Exchange Traded Funds an introduction

Post on: 6 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Christine Senior gives a beginner’s guide to Exchange Traded Funds

Exchange traded funds, or ETFs, may be something of a mystery to many trustees. Because they are relatively new and combine elements of several types of asset, ETFs can be difficult to understand at first.

An ETF is essentially a fund that holds a pool of shares of various companies, most usually replicating the components of a stock market index such as the FTSE100. It is itself traded on a stock exchange and can be bought and sold like a share.

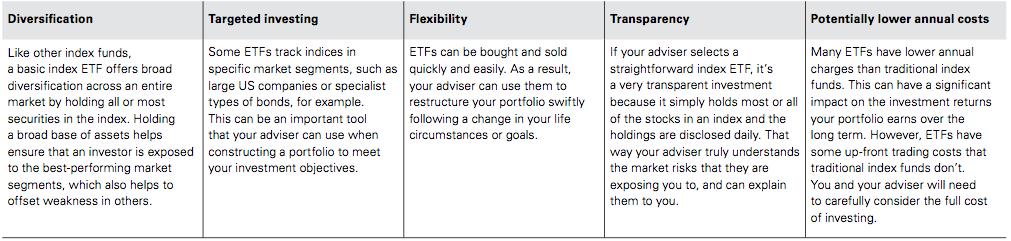

ETFs have many properties that make them attractive to pension schemes. They are liquid, meaning they can be bought and sold easily, and transparent, meaning it is easy to find out what shares they hold and what the ETF is worth at any given time. And as they cover a whole range of asset classes, from equities and bonds to currencies and commodities, they are useful to get access to the market return – or beta – of a whole index.

INSIDE ETFs: For passive investors (see: Passive Investing), ETFs compete directly with index tracker funds, which follow or track the make-up of a stock index. But unlike tracker funds, which can only be sold at certain times, ETFs can be traded in real-time, making them useful tools in other areas of portfolio management.

Exchange traded funds are open-ended in structure. This means that where there is strong demand for the product, the manager can create new a supply of ETFs to sell by exchanging a basket of shares representing the underlying index to create new ETF shares. Conversely ETF shares can be redeemed by converting them back to the underlying share of the index. It’s this mechanism which ensures the price of the ETF closely tracks the index it represents.

At the end of October 2010, over 130 providers globally had issued 2,409 ETFs which had assets totalling US$1,239bn (£785bn), according to research from BlackRock

The vast majority – around 70% – of ETFs are based on equities, or shares, although the true range of products is vast. The more popular indices like the S&P 500, which tracks the top 500 US companies, and the FTSE 100, are offered by more than one ETF provider. But more exotic, broader market indices covering the whole of emerging markets, or individual countries, or specific sectors like healthcare or utilities are also available and the range of products is continually growing.

There are even ETFs which use leverage, or borrowing, to increase returns and so-called ‘inverse’ ETFs which behave opposite to market movements. This is much like short-selling a stock (see Jargon Buster).

Recently there has been more interest in ETFs that invest in fixed income indices as investors seek the relative safety of bonds. Philip Philippides, head of UK and Ireland institutional sales for iShares at BlackRock says: “A fixed income ETF makes something which is very hard to trade – because it’s over the counter – extremely simple because it’s you can get a price at any time. It can trade as easily as an equity.”

PHYSICAL OR SYNTHETIC: ETFs come in two formats. Physical ETFs, which invest in actual shares. These are issued by asset managers. Synthetic ETFs which hold shares as well as using derivatives such as swaps (see Jargon Buster) to cover parts of the market which are more difficult to access through actual physical shares. This might be, for example, less liquid shares in emerging markets. Investment banks issue most synthetic ETFs.

Christos Costandinides, ETF strategist at Deutsche Bank, explains: “If an ETF provider is an asset manager with a strong capability in indexing then they may well choose physical replication. If the provider is an investment bank with a swap desk, which means they can source swaps cost effectively, then it generally makes more sense for them to get the replication that way.”

ETFS IN A PORTFOLIO: There are various ways ETFs can be used in a portfolio. As ETFs are so easy to trade in and out of, managers can use them for short-term tactical allocations. A scheme manager or discretionary asset manager – a manager with free rein to invest as they see fit – might use them to take advantage of an opportunity in a particular market or sector. If a manager was strongly in favour of a short-term position on US healthcare they could, for example, buy an ETF to access this sector.

Another possible use is for cash equitisation (see Jargon Buster). Cash flows received into the fund can be invested via an ETF as a short-term measure, while the fund reviews its strategy.

They are also a useful tool in managing a transition from one portfolio to another. If a European equities manager is being replaced, the transition manager can maintain exposure to the market by buying ETFs that track a European equity index.

WHAT DOES AN ETF COST? To get passive coverage of a particular market, ETFs face stiff competition from index tracker funds, which are usually more competitive in price. Pension funds have the size and scale to negotiate reductions in fees charged by fund providers, so for long term passive investments, index funds may have the edge.

ETF fees can be capped: for example State Street Global Advisors has capped the fee, or total expense ratio (TER, see Jargon Buster), of its MSCI S&P500 SPDR ETF at 30 basis points, meaning the most a scheme would pay is 0.3% of the value of its investment. Although headline fees in mutual funds can be as low as 10 basis points, or 0.1%, extra costs in the form of custody fees, audit fees and accounting fees may be added, giving a TER well above the basic management fee.

There are also opportunities to offset these higher costs to some degree through securities lending. For example, hedge fund managers who want to short-sell an equity need to borrow shares to sell. The securities lending market matches up stock borrowers with willing lenders who can earn extra return on their holdings.

“Depending on lending rates, those rates could compensate for the TER and in some cases could be higher than the TER.” says Vin Bhattacharjee, head of EMEA intermediary business at ETF provider State Street Global Advisors.

Trustees and pension schemes have been reluctant to invest in ETFs so far, but this may change. While ETFs may be a less attractive long term investment when compared to traditional passive funds, for schemes looking to make better use of cash, or in transition between different mangers, investing in ETFs can make sense.

JARGON BUSTER

TER Total Expense Ratio, or the total cost of an investment product. It may be a single fee, as for an ETF. For other types of fund this could include a separate management fee, custody fee, audit fee and so on.

Short-selling, or shorting A practice whereby hedge funds and other asset managers sell a stock they have borrowed from a third party such as a pension fund, but do not own, which they believe will drop in price. The hedge fund can then buy the stock back later more cheaply and make a profit on the difference in prices.

Swap A derivative which allows the holder to receive the return on an equity, or equity index, without holding it, through an agreement with a counterparty, usually an investment bank.

Cash equitisation Turning cash flows into equities, which can be achieved through buying an equity ETF. It can make sense for schemes to put unallocated cash into an ETF as a short term investment.

ETC Exchange Traded Commodities are similar to ETFs, but track the performance of an underlying commodity or commodities index. They too are traded on a stock exchange.

ETN Exchange Traded Notes are a type of fixed income security, also trading on a stock exchange, whose performance is linked to an underlying index.

PASSIVE INVESTING Passive investments are, as the name suggests, investments which take a ‘back seat’ approach. A passive or “tracker” fund will copy the composition of the index it is based on and stick to this as closely as possible. If Company X makes up 5% of the index and Company Y makes up 7% of the index, the two firms will represent 5% and 7% of the passive fund.

Passive investments provide ‘beta’ return, or the return of the whole market. Unlike active investments, which aim to outperform the market (or generate ‘alpha’), though managed skill, passive investments deliver returns in line with market movements. If the market rises by 10%, the value of the passive investment product should also rise by 10%. Equally, if the market falls, the value of the passive product will also fall by the same amount.