Exporting Financial Instability

Post on: 30 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Activists wave Malaysian flags during a protest against Trans-Pacific Partnership ahead of U.S. President Barack Obama’s Malaysia visit, outside the U.S. Embassy in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Friday, April 25, 2014.

T he late Dr. Martin Luther King is praised for saying “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Along the same lines, if we learned anything from the global financial crisis it is that financial instability anywhere is a threat to financial stability everywhere.

The Obama administration appears not to have learned that lesson. The trade treaty agenda announced at the State of the Union address is an injustice that will rob our trading partners of the ability to prevent and mitigate a financial crisis. That could not only spell instability for our trading partners, but for the U.S. economy as well.

At the State of the Union, Obama asked the Congress to grant him the authority to finish the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—a trade and investment treaty with a number of Pacific Rim countries including Peru, Chile, Mexico, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Japan, and others. Given that the United States has trade treaties with the majority of those countries, the projected gains of the treaty are a tiny three-tenths of 1 percent of GDP in 2025. Members of Obama’s party have not been supportive of the bill because those small gains would be met with high costs for workers and regulations in the United States.

One of the measures on the TPP agenda that is a cause for concern is that the treaty would deem it illegal to regulate international financial flows among the parties to the agreement.

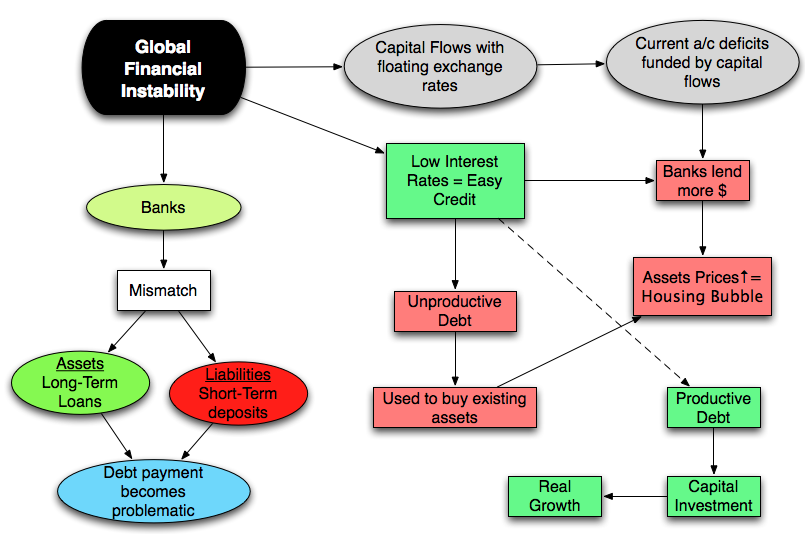

As we saw during the financial crisis, the crisis went global because of the interconnectedness of strong and powerful global banks. U.S. banks both lent and borrowed large sums to and from other banks and corporations around the world. When the financial services firm Lehman Brothers fell, balance sheets shivered from New York to Santiago to Greece and beyond.

U.S. attempts to recover from the crisis also impacted the rest of the world. In the absence of a strong enough fiscal stimulus package in the U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Benjamin Bernanke kept short- and long-term interest rates low and embarked on a policy called quantitative easing (QE), purchasing mortgages and other securities, to stabilize asset prices and repair banks’ balance sheets. These Fed policies were intended to get banks back to lending to people, to U.S. factories, small businesses, homes, and more. But until recently, banks wouldn’t lend because there was too little demand in the U.S. economy to support such activity.

Instead, global banks played the carry trade. The carry trade is an investment strategy in which a financial actor, usually a hedge fund, borrows dollars at low interest rates and then invests them in a country with a higher interest rate—emerging markets like Brazil, India, and others in this case. The difference between the two interest rates is the carry, or the first bit of profit an investor can make.

This is exactly what happened in the wake of the global financial crisis. From 2009 to 2013, countries including Brazil, South Korea, Chile, Colombia, Indonesia, and Taiwan all had lucrative interest-rate differentials and experienced massive surges of capital flows. The interest-rate differential between Brazil and the United States was more than 10 percentage points for a while. It’s little surprise that New York hedge funds saw a better bet in Brazilian bonds than investing in the housing market in Nebraska or factories in Ohio. The result was significant currency appreciation—as much as 40 percent in Brazil from 2009 to 2011—and asset bubbles in real estate and stock markets. The same was true in other countries across the developing world.

A few countries rose to the challenge and put in place new regulations to stem financial instability stemming from U.S. financial flows. As I show in my new book, Ruling Capital: Emerging Markets and the Reregulation of Cross-border Finance . two examples are Brazil and South Korea. Both countries invented innovative regulations on foreign exchange derivatives after the crisis in an attempt to stem the harmful impacts of short-term inflows. The measures taken by South Korea have proved to be more effective because there were more stringent and in an environment where derivatives markets were over-the-counter and deliverable. Brazil’s regulations had some positive impacts, but were relatively timid and more easily circumvented through Brazil’s offshore markets that are harder to regulate.

But if these surges of capital inflows seem bad, the reverse is even worse. And that’s what emerging markets are bracing for now. According to the latest estimates by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), emerging markets now hold a staggering $2.6 trillion in international debt securities and $3.1 trillion in cross-border loans—the majority in dollars. As U.S. interest rates creep up over inflation hypes, that money is being sucked out of emerging and developing countries and into the U.S.—causing their currencies to depreciate, inflating the amount of debt that is owed by corporations and government, and contributing to the emerging market slowdown.

New thinking in the economics profession and a push by the BRICS countries at the IMF even moved the IMF—which had traditionally shunned cross-border financial regulation—in 2012. The IMF has a new institutional view. which recognizes that countries need to regulate capital flows. When hot money is pouring in, countries need to regulate the inflow in order to avoid massive currency appreciation and asset bubbles. When money is fleeing out, nations need to regulate outflows to stem the fall in their currencies and the bloating of balance sheets. As I document in my book, to those ends, the IMF endorsed Brazil and South Korea’s efforts, and even required that Iceland regulate capital flows as part of its plan to rescue that country.

Although the U.S. (which has veto power at the IMF) endorsed the new IMF view, it has failed make this view consistent with its own trade and investment treaties. The IMF itself has noted that in terms of trade and investment treaties “these agreements in many cases do not provide appropriate safeguards.”

What is worse, U.S. treaties allow big banks the right to directly sue foreign governments over these regulations in closed-door tribunals—unlike disputes at the World Trade Organization (WTO) that occur among nation-states and are relatively more open.

S ome in the U.S. Congress have been pushing back. Barney Frank, then a U.S. congressman from Massachusetts, and others held hearings in 2003 when the Bush administration’s trade deals outlawed the regulation of capital flows. Shocked that a president of his own party was to do the same, before he left office, Frank engaged in a series of debates with the Obama administration where he tried to get Obama’s team to take a sounder route.

Now Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts is leading the charge in the United States Senate. In December the senator wrote a letter to the United States Trade Representative Michael Froman. Warren said she would “oppose the inclusion of terms in the TPP” that could limit the ability of governments to regulate capital flows.

In separate notes this January, Warren was dismissed by Froman and by by Jeffrey Zeintz, director of the National Economic Council, in the same manner their offices rebuked Congressman Frank in the past. Each made vague assurances that “the president will not allow this agreement to undermine essential financial reforms.”

That’s not what the U.S. is telling its trading partners. Chile has asked for an exception for its noted Encaje law that allows the Chilean central bank to regulate the inflow of capital in order to prevent crises. Malaysia and other countries have asked for a balance of payments exception that would allow nations to regulate the outflow of capital in an emergency—as Malaysia did after the Asian Financial Crisis.

Yet under the TPP, our negotiating partners have been repeatedly told that the U.S. will not expand the existing exceptions for prudential measures in our treaties in order to grant countries the flexibility to regulate capital flows. The U.S. also refuses to include a balance of payments exception in the TPP that would allow nations to deploy Malaysian or Iceland-like regulations in an emergency. The U.S. endorsed such exceptions in the WTO and in NAFTA, but the U.S. doesn’t appear to view TPP nations in the same regard.

Limiting the ability of our trading partners to regulate financial flows may benefit a few big banks and hedge funds in the short-term, but could imperil the majority of the citizens in the United States and among our trading partners. This is incredibly shortsighted. If our trading partners suffer from financial instability they will be less likely be a source of revenue for U.S. exporters and U.S. investors in those countries—directly impacting Main Streets across America.

And again, financial instability among TPP nations, if not properly regulated, could quickly find its way back to the U.S. It is an injustice that the U.S. will not grant our TPP parties the right to regulate their financial systems, and is thus an injustice to the rights and livelihoods of the American people, as well.