Saviour of the euro or king of QE

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

In this section

Mario Draghi’s latest attempt to save the euro has been welcomed in some quarters and dismissed in others, writes Selwyn Parker. But will the ‘Outright Monetary Transaction’ system actually work, or end up making things worse?

It’s fair to say that Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, and Jens Weidmann, his counterpart at Germany’s Bundesbank, don’t see eye-to-eye.

‘Super Mario’, as he’s been dubbed since taking the position late last year, believes he has devised a way of saving the euro by lowering the ruinously high prices of borrowing in the financial markets by economically weak eurozone nations such as Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy. However Weidmann, remarkably young at 44 for the august Bundesbank job, fears the ECB’s actions bear a dangerously close resemblance to printing money and will do nothing to fix the underlying problems of the struggling currency.

Most authorities on the long-running travails of the eurozone estimate it will take a few months to work out which of the two protagonists is right. Meantime the Draghi solution is off and running.

Unveiled in early September, it aims to eliminate what he calls “destructive scenarios” created by severe distortions in the bond markets that have resulted from “unfounded fears” that some or all of the weak countries will have to drop out of the eurozone. The Draghi solution has three main elements. Called ‘Outright Monetary Transactions’ (OMT), it allows the ECB to step in and buy bonds from besieged nations when bond traders push their yields to sky-high, unsustainable levels.

Second, countries needing a helping hand must apply to have their bonds snapped up by the ECB. And third, a condition of that application is they will be put to the sword in austerity programmes designed to reform their economies. As Greece can vouch, these are painful.

Risk and reaction

Hardly had Draghi explained how OMT would work than the markets reacted with close to euphoria. They pushed the euro to new highs and the stock exchanges sailed out of the doldrums. Most eurozone experts expressed support, albeit qualified.

Trevor Greetham, Director of Asset Allocation at Fidelity Worldwide Investment, told the Financial Times: “The markets are right to respond positively, but intervention to lower financing costs doesn’t make the [eurozone] periphery competitive.” No, but the general consensus is that wildly erratic bond prices run the risk of tearing the currency union apart.

The only opposition

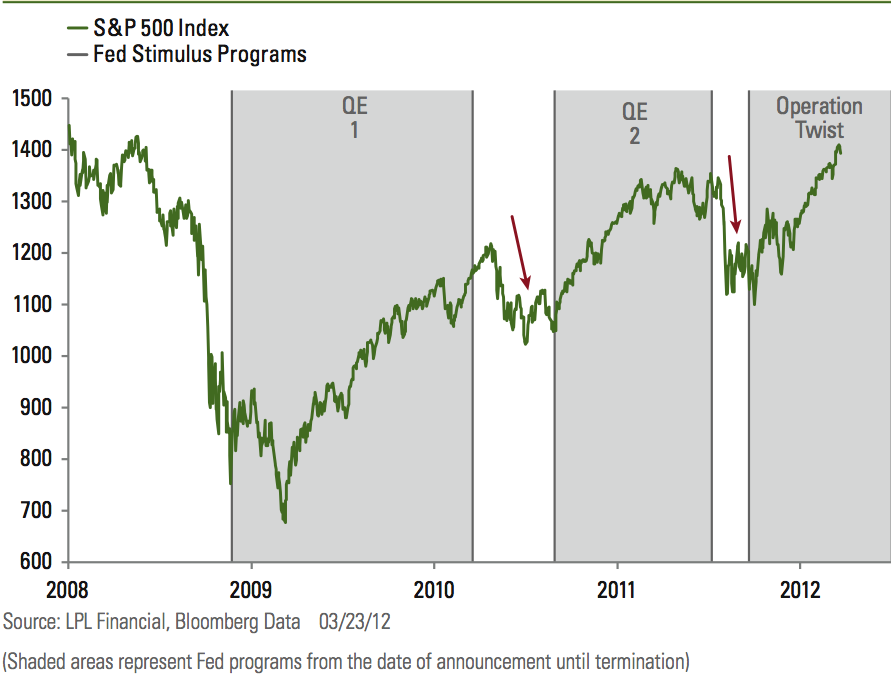

Weidmann remains unimpressed. The only member of the ECB’s governing council to oppose OMT, he insists open-handed bond buying is “too close to state financing via the money press for me.” That’s a reference to quantitative easing, the pumping of new money into the financial markets by central banks in Britain and America, in particular, to stimulate the economy. “The causes of the crisis lie in the high level of indebtedness, the lack of competitiveness of some member states and, last but not least, the lost confidence in the architecture of the monetary union,” Weidmann told Der Spiegel magazine in an interview in late August.

Bond buying is not, however, the same as printing euros. And the ECB has pledged not to increase the money supply of the eurozone, which could be highly inflationary. Germany still recoils at the memory of the hyperinflationary years of 1923, when it took a barrel of Reichsbank marks to buy a cup of coffee. “Ultimately, there will be the threat of bubbles, crises and inflation,” warns the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. We’ll know soon whether the Italian central banker has pulled off a masterstroke, or not.