The Greenback Bull Market Is Coming

Post on: 1 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

The Greenback Bull Market Is Coming

By: Suzanne McGee

Published: December 17, 2013

It will make a fashionably late appearance, but the dollar rally is expected to arrive in 2014. We’ve been waiting for it since the Federal Reserve first broached the idea of tapering in May, and interest rates began moving higher as a result. Rates on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages are about 25 percent higher now than they were at the start of this year. Ten-year Treasury yields are up a full percentage point over the same period.

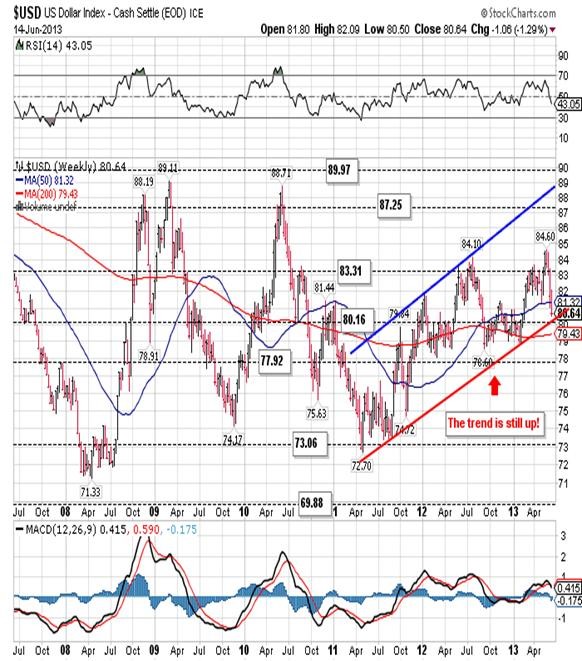

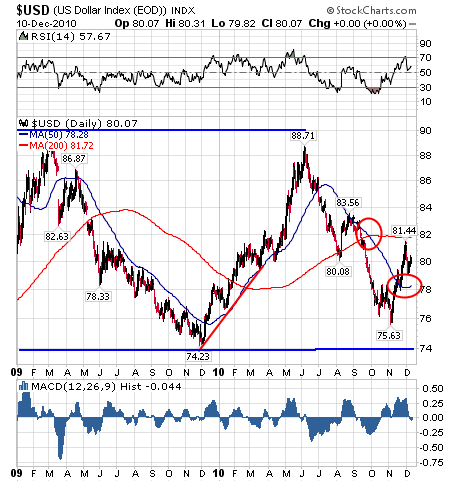

Historically, periods of higher interest rates have been linked very closely to strength in the greenback. But these cycles are multi-year periods, and what happens during any given six- or 12-month timespan within that time frame might not be the same as what happens over the cycle as a whole. So, even though the dollar’s value has moved up, down and sideways at various points this year, Credit Suisse’s foreign exchange analysts say in a recent report called “2014, The Year of the Dollar” that a larger trend is visible on the horizon. A multi-year bull market in the U.S. currency will begin in the new year, according to their forecasts.

In an early October report, the analysts noted that the dollar rally had stalled against the G10 currencies. Despite weakening a bit this month, the dollar has been trending higher since mid-October. The Bank of England’s effective exchange rate data shows that at 86.54 as of Dec. 13, the dollar is approximately 6 percent stronger than it was at the beginning of the year. Credit Suisse expects the trade-weighted dollar index to rise to 90.70 over the next three months and to 95.99 over the coming year.

The analysts say a likely divergence in monetary policymaking among the world’s largest central banks in the New Year should give the rally traction. Consider the following three examples:

–While pundits expect the Fed to start reducing quantitative easing measures either this month or next, the Bank of Japan is widely expected to step up its own asset-buying program early next year.

–With inflation at worryingly low levels, the European Central Bank is not only unlikely to raise rates, but could actually ease further.

–The mining investment boom that had thus far helped Australia to avoid most of the negative effects of the Great Recession has just about run its course. Credit Suisse’s analysts expect mining investment to peak at about 8 percent of GDP this year. The Australian economy is due for a major rebalancing, and if the value of the Aussie doesn’t fall on its own, the Reserve Bank of Australia will come under more pressure to push it down by cutting interest rates again. The central bank already made 25-basis-point cuts in both May and August of this year, leaving the current cash rate at 2.5 percent.

As a result of the above, the Credit Suisse analysts expect the yen and the Australian dollar to fall “substantially” against the greenback, and for the euro to follow suit later on. They expect the dollar-yen exchange rate, for example, to rise to 120 yen for every dollar from its current level of about 103, according to the most recent forecasts in a Dec. 11 report called “A Differentiated December.” And while an Australian dollar now gets you about $0.89, a year from now, it will only get you $0.80 this time next year, the analysts forecast. Similarly, a single euro will currently buy you about $1.38, but they expect that to fall to $1.24 by next December.

And the analysts don’t expect the moves to be short-lived. Rather, they consider early 2014 to be the long-awaited start of a period of dollar outperformance of a kind that historically has lasted anywhere from six to nine years. It took six months for the divergence to get going, so the dollar’s response to interest rate changes is neither automatic nor immediate. Indeed, in seven out of eight recent periods in which interest rates rose – the first in March 1972 and the most recent in June 2004 – the dollar actually lost value in the first year of each multi-year cycle before eventually following the more logical trajectory of strengthening.

Investors were not simply being irrational by shunning dollars just as they are expected to begin appreciating. Consider what it means to “own,” or to be long, the dollar. Most investors seeking a way to profit from changes in exchange rates turn to government bonds, and in the case of the dollar, that means Treasuries. Given the size of the U.S. government’s current account deficit, which is financed with regular auctions of Treasury bills and notes, odds are that these investors already have a significant chunk of Treasury securities in their portfolios. And as rates were rising, they were watching the value of those assets erode. With little clarity on just how far rates could go, the risk of buying too soon was akin to doubling down on an unfavorable investment—and the possibility that the new purchases would soon be declining in value as well. What we witnessed for much of 2013 is the outcome of that thought process in action. As the yield on the 10-year Treasury has risen, foreign owners of these bonds have responded by selling, rather than by buying more.

Markets have for some time been expecting the Federal Reserve to start reducing monthly asset purchases either in December or January, and Credit Suisse forecasts that U.S. Treasury yields are likely to stabilize soon at a new, higher level (around 3 percent on 10-year notes, up from 2.86 percent now). Considering both of those things, history and logic suggest that investors would focus less on their recent capital losses (and the fear of adding to them) and more on the opportunity presented by higher yields. That mindset shift seems now to be under way, if belatedly so. It’s a great reminder that even if two market trends tend to frequent the same parties, they may not always arrive together.