Ins and Outs of REIT Investing

Post on: 23 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Ins and Outs of REIT Investing

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) may offer compelling yields, but taxation can be tricky. Here�s why.

February 22, 2011

by Alan Haft

It seems like yesterday that investing in real estate held as much appeal as betting that the Minnesota Timberwolves would win this years NBA championships.

In a few short years, however, while the residential real estate market no doubt continues to show signs of weakness, the appeal of investing in various real estate sectors has once again blossomed with some interest.

While one can most certainly go out on their own and invest in real estate property by property, many people invest through something called real estate investment trusts (REITs). For those seeking income producing investments, REITs can be an attractive addition to a traditional portfolio of dividend stocks, bonds and other interest bearing investments.

With that in mind, given some newfound interest in these investments, I thought a few quick words about them would be of help to you and your clients.

What Are REITs?

REITs are essentially corporations that bundle properties and mortgages together into securities known as unit investment trusts, which are investment companies that offer an unmanaged portfolio of securities as redeemable units to investors for a specific period of time. In other words, each unit of ownership in a unit investment trust (and a REIT) represents a fraction of ownership in each of the underlying properties.

There are three types of REITs:

- Equity REITs own or rent properties. Rental income, dividends and capital gains from property sales primarily generates their revenues.

While REITs sell like stocks on the major exchange, they generate income that is competitive with bonds. Because of these unique characteristics (and their often low correlation to other asset classes), they are most often considered alternative investments.

For most individual investors, purchasing income-generating real estate is out of reach financially. REITs, however, allow small investors to pool their resources and invest in large-scale real estate projects, both residential and commercial. Additionally, many investors find REITs appealing because of their potential to produce a high level of income and their low correlation to traditional asset classes, namely stocks and bonds.

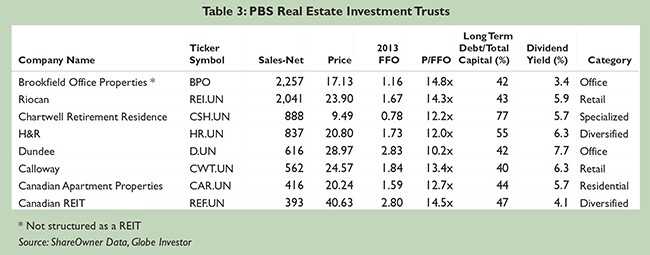

REITs are unique investments. You will get a clearer picture by looking at funds from operations (FFO) than you will by looking at net income when evaluating them from a financial perspective. This is because net income numbers include depreciation expenses, which are not often relevant to real estate because property rarely loses value and often appreciates. FFO, on the other hand, excludes depreciation and adjusted FFO also deducts the likely expenditures necessary to maintain the real estate portfolio, so this is generally a particularly good measure of the REIT’s dividend-paying capacity.

REIT Taxation 101

REITs are required by law to distribute at least 90 percent of their taxable income to their unit holders each year (and most REITs distribute 100% of their taxable income). In order to maintain their status as pass-through entities , REITs deduct these dividends from their corporate taxable income.

Since REITs are unit investment trusts, they must follow the same taxation rules as all unit investment trusts, i.e. they must be taxed first at the trust level, then at the beneficiary level.

At the trust level, REITs are subject to a few rules beyond those of other unit investment trusts.

Example: Rental income is treated as business income because the government considers rent to be the business of REITs and a result, REITs can deduct all rental-related expenses just as corporations can deduct all business expenses.

Example: Income distributed to unit holders is not taxed to the REIT, but if the income is distributed to a nonresident beneficiary, the income must be subject to a 30 percent withholding tax for ordinary dividends and a 35-percent rate for capital gains, unless the rate is lower by treaty.

More relevant to individual investors and their accountants, however, is REIT taxation at the unit-holder level. The basic rule to remember is that REITs dividend payments are taxed to the unit holder as ordinary income (at the unit holders top marginal tax rate) unless they are considered to be qualified dividends, in which case they are taxed as capital gains.

It is also important to note that a portion of the dividends paid by REITs may constitute a nontaxable return of capital. A nontaxable return of capital is a return from an investment that is not considered income; it occurs when some or all of the money an investor has in an investment is returned to them, thus decreasing the investments value.

The unit holders taxable income in the year the REIT dividend is received is reduced when a portion of the dividends constitutes a nontaxable return of capital. It also reduces the unit holders cost basis so that, theoretically, it is possible, however unlikely, for a unit holder to achieve a negative cost basis if the units are held for a long enough period of time.

That may sound complicated, so lets look at a hypothetical example. Say that Bob invests in a REIT that is currently trading at $20 per unit. The REIT has funds from operations of $2 per unit and distributes 90 percent of these funds (a total of $1.80) to unit holders. However, part of this dividend ($0.60 per unit) comes from depreciation and other such expenses, and is thus considered a nontaxable return of capital. As a result, only $1.20 ($1.80 — $0.60) of the dividend comes from actual earnings. This $1.20 is taxable to Bob as ordinary income, and his cost basis is reduced by $0.60 to $19.40 per unit. When the units are sold, this reduction in cost basis will be taxed as either a long- or short-term capital gain or loss.

REITs have performed well in recent months, with the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Developed Index, a measure of global REIT performance, returning six percent in the fourth quarter of 2010.

Early in the fourth quarter, global real-estate stocks advanced as the world economy improved. But in November, REIT markets fell when other global investment markets fell on renewed worries about troubled banks, excessive debt and rising bond yields in peripheral Eurozone countries. However, assurances from European officials calmed the markets, and UK and Continental Europe real estate stocks rebounded.

If the global economy gains firmer footing, this could bode well for real estate fundamentals and spark an investment in REITs. But following 2010s strong bounce-back for the global REIT market, its important to note that markets in the best-performing regions appear fairly valued.

Regardless of the performance of REITs in the near-term, their unique taxation of REITs can translate into compelling yields, which many investors are seeking as a consistent stream of income in todays low-interest-rate world. However, I generally recommend that REITs comprise no more than 25 percent of an investors fixed-income portfolio, as these investments are not without risks. Because they focus on one sector, for example, they can be subject to concentration risk.

Lastly, as with all investments, be sure your clients speak to a qualified tax advisor and investment advisor before making any investment.