Has quantitative easing worked

Post on: 2 Май, 2015 No Comment

Has quantitative easing worked?

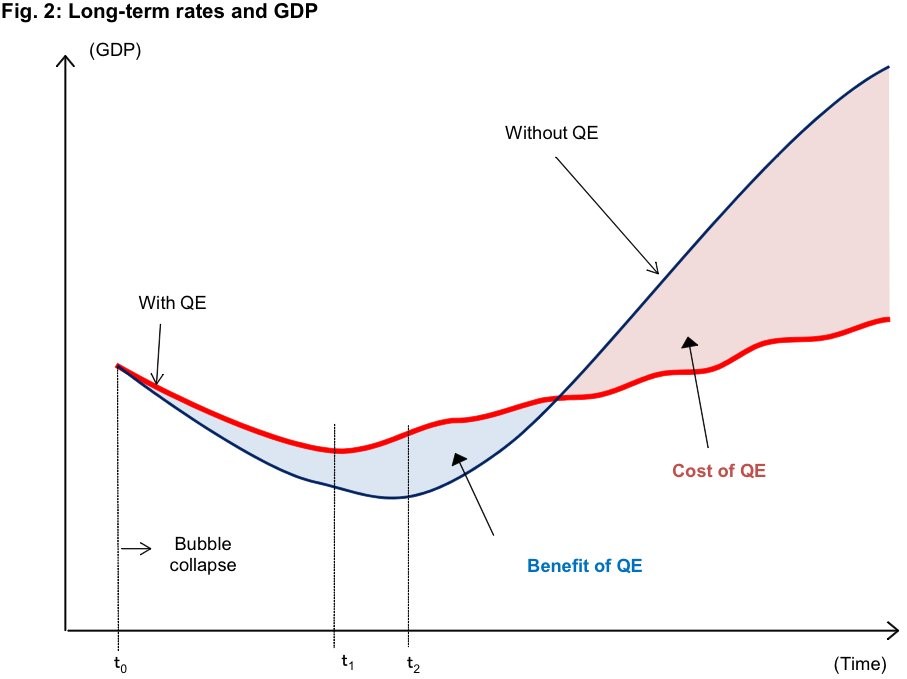

It is nearly five years since the U.S. Federal Reserve slid into quantitative easing, the deployment of artificially created money into the bond market. QE and a prolonged period of near-zero interest rates have been the highlights of post-crisis monetary policy. That era is far from over, but it has lasted long enough for a preliminary judgment of monetary policy especially as the Fed says it is now preparing to “taper” its bond purchases. My verdict: QE could have been worse, and it should have been better.

We know that policymakers might have done a worse job, because that is what they did in 1929, the last time a cross-border credit boom ended in a cross-border credit bust. Today’s central bankers have done better than their professional ancestors. In the 1930s, central bankers in many countries presided over debilitating deflation, and failed to prevent banking crises. This time, prices have neither collapsed nor exploded, and Lehman Brothers was the only big financial institution to topple.

While monetary policy helped stabilise economic and financial conditions, government bank rescues, large fiscal deficits and the automatic benefits of welfare states all played more important roles. The central banks’ support of weak institutions, and, in the euro zone, of weak governments was more important than their monetary policy.

Perhaps there would have been more financial destruction, and less productive investments, with tighter monetary policy. What can be said for certain is that QE has not worked economic wonders; growth remains slow and unemployment rates high.

Less certain, but still quite likely, is the claim that the injection of additional funds into the financial system has created new problems. The argument is simple enough. Some of the free and cheap money went to buy shares, bonds, commodities and currencies of fast-growing or high yielding economies. The new cash pushed up prices and supported unsustainably fast GDP growth in some developing nations.

It all may have looked good for a while, but now the prospect of the end of QE has abruptly reversed some of the flows. The result is wobbly financial markets and a sudden downturn in funding for countries such as India and Indonesia, which had become complacent about running large current account deficits.

So the world looks less financially stable, even as economic growth picks up a bit in developed economies. The withdrawal of QE could start another messy period in the markets.

It doesn’t add up to much to celebrate, especially considering the immense power of central banks. Surely, the monetary authorities, with the help of governments and financial institutions, could have found more effective ways to free up the global economy by cutting through the pervasive spider’s web of fear and debt? I think they need to know their limits, and have more intellectual bravery at the same time.

Humility would fight against fear. Although central bankers frequently speak about stimulating animal spirits, QE and ultra-low rates are more distressing than encouraging. They are obviously not normal, so the longer they last the greater the fear that their end will disrupt markets and the economy.

The monetary authorities adopted these policies because they overestimated the power of monetary policy to do good. No level of rates and no amount of money can deal with excesses of construction, finance or regulation. No monetary policy can train people, create jobs, build factories or change laws. Policy interest rates may help cool overheated economies or heat up unnecessarily chilly ones. Fiscal policy, however, is more effective for managing economic slumps (and booms).

After financial collapse was averted in 2009, central bankers should have set themselves more modest goals. They should have focused on keeping retail prices steady. Just that would have kept them busy enough. Success would have bred more economic confidence.

The bravery is needed to challenge traditional limits. While central bankers try to do too much, they choose to use too few tools. They have not abandoned their pre-crisis habits. They basically want to leave the financial system alone, even though volatile lending poses the greatest threat to monetary stability. They are reluctant to create and destroy money directly, even though balancing the supply of money with the supply of goods and services is the most direct way to ensure price and wage stability. And they are shy about intervening in markets, even when sharp moves in exchange rates and asset prices disrupt economies.

The respect of traditional policy limits reduced the effectiveness of QE. If the newly created money had gone directly into consumer and business bank accounts, rather than into banks, more of it would have been used to pay off excess debts or to invest productively. But at least QE was a new idea. With some more of those, central bankers could do a better job.