germans 4% of the GDP. Not only were foreigners tired of financing U.S. trade by purchasing United States Treasury bonds and importing inflation into their own nations, but Democrats gained control of Congress in 1986 and called for protectionist measures. (To learn about the Plaza Accord, check out The Plaza Accord: The World Intervenes In Currency Markets .)

What Made The Louvre Accord Different?

What separated the Plaza Accord from the Louvre Accord was that the Plaza Accord was a trade agreement, one that would be reached by the realignment of currencies to satisfy acceptable levels of trade for all nations. The United States went from surplus to deficit in two years. The U.S. complied, however, as the dollar index on the NYBOT fell from 130 to 123 in two months in 1985 and from 124 to 108 in 1986. These dollar levels proved to be unacceptable as twin deficits mounted in the United States and surpluses increased in Europe and Japan. The Louvre Agreement was convened to stop the slide of the dollar and achieve currency price stability among all industrialized nations.

What made the Louvre Accord such a historic document was its focus not only on realignments but on the coordination of macroeconomic fiscal and monetary policy for all nations. France agreed to reduce its budget deficits by 1% of GDP and cut taxes by the same amount for corporations and individuals. Japan would reduce its trade surplus and cut interest rates. Great Britain would agree to reduce public expenditures and reduce taxes. Germany, the real object of this agreement because of its leading economic position in Europe, would agree to reduce public spending, cut taxes for individuals and corporations, and keep interest rates low. The United States would agree to reduce its fiscal 1988 deficit to 2.3% of GDP from an estimated 3.9% in 1987, reduce government spending by 1% in 1988 and keep interest rates low.

Combining fiscal and monetary policies, the accord was believed to be capable of stabilizing any imbalances in the system and allowing economic prosperity to move forward, provided that coordination remained the focus. (For more, see Get To Know The Major Central Banks .)

Improving on History

A final aspect of the Louvre Accords was the focus on least developing nations, which followed the same policy as the Plaza Accords. Due to a falling dollar over the prior two years, least developing nations were experiencing high commodity prices, high inflation, an inability to participate in the world trading system and rising debt owed to banks in the industrialized nations subject to these agreements. So again, a new agreement was needed to stabilize the system for least developing nations. (To learn more, check out The Basics Of Tariffs And Trade Barriers .)

The real breakdown of the Louvre Accord would occur in October 1987, when the Germans increased short-term interest rates from 3.60 to 3.85 due to inflation fears. This forced the United States to raise its discount rate as the federal funds rate increased to 7%. The increased rates forced the 30-year Treasury bond to peak to 10.25% and sent the U.S. stock market tumbling some 500 points. The dollar eventually traded down to 86 and far exceeded the reference range bands. The Japanese and Great Britain would also see rate increases. By January 1989, the Germans had introduced a withholding tax on interest income so any chance of a rescue of the Louvre Accord had disappeared.

The Bottom Line

What the breakdown of the Louvre Accords gave the world was an absence of further agreements to fix exchange rates. Instead, floating exchange rates would be governed by the market, rising and falling based on inflation and interest rates. (To learn more, see Forces Behind Exchange Rates .)