It s Time to Fix Your Undiversified Portfolio

Post on: 30 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) is the brilliant mathematical model behind the investment concept of diversification. Nobel Prize winner Dr. Harry Markowitz introduced the theory in 1952 (1 ), and forever changed the world of finance and investing.

He proved mathematically why holding a bundle of non-perfectly correlated assets is superior to holding a few concentrated positions. He showed that by holding an appropriately diversified portfolio of assets, investors could maximize returns for any given level of risk.

I dont want to get too far into theory, because most people just dont care. And I dont want to address the underlying assumptions of MPT which have been questioned in recent years. Those things dont matter to most investors. What matters is minimizing investment risk and maximizing returns.

Any primer on Modern Portfolio Theory must begin with a recognition that investors do not like risk and need to be compensated for bearing it. Investment risk is often defined as the variation in possible returns from the average.

Higher risk investments carry a wider range of possible outcomes, but also carry higher expected returns, compensating investors for withstanding the volatility. In contrast, investments that have relatively stable returns are expected to produce lower returns.

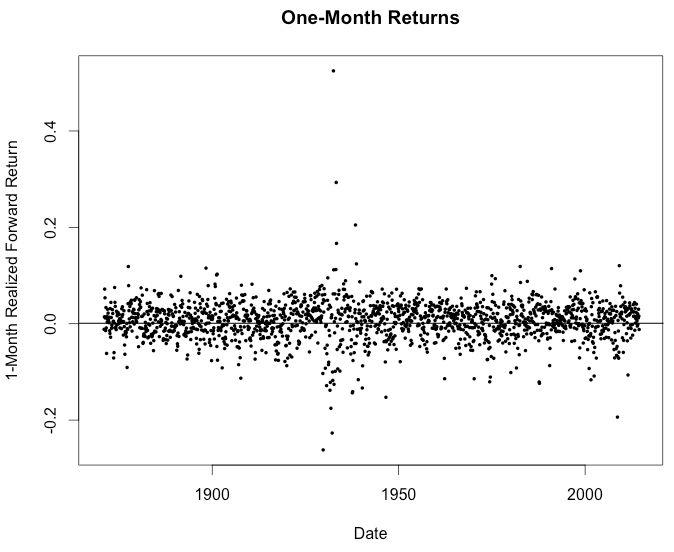

Historical data strongly supports this assumption. For example, from 1926 to 2011 the average geometric return on U.S. Treasury Bills was 3.6%. Over the same period the average return on large domestic stocks was 9.8%, while small domestic stocks returned 11.2%. This additional return is also called the equity risk premium, and is the result of the increased risk (more ups and downs) accompanying stock ownership.

Perhaps more importantly, Modern Portfolio Theory showed that not all investment risks are rewarded with higher returns. The total risk of any individual security consists of two uncorrelated components: the market, or systematic risk and the firm-specific, or idiosyncratic risk.

The entire capital market and all investors therein are exposed to unavoidable systematic risks, such as currency problems, fluctuating interest rates, war, recession, inflation, and government interventions. You cant get away from these, but you do get compensated for bearing the risk.

The idiosyncratic component simply reflects the reality that each company is exposed to a unique set of risks specific to its own business and financial situation. Idiosyncratic risk can include competition, lawsuits, fraud, bad management, financial constraints, etc. This type of risk is not rewarded, because it can be eliminated through proper diversification.

In broadly diversified indexes such as the Wilshire 5000 and the Lehman Brothers Aggregate Bond Index, idiosyncratic risk approaches zero. Investors whose portfolios are based on such broad indexes are subject only to systematic risks. By contrast, a portfolio made up of just a handful of securities, no matter how carefully researched, is subject to high levels of idiosyncratic risk. This is why stock pickers and sector investors almost always hold inefficient portfolios that underperform index investors on a risk adjusted basis.

Research

We can observe the average investors inclination to hold an undiversified portfolio quite easily in the research that has been conducted on the topic.

One excellent study on the topic, Equity Portfolio Diversification (2 ), was performed by Drs William Goetzmann and Alok Kumar. The authors analyzed the portfolio decisions of more than 60,000 individual investors at a large U.S. discount brokerage house from 1991 through 1996. In general, most investors were grossly under-diversified.

An average investor holds a four-stock portfolio (median is three).

Over-all, the evidence indicates that most portfolios have significantly higher volatility levels relative to the market portfolio, and investors are not compensated for their higher risk exposures.

In addition to widespread under-diversification, the authors find evidence to further support my argument against stock picking. If you read the arguments of many individual stock pickers, youll notice a very strong (and foolish) belief that they are somehow superior to other investors. Even though there is absolutely zero evidence supporting the idea that individuals can outperform the market over the long haul after accounting for taxes and fees, theyll argue about it. But there isnt an argument. Its fact versus myth.

Investors whose trading decisions are consistent with stronger behavioral biases exhibit greater under-diversification. Furthermore, investors who overweight certain specific industries or stock characteristics such as volatility and skewness are less diversified.

We also observe that less diversified investors trade more frequently and pay considerable transaction costs. The average annual trading cost for investors in our sample is 1.46% of their annual income. Using the brokerage data, Barber and Odean (2001) estimate that the average trading cost of active investors is 3.90% of their annual income. These transaction cost estimates indicate that investors in our sample pay considerable transaction costs but still fail to diversify appropriately.

What comes next should not surprise you. The investors who held the least diversified portfolios earned far less than the most diversified group of investors.

The unexpectedly high idiosyncratic risk in investor portfolios results in a welfare loss as measured by the Sharpe ratio of individual portfolios. This evidence in itself is not very surprising. More surprising is our finding of significant differences in the portfolio alphas. The least diversified (lowest decile) group of investors earns 2.40% lower return annually than the most diversified group (highest decile) of investors on a risk-adjusted basis. The economic cost of under-diversification is higher for the group of older investors, where the risk-adjusted performance differential between the least diversified and the most diversified investors is 3.12%

Because less diversified investors trade more frequently, these performance estimates indicate that the net returns earned by under-diversified investors are likely to be even lower. Consequently, the net performance differential between the least diversified and the most diversified investor groups is likely to be higher.

The moral of the story is this: a well diversified portfolio tends to outperform a portfolio constructed by picking stocks. In other words, own index ETFs and stop trying to buy individual stocks. Or as stated by the authors:

Most investors could have improved the performance of their portfolios by simply investing in one of the many available passive index funds.

How You Can Properly Diversify

Many investors have the wrong idea when it comes to diversification. I commonly hear people talk about buying 10-20 dividend paying, domestic blue chip stocks as a form of proper diversification. This is foolish. As is holding a portfolio comprised of 100 technology companies, or 5000 health care related companies.

These portfolios are not properly diversified. Heed the words of Dr. Markowitz on the very idea of diversification:

Not only does the E-V hypothesis (MPT) imply diversification, it implies the right kind of diversification for the right reason. A portfolio with sixty different rail-way securities, for example, would not be as well diversified as the same size portfolio with some railroad, some public utility, mining, various sort of manufacturing, etc. The reason is that it is generally more likely for firms within the same industry to do poorly at the same time than for firms in dissimilar industries. Similarly in trying to make variance small it is not enough to invest in many securities. It is necessary to avoid investing in securities with high covariances among themselves. We should diversify across industries because firms in different industries, especially industries with different economic characteristics, have lower co-variances than firms within an industry.

Proper diversification in a portfolio requires 2 components:

1) Diversification Within Asset Classes

Diversification within an asset class reduces a portfolio’s exposure to risks associated with a particular company, sector, or market.

If you want to invest in established large companies based in the U.S. you shouldnt just buy the stock of a select few. You should try to invest in as many as possible within that market segment. For example, you could just buy the S&P 500 index and own 500 of the largest domestic firms. Doing so will eliminate some idiosyncratic risk, and reduce overall volatility while providing the same level of returns.

This holds true across any asset class, not just large cap stocks. Lets take a look at Vanguards comparison of risk (volatility) between individual stocks and the average mutual fund within various asset and subasset classes.

As you can see, mutual funds have far lower standard deviation than individual securities within each asset class. This is a perfect example of Modern Portfolio Theory in action.

Continuing with our example above, instead of simply buying large domestic stocks, why not look into small company stocks and international stocks? They are still stocks, but each market segment is not perfectly correlated, which provides additional diversification benefits. Just take a look at the reduced volatility achieved by adding 20% foreign developed stocks to a portfolio comprised of the S&P 500 (large domestic stocks).

The same benefit is achieved when diversifying across sectors. Dont just buy health care stocks, buy consumer staples, and energy, and financials, and everything else that you can. Each additional sector provides additional diversification benefits.

2) Diversification Across Asset Classes

Diversification across asset classes reduces a portfolio’s exposure to the risks common to an entire asset class.

Continuing with our example above, why limit yourself to 100% stocks? You can add real estate, bonds, and cash to the mix.

Historically, the returns of most major asset categories have not moved up and down at the same time. Stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities often behave very differently at any given time. One may go up, the other may plummet. By investing in different asset classes that move up and down under different market conditions, an investor can reduce overall portfolio volatility and protect against significant losses.

For example, take a look at a portfolio that can be split between stocks and bonds.

Of course, stocks have outperformed bonds with higher volatility. But whats most fascinating is that a portfolio comprised of 100% bonds is actually less efficient that one with 80% bonds and 20% stocks. They have the same volatility, but the portfolio with stocks will achieve a higher return. This is the direct result of diversification and MPT.

Summary

Dont get lost in the details. The end result of theory and research is application, and it should be relatively easy to apply this knowledge.

Invest in broad indexes and stop trying to pick a few stocks.

In doing so, youll eliminate idiosyncratic risk almost entirely, and therefore be compensated for all of the investment risk present in your portfolio.

With low cost index providers like Vanguard, you can own tens of thousands of companies by simply purchasing a few ETFs. For example, an acceptable portfolio for the average American investor might contain:

- 40% Total U.S. Stock Market (VTI)

- 25% Total International Stock Market (VXUS)

- 20% Total U.S. Bond Market (BND)

- 10% Total International Bond Market (BNDX)

- 5% U.S. Real Estate (VNQ)

If you want to outperform the market, you can further spice things up with small cap index ETFs, value tilted index ETFs, emerging market index ETFs, etc. These investments still track an index, and are widely diversified.

But if you choose to chase excess returns, realize that you are essentially betting against market efficiency and hoping that a particular market strategy which may have outperformed in the past, will continue to outperform in the future. I wont argue with you here, but do remember that past returns are no guarantee of future returns