Synthenomics The Role of Financial Institutions

Post on: 7 Сентябрь, 2015 No Comment

The Role of Financial Institutions

The real world of finance is not populated by the financial traders of model fame. Numerous studies in behavioral economics have identified what appear to be deviations from fully efficient markets with rational individuals. On the individual level, we know that overconfidence leads male traders to trade much more than female traders, and this has a negative effect on their returns. Therefore agents dont seem to be optimizing — rather they have their own idiosyncratic, but systematic, biases. On the market level, stock prices seem to exhibit strong short-run momentum while also appear to have long-run mean reverting growth rates. This suggests that theres something going on with market participants that encourages overshooting in the short run but with corrections in the long run.

But what has gotten me curious over the past few months is the institutional aspect. In my view, because financial markets are actually populated by institutions that have their own quirks, financial markets can deviate from textbook models in very policy relevant ways.

Most financial models that I have read about are populated by individual investors looking to maximize some expected future consumption stream subject to various constraints. Sometimes these constraints stick to describing feasible budget allocations,and sometimes they also include cognitive biases. But Wall Street doesn’t look like this. Traders rarely trade by themselves — they are usually a part of a large firm. These firms may also have different goals. Some, such as hedge funds, are just in the business of generating pure return whereas others, such as pension funds, are looking to maintain a steady stream of payments to pay out to their customers. Given that these firms have their own institutional demands, this suggests that their trading strategies could be quite different. These structural differences has implications for market efficiency.

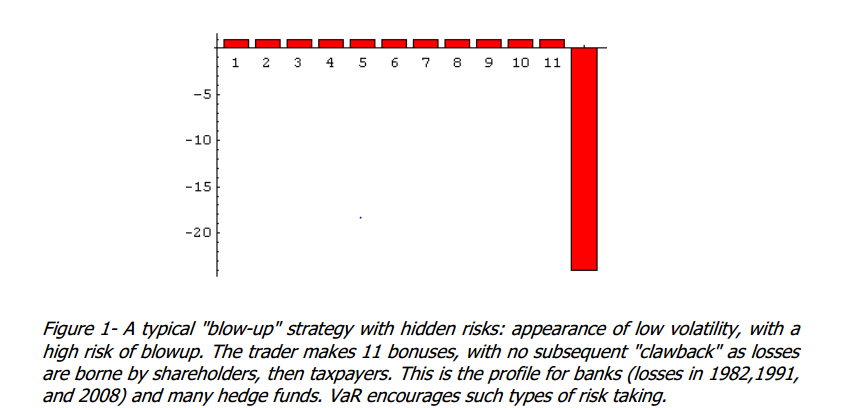

Past papers have of course addressed some of these issues. On a within-firm basis, work on the principal-agent problem has shown how compensation schemes can affect fund manager behavior. This would suggest that many financial managers maximize not the utility of the investor, but their payoff in the compensation scheme. Some past work has also indicated that institutional investors, in this case mostly pension funds, do not seem to exhibit the herding and destabilizing behavior that for which they are criticized. However, some of these benign results are being challenged in the recent financial crisis, and this could have major implications for both financial research and monetary policy.

As an example, there have been a set of recent popular articles from the Economist and FT Alphaville on the notion of VAR shocks. VAR is a measure of financial risk that (theoretically) measures the worst case outcome for a firm. For example, a 5% weekly VaR of $5 million means that there should only be a 5% percent chance that the firm will lose more than $5 million over the course of a given week. This typically can be calculated by parameterizing a loss distribution with historical data on volatility and average yields. Even though this measure can mislead by ignoring the amount that would actually be lost in a worst-case outcome its simplicity makes it a natural candidate for institutions to use as a check against overly risky trading strategies. Therefore market moves that can impact the measurement of VAR are natural candidates for making the institutional investors jump.

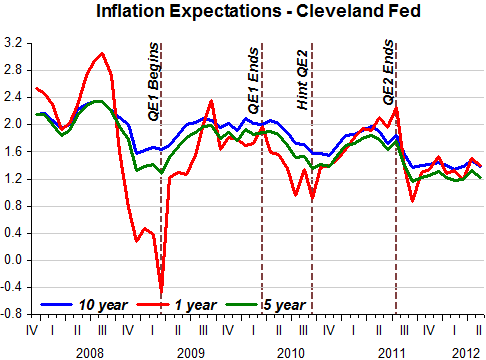

Pioneering work by Hyun Song Shin. an economist at Princeton, analyzes the role of VAR and argues that it contributes to market procyclicality. Because historical data is used to calculate the VAR that goes into risk weighting, banks may end up levering up their balance sheet just as the business cycle starts to rev up and deleveraging just as the entire cycle comes crashing down. The rising tide of the business cycle makes their VAR look much smaller, therefore allowing them to put smaller risk weights on their assets. Now that the size of risk weighted assets has fallen, banks can play the risk-weighting clause on capital requirements and fund themselves through more debt. This continues until the cycle breaks, at which point VAR measurements are shocked upward by the historical data, forcing a deleveraging in order to meet capital requirements, thereby amplifying negative effects on the business cycle. In particular, this story fits the recent financial crisis very well. Past decades of relative calm made the VAR models docile and ready for the slaughter that was 2008.

I see this as an institutional bug because theres no efficiency reason why VAR should be used in such a way to risk-weight assets. It does not make for an omniscient Q-measure to identify risk. Rather, VAR is useful because it helps institutions streamline their risk analysis. By doing so, it quite possibly improves an individual firms performance by avoiding worse evaluation methods. But with the procyclicality argument made above, it should be clear that a group of banks all using VAR to risk weight their assets end up creating severe negative externalities on the business cycle.

VAR shocks have also popped up in the Japanese case. Back in the 2003 bond yield volatility spike, many Japanese banks ended up selling bonds as the volatility triggered their VAR limits. This intensified the cycle of bond selling until other investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies bought up the bonds and stabilized the market. This serves as another real world example of Shins theory that the use of VAR in institutional settings ends up intensifying market volatility.

It should also be clear that the institutional quirks can occur in financial markets with rational arbitrageurs. If the size of institutional flows are large enough, then it may be worthwhile for the smaller traders to just ride the flows to higher returns. There may just not be enough incentive to normalize prices. If the market can stay irrational longer than individuals can stay solvent, then an individual is likely better off to just play along with the market. Given thta we see this kind of serial correlation with hedge funds in the tech bubble. the risk of individuals riding along with the irrationalities of institutions should be taken seriously. In fact, I would go far enough as to argue that the burden of proof is on those who would like to defend their financial models with only individual investors. Given that we know the real world doesnt work like that, and that this difference can result in dramatically different conclusions, the burden must on the traditionalists to show that models of individual investing can subsume those of institutions in most cases.

To measure these effects and to calibrate new models, attention should be focused on the flow of funds in and out of these institutional investments. This way we could have a better notion of relative size and be able to measure if and how much institutional procyclicality affects markets.

I see two main policy implications of this alternative approach. First, the VAR specific quirks create a further justification for strict capital requirements. Only this way can the risk weighting problem be robustly solved. In terms of monetary policy, a thorough understanding of these institutional quirks can help guide the direction of policy. As monetarism starts to integrate more markets as data points, it becomes more and more important for central bankers to know how to interpret the financial data that comes in. By knowing whats signal and whats noise, central banks can better conduct forward looking policy.