Mutual Fund Categories

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

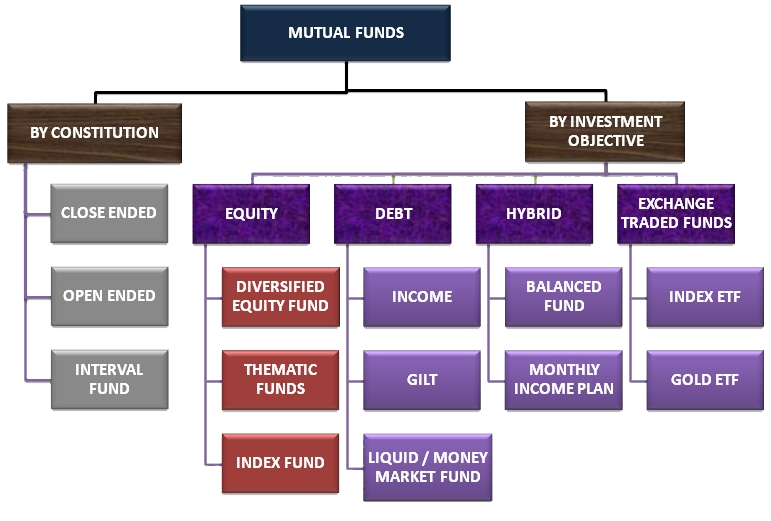

How Mutual Funds are Categorized

Mutual fund categories are defined by the classification criteria introduced in the preceding subsection. The categorization of mutual funds is a fairly straight forward task that entails blending the classification criteria in various combinations. What makes it a bit more difficult than it looks at first blush is the vast number of possible combinations. Therefore, some decisions must be made up front to limit the number of categories in the pool you choose as the universe from which you will select the funds for your portfolio. This won’t limit the total number of categories, just the number that you’ll have to consider.

If you’re already familiar with the categorization of mutual funds by type of fund, you can jump to a list of the various types of mutual funds. which has links to detailed descriptions of each type of fund.

If you look at the expanded stock mutual fund style box below, you’ll see that there are 48 distinct stock mutual fund categories defined by all possible combinations of the three primary criteria for categorizing the various types of stock funds (asset class, style and geography) and this doesn’t address the issue of the spanning of market capitalization boundaries. Pigeonholing stock funds into one of the 48 mutual fund categories is not the end of the classification process. A little more investigation is required to satisfy yourself that you have truly identified the nature of any given fund as defined by the three primary criteria.

One of the biggest reasons that many stock funds span more than one capitalization bracket is that as funds grow larger they have a hard time finding enough securities in their chosen bracket to satisfy their investing needs, so they must expand their universe into adjacent brackets.

A good example of this is small-cap funds that grow so large that they can no longer invest in just the small-cap pool because they would have to take such large positions in individual securities that their trading activities would cause significant moves in the prices of those securities. So they end up invested in the upper end of the small-cap bracket and the lower end of the mid-cap bracket, with little or no exposure to the lower end of the small-cap category and no exposure to micro-caps. If you bought such a fund when it was relatively small, you would now find that you owned an entirely different fund, although this situation probably wouldn’t be clearly stated in the fund’s prospectus, thus leaving you to make the determination on your own by investigating the breadth of their capitalization bracket.

Some funds deliberately span more than one bracket as part of their strategy. Depending on your perspective, this could cause a blurring of the mutual fund category boundaries or simply indicate that the three market capitalization brackets inadequately describe the composition of mutual funds, or both. Once again, you need to conduct a more thorough investigation to determine what size companies a fund actually is invested in. Not doing so could result in owning funds that overlap significantly with respect to market capitalization, which would result in reducing the diversification of your portfolio and increasing the correlation of your holdings, which is exactly what you should be trying not to do.

Bond funds also can be separated into many more categories than the simple 3×3 style box implies, but the additional categories for bond funds are mainly attributable to the existence of a number of major bond markets rather than the existence of additional criteria.

A look at the expanded bond fund style box below reveals that there are 78 distinct bond fund categories defined by all possible combinations of the criteria for bond funds. The expanded bond style box is actually seven 3×5 style boxes placed side-by-side to cover the seven major bond markets, and two tiers of quality have been added to the three that you’ll usually find in style boxes. Quality, duration and market are the three primary criteria.

The categorization of balanced, commodity, money market and index funds adds quite a few more categories but each of these is much less complex than stock and bond funds.

One of the most important steps in constructing your portfolio is identifying the categories that work best together to create a portfolio that is relatively efficient, i.e. has the highest expected return for a given level of risk.

Everyone in the investment management business has their own idea of what constitutes an asset class and how mutual funds should be classified. Some consider an asset class to be defined purely by the type of underlying asset. Others include investing style when defining an asset class. To the latter, large-cap value and large-cap growth are two distinct asset classes. I happen to agree with the former and recognize style as an option for the way investments within an asset class are managed. Sometimes one style will prevail over another in terms of correlation within a portfolio. At other times it is merely a matter of personal preference. I’ll discuss this further in the subsection on style.

There’s even a lot of controversy over what constitutes a well-diversified portfolio, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that disagreement exists over the classification of asset classes and the definition of mutual fund categories. The purpose of this section is to help you understand how mutual funds are categorized and give you an appreciation of what asset classes, styles and geographic exposure are available to you for constructing your portfolio.

One of the objectives in constructing a portfolio is to ensure it meets your current objectives as defined by your life situations. But to achieve this, it’s not necessary for the stated objective of every fund in your portfolio to be aligned with your objectives. Indeed, it’s very likely that you could assemble a portfolio of funds that meets your objectives and not have a single one of the funds’ stated objectives mirror your objectives. For example: Current income may be one of your objectives, but as long as the funds in your portfolio produce enough income in aggregate to meet your needs, it doesn’t really matter what the funds’ stated objectives are.

Although most systems of mutual fund categorization don’t explicitly address a fund’s objective and investing strategy, the objective and strategy should be implicit in the fund’s asset class and investing style.

As noted above, mutual fund categories are defined by three primary criteria: geography, asset class and investing style. As there are a number of subdivisions to each of the primary criteria and subdivisions to the secondary criteria, the number of possible combinations is so great that including every one of them in your portfolio would lead to over-diversification and dilution of all of the categories to the point that none would have a significant affect on your portfolio. Therefore, it will be necessary to identify the most important categories and, of those, the subset that complement each other well in terms of correlation.

Before we get down to the nitty gritty, let me give you a feel for the number of possible combinations. We’ll start at the top of the hierarchy and just consider stock funds.

First there’s geography. We have domestic, international and global. But we’ll toss out global because it’s a duplication of domestic and international. International can be broken down into the developed markets and the emerging markets, so we still have three categories at this level. The developed markets, excluding the U.S. can be broken down into various regions and even single countries. The emerging markets can be broken down similarly but the subdivision usually stops at the regional level. However, there are funds specific to Russia, China and India, all of which are large countries but whose capital markets are still emergent, thus they fall in the emerging market category. So we have dozens of options in the subdivision of the geographic category.

Now consider how stock funds are subdivided: large-cap, mid-cap, small-cap, micro-cap, sectors and indexes. Each of these subdivisions exists in each of the dozens of geographic subdivisions. The number of permutations is becoming huge, and we’re not done yet. Each of these subdivisions, with the exception of indexes, can be further subdivided by the four styles: value, growth, blend and aggressive growth. The number of permutations for stock funds is now becoming astronomical.

If you apply the same logic to real estate, commodities, bonds and money market funds, it’s obvious that this whole thing could get way out of hand. That’s why some decisions need to be made before beginning the analysis of individual funds, as it’s just not practical to do a detailed analysis within each of these low level fund categories. I have my favorites and, as you learn more and gain experience as an investor, you, too, will gravitate to a set that you are comfortable with and which meets your needs.

I’m not going to try to describe each and every combination of the criteria. What I will do in the latter subsections of this section is introduce you to the major types of mutual funds, i.e. mutual fund categories, which is what I assume drew you to this page in the first place. Just keep in mind that they can be sliced and diced a lot finer. Before getting to the specific types, I will discuss style in more depth in the next subsection, Mutual Fund Styles. and discuss the classification of stock and bond mutual funds in more detail in the two succeeding subsections.

1 2 3 4 5

Section Intro Next Section