FRB SpeechBernanke The Chinese Economy Progress and ChallengesDecember 15 2006

Post on: 20 Октябрь, 2015 No Comment

Chairman Ben S. Bernanke

At the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China

December 15, 2006

The Chinese Economy: Progress and Challenges

The emergence of China as a global economic power is one of the most important developments of recent decades. For the past twenty years, the Chinese economy has achieved a growth rate averaging nearly 10 percent per year, resulting in a quintupling of output per person. In overall size, China’s economy today ranks as the fourth largest in the world in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) at current exchange rates and the second largest when adjustments are made for the differences in the domestic purchasing power of national currencies. This strong economic performance has resulted in improved living standards for the Chinese people. By some estimates, about 200 million Chinese have been brought out of poverty since the reforms began in 1978. 1 Moreover, by 2004 life expectancy at birth in China had reached seventy-one years, the infant mortality rate had fallen to 26 per 1,000 live births, and the literacy rate of those aged fifteen or above had reached 90 percent. 2 These are remarkable accomplishments.

Nonetheless, by most measures China remains a developing nation. 3 In particular, although life in some urban centers is typical of a modern, affluent society, average household incomes and consumption remain quite low in rural and inland areas. Thus, China faces the double challenge of sustaining a high and stable overall rate of economic growth while stimulating economic development in parts of the country that have shared less fully in the economic boom. In my remarks today, I would like to offer a few thoughts on how China can continue to prosper and promote the economic welfare of its people.

Economic progress: Markets and productivity

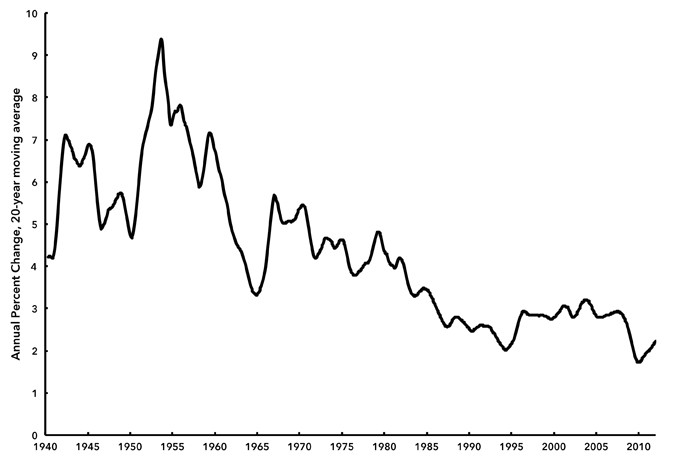

Economists agree that the most important determinant of living standards in a country is the average level of productivity, or output per worker. On this score as well, China’s record in recent decades is excellent. Between 1978, when the Open Door policy reforms began, and 1989, output per employed person in China grew vigorously, at an estimated average rate of about 6-1/2 percent per year. However, from 1990 to 2005, productivity grew at an even more impressive rate of 9 percent per year. 4

Many factors have contributed to this strong productivity performance, including high rates of capital investment, increasing openness to trade, and a strengthening of the educational system. 5 However, in my view, the single most important cause of the ongoing expansion in productivity is that China has moved, gradually but steadily, away from central planning and toward a greater reliance on markets. In 1978, almost no prices in China were determined by the market, and most production was controlled or directed by the state. Since then, the government has reduced its direct intervention in the economy and scaled back state-owned enterprises, in the process allowing more scope for market forces. By 1999, according to one estimate, about 95 percent of retail business, together with more than 80 percent of trade in agricultural commodities and producer goods, was conducted at market-determined prices. 6

Substantial experience has shown that modern economies, including those in early stages of development, are too complex to be managed effectively on a centralized basis. Prices set in free and competitive markets serve several critical functions, among them aggregating disparate information about supply and demand conditions and the relative scarcities of specific goods and services; directing resources to their most productive uses; and providing incentives to engage in cost reduction, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities.

A free market for labor is particularly critical for sustained economic development. China has made substantial progress in this area over the past few decades, most notably by reducing barriers to the movement of workers among regions, sectors, and firms and by allowing greater flexibility in the determination of employment and wages. 7 Indeed, the ongoing movement of workers from relatively low-productivity, low-wage jobs in agriculture to higher-productivity, higher-wage jobs in manufacturing and services has been a significant source of Chinese economic growth. The decline in the share of the population in rural areas, from more than 80 percent in 1970 to less than 60 percent in 2005, indicates the scale of the movement of labor out of agriculture in recent decades.

Despite these shifts, differences in labor productivity among sectors remain large. For example, in 2005, estimated output per worker in agriculture and related sectors was about $800, whereas in industries such as manufacturing, utilities, and mining, output per worker was about $5,900, more than seven times as much. 8 Moreover, a considerable portion of China’s labor force (specifically, in agriculture and in inefficient state-owned enterprises) remains underutilized. Thus, substantial additional gains in productivity for the economy as a whole might be realized through the further reallocation of the labor force to more productive and growing sectors. In particular, small- and medium-sized enterprises are emerging as an engine of job creation in China—as they are in the United States—even as they promote innovation and help to create a more dynamic and diversified economy. The government can support the process of reallocating labor to more productive uses by continuing to reduce barriers to labor mobility, helping workers obtain the education and training they need to be productive in new occupations, and encouraging entrepreneurship and small-business development.

As significant as the reallocation of labor among sectors has been, more of the improvement in productivity in recent years has resulted from increasing efficiencies within the major sectors rather than from the reallocation of resources between sectors. Here again, markets and competition have played a vital role. In particular, the opening of the economy to international trade and investment, which has accelerated since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, has done much to harness market forces in the service of the country’s development. Exposure to the competition of the global marketplace has forced Chinese producers—alone or in partnership with foreign firms—to increase their efficiency and improve the quality of their output. Notably, globally-engaged firms (or their affiliates) operating in China have helped to foster productivity growth in the country by introducing new technologies and managerial techniques, as well as by enhancing domestic competition.

Although the expansion of the market-based portion of the economy has yielded impressive results, further gains could be achieved by allowing still greater scope for market forces. The energy sector presents one such opportunity. As you know, China’s appetite for energy has grown rapidly: China’s consumption of oil has risen by more than 50 percent since 2000, and the International Energy Agency estimates that Chinese oil usage has increased by about 400,000 barrels per day in 2006, representing nearly half of this year’s growth in world oil demand. This rapid expansion in energy use reflects both overall economic growth and a relatively energy-intensive pattern of development. Greater use of market pricing in the energy sector, including the elimination of remaining price controls on fuels and the liberalization of electricity prices, would support cleaner, sustainable economic growth by promoting more-efficient use of energy by households and firms and by encouraging the development of new energy supplies. 9

Significant benefits could also be obtained by allowing a larger role for market forces in guiding investment decisions. China’s economic growth owes much to the extraordinary share of GDP that is devoted to investment in new capital, such as factories, equipment, and office buildings, which is partly financed by a very large amount of business saving. 10 However, the rapid pace of investment growth raises concerns about whether new capital is being deployed in the most productive ways. In particular, some analysts have questioned whether China is getting an adequate return on its investment. For example, from 1990 to 2001, fixed investment as a share of GDP in China averaged about 33 percent, and the economy grew at an annual rate of 10 percent. Between 2001 and 2005, fixed investment’s share of GDP rose to about 40 percent, but the economy’s average growth rate remained about the same, suggesting a lower return to the more recent investment. Comparisons can also be drawn to the rapid development phases of other Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan. Average annual growth was between 9 and 10 percent in South Korea during the 1982-91 period and in Japan during the 1955-70 period; but for both countries during the relevant years investment’s share of GDP was about 30 percent, lower than it is in China today. In a few Chinese industries, heavy investments have continued even as signs of excess capacity have begun to appear—another possible indication of capital misallocation. An example is the steel industry, in which excess capacity appears to have tripled between 2002 and 2005 to reach more than 115 million metric tons. 11 Allowing competitive financial markets to play a larger role in the allocation of capital would likely increase the returns to investment and reduce the risk that uneconomic investments could exacerbate the problem of nonperforming loans and contribute to future financial instability. Basing investment decisions on market signals also takes better account of the costs of inputs complementary to capital, such as labor (relatively abundant in China) and energy (relatively scarce). 12

China has taken initial steps toward a greater reliance on markets for determining the allocation of investment—for example, by authorizing and beginning to liberalize the stock market. China has also strengthened its banking system by improving supervision, confronting the enormous problem of nonperforming loans, allowing domestic institutions to partner with foreign banks, and increasing the use of market-based criteria in bank lending. These trends are positive; however, a great deal more remains to be done, including broadening the range of financial instruments available to savers and borrowers; taking further steps to ensure that credit evaluation and extension are based on sound economic criteria; increasing competition in banking and finance; improving credit availability for consumers and smaller firms; removing the remaining controls on interest rates; and eliminating the use of quantitative and administrative measures to influence the amount and composition of capital investment. Finally, capital markets require an appropriate institutional foundation to function effectively: Well-defined property rights (including intellectual property rights), transparent accounting standards, good corporate governance, effective supervisory oversight of banks and markets, the consistent enforcement of contracts, and rules that allow for orderly bankruptcy proceedings for unprofitable firms all help to support efficient investment. China has made progress in developing these critical institutions, but continued focus on these areas would provide large economic benefits in the long run.

Macroeconomic policy

Moving from microeconomics to macroeconomics, I believe that China could benefit by improving its tools for managing the economy—notably, monetary and fiscal policies. Effective use of macroeconomic policy tools can help achieve low and stable inflation and increase economic stability by moderating the effects on growth of temporary fluctuations in global or domestic demand. Stable economic conditions reduce an important source of risk and consequently promote innovation and growth. As a central banker, I will focus my remarks on the development of monetary policy. 13

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the nation’s central bank, is capable and well-respected around the world. However, monetary policy can work well only to the extent that financial markets are sufficiently developed to allow the monetary authorities’ interest-rate decisions to affect economic activity in a reasonably predictable way. The development of a reliable monetary transmission mechanism is thus another reason to reform and strengthen China’s banks and financial markets. The more interest-sensitive that borrowing and investment decisions are, the more monetary policy can affect investment and aggregate demand without the need for quantitative controls. Moreover, when funds are allocated on market principles, only those projects with an expected risk-adjusted return that is higher than the relevant market rate of interest will be undertaken. Thus, for example, if the central bank raises interest rates, the market will ensure that the resulting slowing of investment will be borne by the least promising projects, without the need for officials to make such judgments.

The effectiveness of monetary policy would also be enhanced by greater flexibility in the exchange rate. To maintain the current close link of the renminbi (RMB) to the dollar in the presence of capital inflows (arising from China’s trade surplus or from foreign purchases of RMB-denominated assets), the PBOC must intervene in the exchange market to buy dollars with RMB. Increases in the domestic money supply will result unless the central bank offsets the effects of these purchases on the money supply by selling bonds to investors, primarily commercial banks, in exchange for RMB—a procedure commonly referred to as sterilization. If dollar purchases by the central bank were not routinely sterilized, the money supply might increase more than desired, possibly leading to an overheating of the economy and inflation.

To date the PBOC has been largely successful in its sterilization operations, but if it continues to use this strategy it will eventually encounter problems. If the exchange rate and the domestic interest rate are maintained near their current levels, the incentives for capital inflows—and thus the need for continued intervention and sterilization—will remain undiminished. Accordingly, the value of outstanding sterilization bonds will continue to grow rapidly. These bonds could substitute for other assets that might be held by banks and private investors, potentially interfering with the growth and development of private financial markets. Further, the perception that the RMB is undervalued (a point to which I will return) has fueled additional capital inflows, as investors expect to earn capital gains when the RMB ultimately appreciates. However, these speculative inflows only increase the need for exchange-market intervention and sterilization.

In the longer term, the continued growth and modernization of the Chinese economy will require a substantial loosening of current restrictions on the flow of financial capital into and out of the country. However, if fluctuations in the value of the RMB remain limited within a narrow range, permitting substantial capital mobility would almost entirely eliminate the PBOC’s capacity to use monetary policy to stabilize the domestic economy, as any excess of Chinese over dollar interest rates, for example, would trigger large capital inflows. Further appreciation of the RMB, combined with a wider trading band and with the ultimate goal of a market-determined exchange rate, would allow an effective and independent monetary policy and thereby help to enhance China’s future growth and stability.

From an institutional perspective, China may find—as many countries have done— that granting greater autonomy to the central bank, by insulating it to a degree from short-term political concerns, increases its ability to ensure price stability and support stable growth. Of course, central banks must remain accountable to governments over the longer term.

Trade, capital flows, and the transition to domestically-led growth

A central component of China’s development strategy has been its openness to trade and capital inflows. For example, the value of goods exports and imports currently equals about two-thirds of China’s GDP, a high level for a country of China’s geographic size. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) has been particularly effective in stimulating trade: Since joining the WTO in 2001, China has seen the dollar value of its exports grow at an average rate of about 30 percent per year, compared with annual growth of about 12-1/2 percent over the five years before gaining WTO membership. China currently accounts for about 7-1/2 percent of world exports, up from 1-1/2 percent in 1985. About half of China’s trade is so-called processing trade; that is, components and materials are imported (mostly from other Asian countries), processing or assembly is done in China, and the finished product is re-exported. Much economic research has shown that openness to trade promotes growth. 14 Trade supports growth not only through the classical principle of comparative advantage, but also through the effects of trade on the intensity of market competition, transfers of technology and knowledge, and other factors.

China has also proved successful in attracting capital inflows, particularly foreign direct investment (FDI). The flow of FDI into China increased from about $2 billion in 1986 to $72 billion in 2005, making the country the third largest recipient of FDI in the world, after the United Kingdom and the United States. 15 FDI benefits China’s development by bringing with it new technologies, products, and business methods. 16 The flow of foreign investments in Chinese securities has also increased significantly, reaching $22 billion in 2005.

As you know, China today is running substantial trade and current account surpluses. These external surpluses are caused in part by China’s remarkably high saving rate. 17 Because China’s national saving rate is even higher than its rate of domestic investment, the country has excess funds to lend in the global capital market; it follows from the balance-of-payments accounts that China’s net lending abroad (or its acquisition of foreign assets) equals the country’s current account surplus. A large portion of this lending finances foreigners’ purchases of Chinese net exports (the trade surplus). High household saving and the corresponding low level of consumption in China contribute to the trade surplus by depressing the demand for imports and by forcing domestic firms to look abroad for markets.

Together with the large trade and current account deficits of the United States, the Chinese external surpluses are contributing to the current pattern of global imbalances, which many economists and policymakers have argued are unsustainable in the long run. The Chinese leadership has recognized the importance of encouraging imports and achieving greater balance in China’s international trade, having recently included these objectives in the Five-Year Plan for 2006-2010. In my view, not only would China’s achieving smaller external balances contribute to global financial stability, it would also be in China’s economic interest.

Although China’s extensive participation in the global trading and financial systems has been invaluable for the country’s development, the ultimate purpose of economic growth is to improve living standards at home. Today, about half of China’s GDP is devoted to investment and to producing net exports for the rest of the world, and thus only the remaining half is available for consumption, including government consumption. In particular, household consumption in China last year was only 38 percent of GDP, down from 45 percent in 2001. In comparison, household consumption was about 60 percent of GDP in India in 2004, according to the most recent available data. China’s low share of consumption in GDP is, of course, the counterpart of its high national saving rate.

Policies aimed at increasing household consumption would clearly benefit the Chinese people, notably by improving standards of living and allowing the fruits of economic development to be shared more widely. Such policies, by reducing saving and increasing imports, would also serve to reduce China’s current account and trade surpluses. 18 Putting greater reliance on domestic demand rather than net exports to drive growth would also decrease China’s vulnerability to fluctuations in global demand.

How can China direct a greater share of its output to domestic consumption? Again, increased flexibility in the exchange rate could help. As the Chinese trade surplus has continued to widen, many analysts have concluded that the RMB is undervalued. 19 Indeed, the situation has likely worsened recently; because of the RMB’s link to the dollar, its trade-weighted effective real exchange rate has fallen about 10 percent over the past five years. 20 Allowing the RMB to strengthen would make imports of consumer goods (as well as capital goods) into China less expensive. Greater scope for market forces to determine the value of the RMB would also reduce an important distortion in the Chinese economy, namely, the effective subsidy that an undervalued currency provides for Chinese firms that focus on exporting rather than producing for the domestic market. A decrease in this effective subsidy would induce more firms to gear production toward the home market, benefiting domestic consumers and firms. Reducing the implicit subsidy to exports could increase long-term financial stability as well: If China invests too heavily in export industries whose economic viability depends on undervaluation of the exchange rate, a future appreciation of the RMB could lead to excess capacity in those industries, resulting in low returns and an increase in nonperforming loans.

Although more flexibility in the exchange rate would be helpful, the most direct and probably the most effective way to reduce the external surpluses and increase the welfare of Chinese households is to take measures to reduce domestic saving relative to domestic investment. 21 Why is domestic saving so high at present? The high saving rate of households, even very poor households, likely reflects the relatively thin social safety net in China. For example, only about 14 percent of the population is covered by health insurance, and pension plans (which, in any case, replace only about 20 percent of pre-retirement earnings) apply to only about 16 percent of the economically active population. 22 Combined expenditures by the central government and local governments on education, health, pensions and relief, and social security amount to only about 4 percent of GDP, lower than most other countries at similar income levels. In the absence of a stronger social safety net, Chinese households save at high rates to protect themselves against risks such as unexpected medical expenses and poverty in old age.

A sustained program of expanding social services has the potential for reducing saving and raising living standards in China and, at the same time, moderating China’s external surpluses. In particular, increased government spending on health, education, and other types of social services would raise both household consumption and government consumption, and thus reduce national saving. As one means of helping to fund the increase in social expenditures, state-owned enterprises could be required to pay larger dividends to the government, a measure which I understand to be currently under consideration. Financial reforms that increase the access of households to mortgages, private insurance, and other forms of consumer finance would also support higher rates of consumption.

As I have noted, the Chinese leadership has made reducing the trade and current account surpluses an important policy objective. Further, recognizing that achieving these goals would be greatly facilitated by increases in consumption and in the social safety net, the government has instituted or proposed various reductions in taxes and increases in social spending. The government has also announced an effort to raise living standards in rural and inland areas. Obviously, it is too early to judge the success of these initiatives. However, these efforts are constructive and deserving of support.

Conclusion

As I have discussed today, China has made remarkable economic progress since the reforms began in 1978. Greater use of markets, together with expanding trade and capital flows, has helped to increase growth in output and productivity, which in turn has increased living standards significantly. A still-greater reliance on markets, particularly for allocating capital investment, would contribute to a continuation of strong economic growth. Further development of macroeconomic policy tools would also support healthy growth by keeping inflation low and by increasing economic stability.

China also faces some significant risks and imbalances. The principal risk arises from the likelihood that capital is not being allocated as efficiently as possible, the result of an undervalued exchange rate and of capital markets that, despite positive steps, remain distorted and underdeveloped. Misallocated capital will not pay the highest possible returns, leading potentially to slower growth and future financial stress. In addition, monetary policy may be constrained by the lack of a reliable monetary transmission mechanism and by the relative inflexibility of the exchange rate, which inhibit the central bank’s ability to keep inflation low and to stabilize the economy.

The principal imbalance lies in the composition of Chinese GDP, which is heavily tilted toward investment and net exports and away from domestic consumption and government provision of social services. A better balance would improve the welfare of the Chinese people (by increasing consumption and social services) and would increase global financial stability (by reducing China’s current account and trade surpluses). The Chinese government has undertaken to reduce this imbalance by taking measures to expand domestic demand, especially household consumption, and I hope that these efforts will be successful.

China’s development and its opening up to the global economy have also benefited the United States in many ways. China is now the second-largest source of U.S. imports; these imports boost U.S. real incomes by allowing U.S. households to purchase consumption goods and U.S. firms to purchase intermediate inputs at lower cost. China is also a growing market for investment and exports by U.S. firms. Since China joined the WTO, U.S. exports to China have more than doubled. As China develops further, its households and firms will demand a greater variety of goods and services, enhancing opportunities for producers in industrial countries, including the United States. At the same time, trade—with all its benefits—does displace some workers and firms as patterns of production and consumption change. The policy challenge for the United States is to help those who are adversely affected by trade while preserving the broad gains that openness to trade provides for the economy as a whole.

The economic relationship between China and the United States is of extraordinary importance, and both countries have much to gain from interactions with each other. Serious challenges exist as well, requiring both countries to address such areas as energy, the environment, intellectual property rights, and global imbalances. Regarding global imbalances, I have discussed means by which China can reduce its contribution to the imbalances while encouraging domestic consumption. The United States must also do its part, in particular by increasing its own rate of national saving and by avoiding protectionism. With greater integration come greater interdependence and greater responsibility. I hope that our countries will work together in a spirit of cooperation to address these shared challenges.

Anderson, Jonathan (2006). The Complete RMB Handbook , 4th ed. UBS Investment Research, Asian Economic Perspectives, September.

Bergsten, Fred C. Bates Gill, Nicholas R. Lardy, and Derek Mitchell (2006). China, The Balance Sheet: What the World Needs to Know Now about the Emerging Superpower. New York: PublicAffairs.

Brooks, Ray (2004). Labor Market Performance and Prospects, in Eswar Prasad, ed. China’s Growth and Integration into the World Economy: Prospects and Challenges. Washington: International Monetary Fund, pp. 51-61.

Dunaway, Steven, Lamin Leigh, and Xiangming Li (2006). How Robust are Estimates of Equilibrium Real Exchange Rates: The Case of China , IMF Working Paper 06/220. Washington: International Monetary Fund, October.

Frankel, Jeffrey A. and David Romer (1999). Does Trade Cause Growth? American Economic Review. vol. 89 (June), pp. 379-99.

Goldstein, Morris (2004). Adjusting China’s Exchange Rate Policies, paper presented at the International Monetary Fund’s Seminar on China’s Foreign Exchange System, held in Dalian, China, May 26-27.

Goodfriend, Marvin, and Eswar Prasad (2006). A Framework for Independent Monetary Policy in China , IMF Working Paper, 06/111. Washington: International Monetary Fund, May.

Hoffman, Bert, and Louis Kuijs (2006). Profits Drive China’s Boom, Far Eastern Economic Review. vol. 169 (October), pp. 39-43.

Kuijs, Louis (2005). Investment and Saving in China , World Bank Policy Research Paper 3633. Washington: World Bank, June.

__________ (2006). How Will China’s Saving-Investment Balance Evolve? World Bank Policy Research Paper 3958. Washington: World Bank, July.

Lardy, Nicholas R. (2002). Integrating China into the Global Economy. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

___________ (2006). China: Toward a Consumption-Driven Growth Path , Policy Briefs in International Economics, P806-6. Washington: Institute for International Economics, October.

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006). China Statistical Yearbook. 25th ed. China Statistics Press.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. and Andrew M. Warner (1995). Economic Convergence and Economic Policies, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1995:1, pp.1-95.

Shan, Weijian (2006). The World Bank’s China Delusions, Far Eastern Economic Review. vol. 169 (September), pp.29-32.

Wacziarg, Romain (2001). Measuring the Dynamic Gains from Trade , World Bank Economic Review. vol. 15 (September), pp.393-429.

World Bank (2006). On-Line China Country Profile, World Development Indicators. www.devdata.worldbank.org/wdi2006/contents/home.htm.

Zebregs, Harm (2002). Foreign Direct Investment and Output Growth, in Wanda Tseng and Markus Rodlauer, eds. China: Competing in the Global Economy. Washington: International Monetary Fund, pp. 89-100.

1. Bergsten and others ( 2006), p. 3. Return to text

3. For example, according to 2005 data from the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook database, China’s per capita GDP is about one-sixth of that of the United States on a purchasing-power-parity basis and about one twenty-fifth that of the United States at current exchange rates. Return to text

4. Productivity growth rates are calculated by Federal Reserve Board staff using Chinese data on output and employment. Productivity can be difficult to measure, and so these figures should be treated as approximate. A new method for surveying employment was introduced in 1990, resulting in a break in the series in that year. Return to text

5. See, for example, chapter 2 of Bergsten and others (2006) for a discussion of why China has grown so rapidly. Return to text

7. Brooks (2004) provides details of some of the labor market developments in China in recent years. Return to text

8. Calculations use current exchange rates and are based on output and employment data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China and the Chinese State Statistical Office; most data from Chinese national sources are obtained from the CEIC database. Return to text

9. The adverse effects on poor households of eliminating price controls on fuels would best be dealt with through direct cash grants. Return to text

10. World Bank researchers have concluded that business saving now finances the majority of business investment in China (Kuijs, 2005). Some have questioned this (Shan, 2006). For a discussion of the issues involved in the debate, see Hoffman and Kuijs (2006). Return to text

11. Based on production and capacity data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics. Return to text

12. Market-based allocations of capital do not take into account environmental and other external effects, unless additional mechanisms such as tradable pollution permits are employed. Return to text

13. Goodfriend and Prasad (2006) provides a good description of the banking and financial systems of China and of issues regarding the implementation of monetary policy. Return to text

14. See, for example, Sachs and Warner (1995), Frankel and Romer (1999), and Wacziarg (2001). Return to text

15. In 2005, the United Kingdom surpassed both China and the United States as the largest recipient of FDI in the world. In 2004, China ranked second after the United States. Return to text

16. For a discussion of the relationship between FDI and economic growth in China, see Zebregs (2002). Return to text

17. China’s national saving rate was 41 percent in 2003 and 47 percent in 2005, according to IMF figures. As of 2003, the latest date for which detailed data are available, households accounted for 42 percent of domestic saving, with firms (including state-owned enterprises) and government accounting for 36 percent and 22 percent of domestic saving, respectively (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2006). Return to text

18. See Lardy (2006), for example, for a careful discussion of the need for reorientation of Chinese growth toward consumption. Return to text

19. See, for example, Goldstein (2004) and Anderson (2006). Dunaway and others (2006) provide a useful analysis of the sensitivity of the Chinese equilibrium real exchange rate to alternative approaches and assumptions commonly used. Return to text

20. The estimate is by Federal Reserve Board staff for the period from November 2001 to November 2006. Return to text

21. Kuijs (2006) documents the sources and composition of saving and investment in China. Return to text

22. Bergsten and others (2006), p.28. Return to text