Investing in social change SVA Consulting Quarterly

Post on: 10 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

SVA CEO, Michael Traill explores innovative ways to build an efficient capital market for social purpose – one smart and sustainable enough to solve today’s entrenched social problems. (Based on the 2014 SVA Oration given September 2014 at NSW Parliament House.)

Michael Traill: Money isnt flowing to the right places to achieve social impact.

In 12 years at SVA, we’ve had the privilege of working with a broad spectrum of leaders, social entrepreneurs and social purpose organisations who are committed to improving the social fabric of this country. In our role as an enabler, a catalyst and a partner investing in social change, we’ve seen a lot.

We have funded over 40 high quality social ventures, drawn from over a 1000 that we’ve reviewed. We’ve directed over $45 million of funding in support of their work. We’ve advised federal and state governments on building social enterprise markets and are managing one of the country’s first social enterprise funds.

Our consulting team has completed over 550 projects with more than 300 clients including some of Australia’s largest and most respected social purpose organisations as well as government and funders. We have assisted them to determine their strategic priorities and measure their outcomes.

We were an anchor partner in the landmark GoodStart transaction, and our impact investing team has pioneered social benefit bonds in Australia and is at the forefront of building this market.

the data tells us that we haven’t made much progress on the core moral and economic issue

Through all this experience we’ve learnt a huge amount.

What has worked, and has made a difference in everything we have done, has been our ability to access capital and funding; to help identify and work with the best talent available and to be clear about the evidence of what works.

Capital. Talent. Evidence. You see these words reflected in the SVA foyer. They sit at the centre of what we do.

Figure 1: Many Australians live in a cycle of exclusion

And while SVA is not a think tank, we do think very hard about the issues and the consequences of what we see in practice. We think particularly hard about why it is that despite a generation of economic growth and in many areas quite significant funding growth, the data tells us that we haven’t made much progress on the core moral and economic issue that we face in this country – that many Australians live in a cycle of exclusion and can not fully participate in the community. Let’s focus on two unequivocal pieces of data:

- By age 15, the poorest quartile of Australian students is not only well below the OECD average, they are also nearly 2½ years behind the most affluent Australian students [1]

- There are more than 1.6 million Australians without work, or without sufficient hours of work. [2]

how do we create an efficient capital market for social purpose outcomes?

Our conclusion is simple and powerful: money isn’t flowing to the right places to achieve social impact.

The challenge is: how do we create an efficient capital market for social purpose outcomes? Because at the moment it just doesn’t exist.

What does efficient capital allocation look like?

One of the companies I have been a long term investor in is Wesfarmers. With my private equity background, I’ve always liked their long term approach to decisions about capital allocation. I also respect their consistent development of management talent and careful, high quality succession planning. When Wesfarmers acquired the poorly run Coles supermarket chain in 2007 – a controversial buy – I figured that they probably knew what they were doing. When Coles raised capital from existing shareholders in early 2008 through a renounceable rights issue, I was very happy to participate. Why? The answers were pretty clear:

- The company had a consistent track record of performance and I believed they could turn Coles around, and

- I was confident that they would identify the best quality management talent to drive the new business.

As students of corporate history will know, the company raised $2.6b from the rights issue. Wesfarmers appointed globally well-known retail executive Ian McLeod to lead the turnaround. Since then, Coles has performed very well for the group, hitting clearly defined returns targets. Wesfarmers market value has increased from $14 billion to $49 billion. [3]

If we don’t address this failure to use capital to drive success, we will be having the same discussion in 20 years time.

While the corporate world is far from perfect, it generally does a pretty good job of allocating capital, and this is a good example. Wesfarmers could readily access capital based on its track record of hitting clearly defined targets over a long period of time. Underpinning this was the company’s ability to find high quality management talent to consistently drive performance.

Capital. Talent. Evidence. It is the alignment of these that drives efficient capital allocation.

The social purpose sector presents a very different picture. If we look at the pivotal area of education and its role in generating productivity for the nation, we have conspicuously failed to allocate funding efficiently. A 3.8% real increase in spending each year from 2000-2012 (a growth of around 45% over this period) [4] has seen at best sideways performance on key global indicators, showing in the failure to improve outcomes for all students. [5]

If education was a division of Wesfarmers, it is highly likely that it would be unsuccessful in accessing further funding.

If we don’t address this failure to use capital to drive success, we will be having the same discussion in 20 years time. And in the education space alone we will have wasted a potential cumulative GDP contribution of close to 0.7% a year on Grattan Institute estimates. [6]

In the social purpose world however the motive for the allocation of capital flows is generally unclear.

The driving motivation for the allocation of capital flows in the business world is generally clear.

I invested more capital in Wesfarmers because I was driven by a desire for a clear monetary return on investment. That outcome was the desired state of my subscription to the rights issue. Capital flows in the business world are driven by clear parameters of expected financial return.

In the social purpose world however the motive for the allocation of capital flows is generally unclear.

we must be clear about the outcomes that we want capital to achieve and be able to measure them.

Of course, we understand that the challenge of measurement is different and more difficult in the social purpose world. However, we must recognise that it is the failure to be clear about desired outcomes that is the major inhibitor to effective capital allocation; desired outcomes must be the starting point for any sensible assessment of where to allocate capital. Very simply, we must be clear about the outcomes that we want capital to achieve and be able to measure them. By doing so we will create a virtuous loop so that when outcomes are achieved, we fund based on performance. And when they are not achieved, we defund and re-allocate accordingly.

We must drive a more effective and efficient capital market [7] for social purpose.

A picture of the social purpose capital market

Looking at the aggregate data about sources of capital, it is clear that the government, by orders of magnitude, is the major funder in the social purpose sector. Funding for education in schools (Figure 1) gives some idea of the relative weight of funding.

Figure 2: Government and philanthropic funding to school education [8]

More broadly, government funding is split into three components. While these include endeavours by government to mirror the performance signalling of the commercial capital markets, in practice this is very inconsistent.

government’s concern with process and probity results in a focus on the wrong measures of performance.

Social welfare services traded in the private market often benefit from business disciplines as they are set up to drive a profit, or at the very least, to break even. In some cases governments have tried to create market type competition, for example with the Job Services Network. The Job Services Network aims to provide a high quality job placement service for the unemployed. Government uses a competitive tender process to which social purpose and for profit organisations can apply. Criteria are based on the capacity to deliver sustainable job placement services.

Fee for service reflects government specifically funding the delivery of services. Frequently, however, it is the activity, not the result, that is funded. In our observation, this can lead to service organisations having a vested interest in not changing an approach which is failing to deliver real outcomes. Where is the incentive for change if government keeps funding the same service doing the same things, regardless of the outcomes it is trying to achieve?

And finally there is straight grant funding. There are areas where grant funding is more appropriate – think arts-based organisations. However, that is not an excuse for the failure to be clear about outcomes. And the failure to be clear on outcomes exposes organisations which may be doing genuinely transforming work, because in times of austerity the easiest cuts are frequently grants.

The challenges for government funding are well documented. We’ve seen and experienced many examples where government’s concern with process and probity results in a focus on the wrong measures of performance. The all too frequent result is a micro-focus on activities and what, at SVA, we call ‘busyness’ indicators. These include things like detailed quantification of the nature of programs run and numbers of people attending, together with micro-information on activities undertaken.

I learnt an early lesson on this from my colleague Kevin Robbie, Executive Director, Education at SVA, when we secured government funding five years ago to create long term employment, for people who were excluded from the job market, through social enterprise partnerships. At the time, we were still a pretty small organisation with a finance and reporting team of two people. Kevin said we would need at least another four-day a week resource to process and track the acquittals needed to secure the government funding and comply with reporting requirements. I was in disbelief – but he was right.

From the education example, we see that philanthropic funding is relatively small. We hear the argument that this private and commercially-sourced philanthropy can be flexible and strategic in ways that government struggle with. However, in truth at SVA we have seen limited evidence of this except for very small chunks of funding.

Figure 3: Funding in the philanthropic sector showing the proportion from deductible gift recipients (DGRs) and private a ncillary

I would still characterise much of the corporate and individual giving in this country as ‘spray and pray’ philanthropy – small chunks of fragmented giving based on lots of heart and not much use of head. The virtuous loop in which capital flows to high quality, well run organisations with an evidence base breaks down.

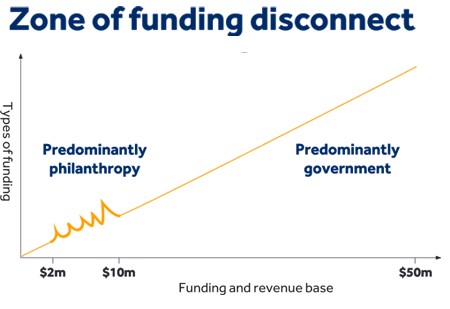

The table below highlights the core breakdowns or bottlenecks. In contrast we can look at the bright spots – the examples of positive change that paint a picture of good practice. These bright spots underpin four key recommendations that will drive much needed change in the social purpose capital market.