Small World Big Globe Globalization in the FinancialServices Job Market The Finance

Post on: 8 Август, 2015 No Comment

The Finance Professionals’ Post educates readers in the finance and banking sectors on the forces that shape their business. The FPP is a publication of the New York Society of Security Analysts (NYSSA).

11/01/2010

Small World, Big Globe: Globalization in the Financial-Services Job Market

Today’s job market in financial services presents a radical dichotomy. In the developed West, many jobs in banking are disappearing. Yet many of the institutions that are shrinking their workforces in New York and London continue to expand elsewhere—most visibly in Asia (particularly China) and the Middle East. Eastern Europe, India, and Latin America are benefiting, too. While comprehensive data on financial-sector job growth in emerging markets is hard to come by, a plentitude of anecdotal evidence suggests that investment banks are increasing their presence in those markets.

It’s tempting to ascribe that shift simply to the advantages to be gleaned from lower labor costs, lower taxes, and less regulation. But what is actually occurring is far more complex. At least four distinct trends are in play, set spinning by a combination of cyclical and secular forces. By and large, however, the growth of financial-services employment in emerging markets is a secular development that is likely to persist regardless of how many jobs exist in Western financial capitals. For that reason, the rise of emerging financial centers like Shanghai and Dubai is a highly positive development for Western-trained professionals who are geographically mobile.

POPPING THE MORTGAGE BUBBLE

Few of the front-office jobs that banks are slashing from their US and UK operations are moving to Asia. In large part, those cuts fall within mortgage brokerage, securitization, and other areas related to the credit bubble of the past few years. Of 189,000 announced layoffs by financial firms from August 2007 through August 2008, 86%, or 162,200, involved mortgage-related work, according to the outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas (2008).

Those jobs are simply disappearing. Some will come back after the housing sector’s next upswing. But many are gone for good. When securitization eventually revives, the process is likely to be far more measured and disciplined than it was during the bubble. Care will be paid to asset quality and cash flow, and investors will be savvier about what they’re buying. Banks’ asset-backed structuring and trading desks probably won’t regain their former proportions for a very long time, if ever.

TIMING THE CONTRACTIONS

Another bucket of job cuts is closely tied to Wall Street’s traditional businesses of advising merger deals and underwriting new issues of stocks and bonds. Cutbacks in these bread-and-butter functions repeat a familiar pattern in which jobs track deal flow, which typically hits its peaks when the cycle veers upward and overall business and financial conditions recover. That last occurred in 2005–2006, and it will come around again.

In the near term, however, bank employment in areas sensitive to the US domestic and global business cycle is poised to shrink further. As of mid-September 2008, there was little clarity on when the current cycle would bottom out. But institutions’ 2009 budgets will tend to be conservative, leery of following in the footsteps of Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, or Merrill Lynch.

A number of economically sensitive jobs are being relocated to geographies where business is more robust at the moment. As deal volumes in the US and Europe shrink, banks are transferring valued professionals out of New York and London offices with inadequate budgets. Such transfers allow an institution to retain talent within a business segment that is expected to recover. Relocations are a subject for gallows humor on some trading desks ( It’s Dubai, Mumbai, Shanghai, or good-bye ). In fact, though, the professionals who are given an option to relocate are the fortunate ones.

PILGRIMAGE TO INDIA

A third blow to US and UK professionals is the extended movement to outsource non-core functions to lower-cost locations—primarily India. This secular trend has been underway in finance for the better part of a decade.

Traditionally, outsourcing has been associated with record keeping, data processing, and call centers. It is now inching up the functional ladder to include junior-level analyst work that bears upon sell-side research reports and investment-banking pitchbooks.

WEALTH GLOBLIZATION AND GLOBAL BANKS

Wealth accumulation in emerging markets is taking place on an unprecedented level, and it is the primary long-term driver for financial-services job growth in those regions. As the money piles up, newly flush nations are discovering a lack of institutions and expertise competent to manage the growing wealth. Major global banks are picking up that slack.

These banks perceive the explosion of financial wealth in China and the Middle East (and, to a lesser extent, Russia, India, and Latin America) as a vital opportunity from both long-term and short-term perspectives. Western-trained professionals who relocate to these regions can benefit tremendously from future growth in both headcounts and advancement opportunities.

Anticipating the rapid expansion of corporate, household, and sovereign financial wealth in Asia and elsewhere, global institutions are locating a rising proportion of managing directors and other executives outside Western financial capitals. Citigroup moved Alberto Verme, cohead of its global investment bank, from London to Dubai in May 2008. Morgan Stanley’s well-known chief economist Stephen Roach moved to Hong Kong in September 2007 to become chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia.

Such high-power transfers signal the international destination’s strategic importance within a bank’s overall structure. As Western financial institutions evolve into truly global organizations, the opportunities to gain decision-making power and advancement within their outlying operations will only intensify. But these subsidiaries will frequently be headed up by Western-trained local talent.

And banks aren’t the only players whose workforce is taking on a more global footprint. Hedge funds and PE (private equity) firms are adding staff within emerging markets. Everyone is finding that in order to keep growing they must follow the money, however far from home it takes them.

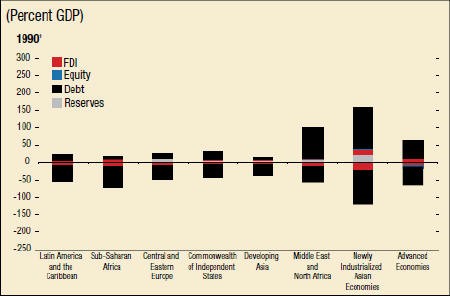

WEALTH GLOBALIZATION AND THE SWF

One manifestation of increased globalization of wealth is the proliferation of SWFs (sovereign wealth fund) with mandates to actively manage state-controlled financial assets. The largest SWFs are in Abu Dhabi, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, China, and Singapore (Beck and Fidora 2008). Many are funded by revenue from exports of oil or other commodities. As financial assets held by central banks and other sovereign institutions have ballooned, their overseers are moving away from low-returning cash equivalents—the traditional vehicle for foreign-exchange reserves—and embracing riskier asset classes such as stocks, real estate, and PE.

To manage such portfolios, the funds require experienced advisors with world-class investment expertise. Besides hiring in-house investment professionals—both expatriates and their own nationals trained within leading Western universities and financial institutions—sovereign funds are contracting for investment-management services. That generates downstream hiring by global asset-management firms, for whom SWFs represent the fastest-growing category of new customers in decades. And the funds’ need for a wide range of banking services, from trade execution to assistance with sourcing acquisitions, generates jobs within the teams of global banks that cater to this customer group.

OTHER HANDS IN THE POT

Despite all the attention, SWFs do not control the bulk of the investable wealth within their respective countries. A July 2008 European Central Bank research paper estimated the combined value of SWF assets at between $2 trillion and $3 trillion. That represents at most one-half of the total foreign-exchange reserves held by central banks (excluding SWFs), and 6% of the holdings of private asset-management firms (Beck and Fidora 2008).

Private clients make up another fast-growing business segment within emerging economies. A 2008 report from Capgemini and Merrill Lynch forecasts that the financial assets of Asia-Pacific HNW (high net worth) investors will climb from $9.5 trillion in 2007 to $13.9 trillion in 2012, surpassing the European HNW market, which is forecast to grow from $10.6 trillion to $13.5 trillion over that period. The Latin American HNW market is forecast to grow from $6.2 trillion to $10.3 trillion, a 10.8% annual pace, while the Middle East market is forecast to double to $3.4 trillion by 2012, growing 15% annually. The resulting demand is pushing up compensation for private-wealth managers, particularly in Asia.

IS THE GRASS REALLY GREENER?

The current cyclical downturn in developed markets has given Western financial institutions an additional short-term incentive to accelerate their push overseas, because emerging economies remained relatively buoyant during the initial months of the subprime credit crunch. Emerging asset markets continued to rally through the second half of 2007, while US and European stocks and bond markets weakened.

During the third quarter of 2008, however, emerging stock markets have underperformed developed markets, amid tumbling oil prices, rising systemic-risk fears, and the anticipation of worldwide economic contraction. In mid-September 2008, there were growing indications that investments in emerging markets provide less of a short-term hedge than expected against turmoil elsewhere, whether in terms of asset values or business generation. The extended suspension of trading on Russia’s stock markets during September is an extreme example.

The current global downturn has triggered significant setbacks for financial services. However, the industry has adapted to shifting conditions time and again, and it is well placed to emerge from the present cycle with renewed vigor. Over the past decade, its business mix has adapted significantly to the changing marketplace, and it will continue to evolve. Emerging markets will persevere in increasing their share of that business mix, and of the industry’s professional work force.

Beck, Roland, and Michael Fidora. 2008. “The Impact of Sovereign Wealth Funds on Global Financial Markets.” Occasional Paper Series, no. 91. European Central Bank. (July 2008).

Capgemini and Merrill Lynch. 2008. Merrill Lynch World Wealth Report 2008. (June 24, 2008).

Challenger, Gray & Christmas. 2008. “Financial Cuts Could Surpass 2007 Record” [press release and tables]. (September 15, 2008).

–John Benson is the founder and CEO of eFinancialCareers.com, a leading career site for professionals in the investment-banking, asset-management, and securities industries, covering 18 global markets.