Quantitative easing around the world lessons from Japan UK and US

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

The European Central Bank is poised to launch a €1tn round of quantitative easing on Thursday, years after other world central banks embarked on monetary stimulus.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke launched the US version of QE in late 2008. Photograph: DOMINICK REUTER/REUTERS

The Federal Reserve embarked on QE in November 2008 with the hope of steering the world’s largest economy through the depths of the financial crisis. When it was launched under then Fed chairman Ben Bernanke – dubbed “Helicopter Ben” for his desire to drop money out of the sky – it was, and remains, a contentious policy decision.

As the US backdrop steadily improved in the aftermath of the Fed’s cash injection, the central bank gradually slowed its bond-buying programme from $85bn a month to $15bn a month. After more than five years the Fed, now led by Janet Yellen. called time on its QE programme last October. But it committed to keeping record low interest rates for “a considerable time”.

Quantitative easing. coupled with low interest rates, freed up capital in the US and encouraged a steady rise in risk appetite, helping US shares prices to rise markedly since 2009.

QE swelled the Fed’s balance sheet enormously. Photograph: US Federal Reserve website/US Federal Reserve

US unemployment fell sharply after QE started and the US economy proved relatively solid but growth rates were patchy. The economy is forecast to grow 3.6% this year by the International Monetary Fund, which cites “continued support from an accommodative monetary policy stance, despite the projected gradual rise in interest rates.”

While the QE era in the US appears to be over, the Fed is expected to be cautious about raising borrowing costs given the slowdown in US inflation. In December, inflation was just 0.8% on the consumer price index measure, the slowest annual rate for more than five years.

The Bank of England has argued QE helped growth and the jobs market, but it also concedes the scheme did more for wealthier households. Photograph: Anthony Devlin/PA

The Bank of England launched its QE programme in March 2009 with an initial spending target of 75bn over three months. At the same time it cut interest rates to a record low of 0.5%.

Between March 2009 and January 2010 the Bank bought 200bn of assets, equivalent to about 14% of GDP to help breathe life into the UK economy following the credit crunch. Then in October 2011, faced with growing warnings of a double-dip recession and a eurozone crisis, policymakers voted to resume QE and pump another 75bn into the financial system. increasing the QE budget to 275bn.

The Bank later increased the total to 375bn. Six years on, the debate rages over whether QE was the best, or the fairest, way to steer Britain out of the credit crunch.

The Bank has faced the charge that QE has exacerbated inequality, partly by helping banks in handing them big amounts of money while doing little to support small firms and households.

The Bank itself said that wealthy families had been the biggest beneficiaries of QE thanks to the resulting rise in value of shares and bonds. But it also argued everyone had benefitted thanks to the boost to the overall economy and therefore also to jobs.

Business groups also complained that by focusing on buying government bonds rather than corporate bonds, the Bank did little for the real economy. QE did not tackle the problem of poor access to loans for small and medium sized companies struggling to stay afloat and keep on workers, they said.

But the scheme’s supporters say the economy would probably have been smaller and asset prices lower without such an unconventional loosening of monetary policy. In a paper last year, Martin Weale, a member of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee said the QE programme added about 3% or 50bn to the overall level of GDP since it was first introduced. He also suggested QE had a bigger impact on inflation than first thought and that it had a role to play in dampening stock market volatility by reducing uncertainty.

The UK economy has shown signs of slowing in recent months but it was the fastest growing of the G7 rich nations in 2014. Inflation meanwhile has fallen well below the Bank’s 2% government-set target, hitting a record low of 0.5% in December. leaving policymakers worried about the threat of deflation, of falling prices.

Japan

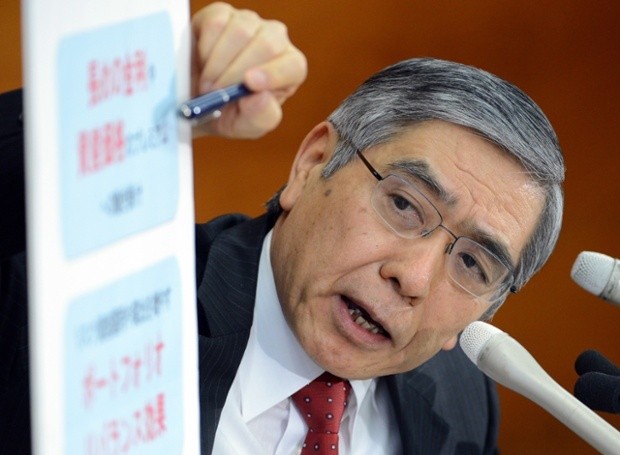

Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda has vowed to head off a return to deflation. Photograph: TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP/Getty Images

QE was effectively born in Japan, a country plagued in recent history by deflation and rolling recession. The phrase “quantitative easing” was coined to describe Japan’s efforts to kickstart growth and get prices rising again, starting in 2001 and lasting five years. That programme failed to rid the world’s third largest economy of its persistent deflation, a record that was repeatedly cited by QE’s critics as the policy was mooted in the UK and US at the onset of the global financial crisis.

The Bank of Japan’s most recent QE programme began in April 2013. when central bank boss Haruhiko Kuroda promised to unleash a massive QE programme worth $1.4tn (923bn). It formed part of a set of policies known as Abenomics. formulated by Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe. Under the QE plan, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) vowed to buy 7tn yen (46bn) of government bonds each month using electronically created money.

To put Japan’s scheme in context, the US Federal Reserve at the time was spending only a little more per month at $85bn, compared with $70bn in by the BoJ. But the US economy is almost three times the size of Japan’s.

But with inflation worryingly low and consumer spending floundering, the Bank of Japan went even further last October. In the same week that the US said it was stopping QE, Japanese policymakers revealed plans to move in the other direction and to beef up their already massive QE programme. Japan’s central bank said it would raise the amount pushed into the system each year to 80tn (447bn) from 60-70tn a year previously, mainly through the purchase of government bonds. Announcing the surprise move, Kuroda said policymakers were determined to avoid a return to deflation. “Whatever we can do, we will,” he said.

The jury is still very much out on how much QE helps ward off recession and deflation and Japan’s rocky economic record alongside its relatively vast QE scheme is seized on by critics of the policy.