The Federal Reserve’s Approach to Monetary Policy

Post on: 5 Август, 2015 No Comment

Control versus Influence

The U.S. economy is a huge, complex network of markets and institutions. Millions of individuals make decisions every day that affect the course of the economy to some small degree. To think that anyone or any agency controls the economy is an act of intellectual arrogance. The Federal Reserve System, which oversees the nation’s monetary system and has the power to create money, is no exception to this rule. The Fed has the ability to influence the behavior of the economy in important ways. Extremely poor monetary policy could do extensive damage to the economy. But in no real sense does the Fed control the economy.

Aggregate output (Y ) and the aggregate price level depend upon the strength of aggregate demand for goods and services, the current costs of production, and the productive factors — labor, physical capital, human capital, and technology — available to producers. As we shall see, through its monetary policy actions, the Fed can influence aggregate demand in relatively predictable ways. However, the Fed has no direct control over the supply side of the economy. Current costs of production reflect the historical development of the economy. The factors of production are almost wholly outside the Fed’s influence. No government agency, no matter how powerful it might seem, can effectively control the economy merely by influencing the level of aggregate demand. This is not to say that monetary policy is unimportant; far from it. Good policy aids in the efficient operation of the economy, while bad policy can cause recessions and even (in the extreme) lead to a slower rate of economic growth. However, influencing or adjusting the path of the economy hardly amounts to controlling it.

How the Federal Reserve Influences the Economy

The Federal Reserve affects the economy through it ability to control the quantity of Federal Reserve money in existence. Federal Reserve money serves two purposes: We carry around Federal Reserve notes in our wallets (currency held by the non-bank public), and banks hold Fed money as bank reserves in the form of Federal Reserve notes in their vaults or deposits in the twelve district Federal Reserve Banks. By influencing the quantity of bank reserves, the Fed can influence the amount of loans extended by the banking system, the interest rate at which those loans are extended, and the quantity of deposit money created in the process of lending.

The Fed’s strategy of monetary policy links the Fed’s monetary policy tools to aggregate demand. We will concentrate on open market operations, since OMO are the most important and frequently used tool of policy. The Fed’s policy strategy can be shown schematically as follows:

In words, an open market operation affects the federal funds rate, which in turn affects the market rate of interest and (if inflationary expectations are constant) the expected real rate of interest, which in turn affects business spending on investment goods, thereby affecting aggregate demand. Thus, the manner in which the Fed influences aggregate demand is quite indirect.

The Federal Funds Market

Banks routinely borrow cash reserves from other banks or lend reserves to other banks. An active market exists for inter-bank loans of reserves. This market is called the federal funds market. because the reserves that are traded are immediately available to satisfy Federal Reserve requirements. The interest rate charged on such loans is called the federal funds rate. The federal funds rate is determined by the demand for and supply of reserves in the inter-bank loan market. The demand for reserves is negatively related to the federal funds rate, because at a lower funds rate, bankers see more profitable lending opportunities and are more anxious to borrow reserves and extend more loans. At higher federal funds rates, fewer profitable lending opportunities exist, and banks desire a smaller quantity of borrowed reserves.

The supply of bank reserves is controlled by the Federal Reserve. The Fed creates reserves by purchasing U.S. Treasury securities on the open market. When the Fed buys bonds, it injects newly created reserves into the banking system. (These reserves enter the system via the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s computer.) When the Fed sells bonds, it withdraws reserves from the banking system. We portray the supply of bank reserves as perfectly inelastic, because the Fed can choose to inject whatever quantity of reserves it wishes into the banking system.

The federal funds rate is determined by the interplay of demand for and supply of reserves on the inter-bank loan market.

By increasing or decreasing the quantity of reserves in the banking system, the Fed can lower or raise the federal funds rate. Suppose the Fed determines that it should raise its federal funds rate target to 6%, from its current level of 5.5%. Then the Fed sells bonds on the open market, reducing the supply of reserves in the banking system and pushing the federal funds rate upward.

From the Federal Funds Rate to the Market Rate of Interest

The act of raising the federal funds rate affects banks in two ways. First, the supply of reserves available to support deposits — and loans — is smaller. Second, the marginal cost to banks of obtaining reserves with which to make loans is higher. Banks respond to the higher marginal cost of reserves in much the same way that other monopolistically competitive firms react — by raising the price of their product. In the case of banks, the main product is loans, and the price of loans is the interest rate.

The market interest rate is determined in the loanable funds market. This market brings together borrowers and lenders. In keeping with the approach of your text, we will treat the demand for loanable funds as being determined by the desire of businesses to finance investment projects. The demand for loanable funds slopes negatively, indicating that firms are willing to borrow more when the interest rate is low than when it is high. This reflects the fact that more prospective investment projects are profitable when the cost of borrowing is low than when the cost of borrowing is high.

The supply of loanable funds combines the saving of households, businesses, and governmental units with new credit issued by banks. When banks increase their lending, they create credit (and deposit money), adding to the funds available for investors to borrow. The market interest rate is determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds.

A sale of bonds by the Federal Reserve, which decreases the supply of reserves and increases the federal funds rate, causes banks to raise their interest rate and offer fewer loans. The supply of loanable funds shifts to the left, and the market interest rate rises.

From the Market Rate of Interest to Aggregate Demand

When the Fed pushes the market interest rate upward, it typically also increases the expected real interest rate. Recall that re = i — pe. If the expected inflation rate remains constant when the market interest rate rises, then the expected real interest rate also rises. The increase in the expected real interest rate reduces the demand for investment goods by businesses, since the perceived cost of investing has increased. But a reduction in investment spending reduces aggregate demand. The AD curve shifts to the left, reducing the incipient pressure on prices that exists at Y0 in the following aggregate-output diagram.

When Does the Fed Want to Raise the Interest Rate?

Why did I choose to raise the interest rate in the preceding example? And what did I mean by incipient pressure on prices? Note that the level of output Y0 exceeds the natural output level. By definition, the natural output level is the maximum output level consistent with price stability. When Y rises above Yn. demand pressure in factor markets begins to raise the cost of production for firms throughout the economy. Firms respond to higher costs by increasing prices. But this process takes time. Aggregate demand must work its way down through the retail, wholesale, and manufacturing sectors before it affects the factor markets. Even then, factor prices don’t begin to rise immediately. At least that’s the case in the most important factor market — the labor market. Wages are quite sticky; they don’t rise immediately after the demand for labor increases. Thus, if the Fed can act quickly enough, it may be able to head off wage and price increases by reducing aggregate demand (and the demand for factor inputs). If the Fed succeeds in shifting AD back to AD1, the pressure on wages and other factor prices may be minimized, and the consequent price increases avoided.

Always on the Lookout

Since inflation is so costly to stop once it’s underway, the Fed takes great pains to avoid letting inflation become established in the economy. Thus, the Fed constantly watches a host of economic variables in an attempt to determine where the economy is relative to the natural output level. The variables the Fed pays attention to include the following:

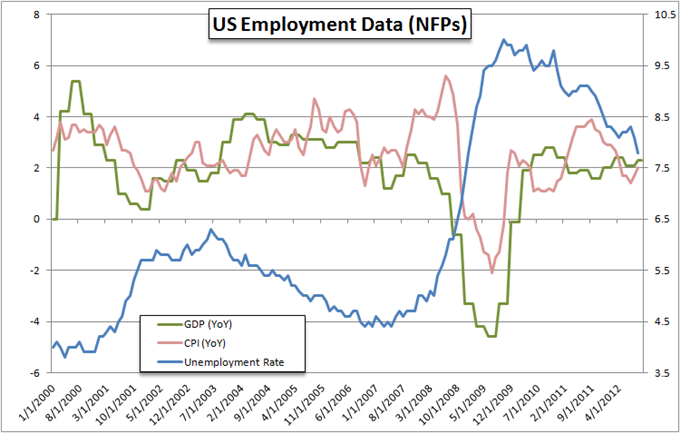

- How rapidly Y is growing compared to the estimated sustainable growth rate (the growth rate of Yn )

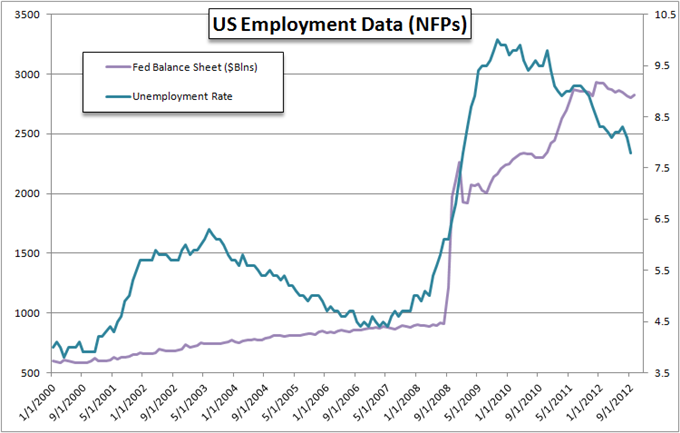

- The unemployment rate and the behavior of employment costs

- Commodity prices

- The extent of manufacturing inventories and backorders (orders that can’t be filled immediately)

- Global economic conditions

Each of these categories provides Federal Reserve policymakers with important information on the probable future behavior of prices. The Fed estimates the growth of Yn by estimating how rapidly the labor force is growing, how rapidly the capital stock is growing, and how rapidly technology is improving. In other words, they utilize the output equation Y = A .F (K. H. L ) along with estimates of how rapidly A. K. H. and L are growing to estimate the sustainable growth rate of the economy. If actual output grows significantly faster than their estimate of sustainable growth, the Fed is likely to act to slow down the economy. On the other hand, if the economy seems to have excess capacity, the Fed will encourage aggregate demand to grow in order to pull actual Y up to equality with sustainable Y .

The unemployment rate is an indicator of tightness in the labor market. When the unemployment rate is too low, workers have enough bargaining power to force wages to rise faster than labor productivity. When this occurs, unit labor costs increase, and firms pass these higher labor costs along to consumers in the form of higher prices. The safe level of unemployment, which we call the natural rate of unemployment, is the lowest unemployment rate consistent with stability of unit labor costs. I.e. it is the lowest unemployment rate at which wages rise at the same rate as labor productivity. This is the unemployment rate that coincides with the natural output level (Yn ) in the output market. When u falls below un (and Y rises above Yn ), wages begin to rise faster than labor productivity, generating inflationary pressure in the economy. The Fed is likely to raise interest rates when they perceive this to be happening.

Commodity price increases typically precede price increases at the retail level. Thus, the Fed often tightens monetary policy when they observe commodity prices rising.

Inventories and backorders are a measure of the ability of the manufacturing sector to meet product demand. When inventories are high, firms are not likely to raise prices. However, when inventories are low and backorders are high, firms have more market power, and price increases are more likely.

Finally, global economic conditions can affect the economy in important ways. For example, should Europe move into a strong expansion, Fed policymakers would expect the demand for U.S. exports to increase. An increase in net exports would cause aggregate demand to increase, putting more pressure on prices. The Fed might act to reduce domestic spending (through higher interest rates) to offset the increase in net exports.

It’s All So Complicated!

So it is. It’s unfortunate, but reality doesn’t often seem to come in simple packages. Furthermore, even experienced Fed watchers are never completely sure of what Fed policymakers will do in any particular instance. However, if you can grasp the basic elements of the aggregate demand/aggregate supply model and find out how the Fed assesses the actual position of the economy, compared to its sustainable position, you will have gone a long way toward understanding how the Federal Reserve operates.