Economics Essays Should we worry about national debt

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Should we worry about national debt?

Governments have been borrowing for centuries. The figures for national debt are staggering. In the US, National debt is over $11 trillion. In the UK, debt is over 1.1 trillion. From a personal perspective, we are brought up to believe debt is a bad thing, and therefore it often feels worrying that national debt can be so large. But, how much should we worry about these levels of national debt?

One argument says that an increase in the national debt doesn’t cause any problems. What happens is that by borrowing we merely enable the present taxpayer to enjoy a higher disposable income now rather than in the future. A cut in the national debt, would mean higher taxes now, rather than later. Therefore, national debt is just a way to spread national output amongst different generations. To understand national debt, it is important to remember how it is financed. Government debt is essentially a transfer from one part of the population to another. (Who owns national debt? )

Historical national debt

Furthermore, National Debt has been much higher in the past. During the Second World War, the national debt of the UK and US, reached very high figures of over 150% of GDP. In the UK debt in the late 1940s reached over 200% of GDP. This is an example, of how a country can borrow during times of a national crisis and pay back the debt over a period of time. Therefore, national debt can be an effective way to deal with economic shocks such as recessions, financial crisis and world wars.

It is worth bearing in mind that in the 1940s, as well as paying for post war reconstruction the UK set up the NHS and welfare state. — There was no austerity panic in the 1940s! The high government debt levels of the 1940s and 1950s were not a barrier to the post war boom years of the 1950s and 1960s which saw record levels of economic growth.

Therefore government debt is not necessarily a barrier to economic growth and prosperity. But, it is also important to point out that there is no guarantee that borrowing 150% of GDP will always lead to two decades of economic prosperity. The UK nearly went bankrupt in the late 1940s, and was saved by a loan from the US. see: Why could UK borrow so much in the 1940s, and could we do the same again?

Growth and Debt

Another factor is that economic growth usually makes it easier to pay back national debt. If GDP increases faster than national debt, then we need a smaller % of incomes to pay the debt interest payments. If GDP growth averages 2.5% a year, then increasing national debt by 2.5% means we will spend the same percentage of income on debt payments (assuming constant interest rates)

- An analogy. When I took out a mortgage loan of 140,000, I was left with mortgage payments of 800 a month. In 2004, this was nearly 40% of my income. However, if my income increases by 3% a year. In 20 years time, it will be much easier to pay that mortgage payment of 800, it will hopefully be 15% of my income. To buy a house, it makes sense to borrow a mortgage and pay back over 30-40 years.

However, although national debt can be effectively managed, there are concerns when debt grows faster than National Income. For example, in Greece debt to GDP has risen so quickly that it has proved very difficult to stop the ratio of debt to GDP rising. (partly because spending cuts to reduce the deficit, caused lower GDP)

The fear for Eurozone economies, such as Italy, Portugal and Greece is not the levels of government borrowing, but the very poor prospects for economic growth. If the economy is stagnant, debt to GDP will continue to rise. If the economies were growing strongly, it would be much easier to reduce the debt to GDP ratio. (See also: Eurozone crisis )

Does higher borrowing cause higher bond yields?

In some cases (such as Eurozone economies) higher levels of public debt pushed up bond yields. Higher bond yields are damaging to the economy. It increases the cost of debt interest payments and is a reflection investors are nervous about the liquidity of government debt. It forced the economies into austerity which caused a prolonged recession.

However these countries with rising bond yields were in the Euro and did not have a Central Bank to buy bonds and ensure liqudity. In fact in 2012, the ECB took effective action to bring down bond yields (through unlimited purchases)

Countries with their own currency and Central Bank (e.g. UK and US) have the ability to purchase bonds and ensure liquidity. In the UK, the sharp rise in government debt between 2007 and 2012, led to a fall in bond yields. This shows that higher borrowing doesn’t have to translate into higher bond yields.

UK Bond yields and UK borrowing

Rise in net borrowing (annual budget deficit) didn’t cause bond yields to rise.

Why is there greater demand for government debt in a recession?

The UK has seen a fall in bond yields during the recession of 2008-12. This is because, in a recession, private sector saving rises. Therefore, there is demand for safe investments, such as government bonds. In a recession, people don’t want to take risks, therefore demand for shares and private investment tends to fall. In a recession, government borrowing doesn’t tend to cause crowding out. Government borrowing is merely mopping up private sector saving.

From a Keynesian perspective, government borrowing can help to boost aggregate demand and offset the fall in Aggregate Demand. In a recession, borrowing can provide a boost to economic growth and therefore, help improve tax revenues.

Possible reasons to be concerned about government borrowing

1. Structural deficit. If government borrowing reflects a fundamental disequilibirum between spending and tax revenue then this may lead to unsustainable debt levels in the future.

2. If borrowing is to finance welfare payments with an increased level of dependency. Paying pensions and health care to an ageing population, will do nothing to facilitate economic growth and improve tax revenues, and it will become more difficult to finance the national debt. Some are concerned that countries like Japan have a high debt (over 220% of GDP), but also a rapidly ageing population which will put even more pressure on Japanese debt levels.

- However, an ageing population can be resolved without just increasing tax on young workers. The retirement age can be increase to keep the same% of population in workforce.

3. Inflationary Pressure. There is a concern that higher levels of national debt can cause inflation. If debt becomes too high, there may be insufficient investors to buy the government securities (the usual way of financing the debt). Therefore, the government may be tempted (or forced) to fill the shortfall in revenue by printing money. Printing money and increasing the money supply, will lead to inflation. The problem with inflation, is that it devalues the value of bonds, people will sell bonds, leading to higher interest rates on bonds and higher debt interest payments. If investors see inflation is getting out of control, people will not want to hold bonds. Foreign investors will sell their securities and this will cause a devaluation in the currency. This is particularly a problem for the US, where foreign countries hold a high % of the national debt.The hyperinflation of Germany in 1922-23 was caused by the government printing money to finance reparation payments to the allies.

- However, it should be pointed out, this hyperinflation is quite rare and only occurs if the government prints money recklessly without regard to the fundamental economic situation. Quantitative easing in 2009-12 didn’t cause inflation in the UK and US. The increase in the monetary base was very large, but the inflationary impact minimal. — Inflation and quantitative easing .

4. Crowding Out. It is argued that if government borrowing increases, it will cause crowding out of the private sector. If the private sector buy bonds it means the private sector has less funds for private sector investment. Also, if borrowing increases, interest rates may rise. Higher interest rates also reduce private sector spending and investment.

- However, in a recession, crowding out doesn’t occur because the private sector want to buy government bonds

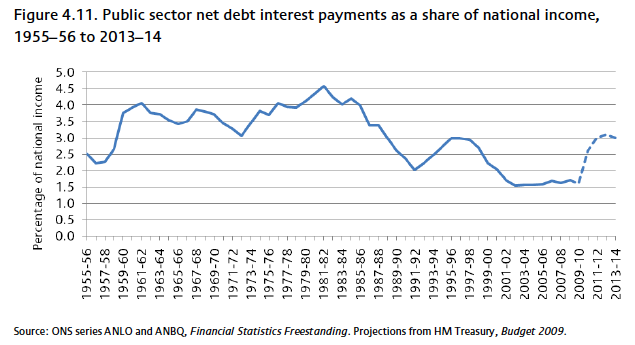

5. As National Debt increases as a % of GDP, it means that the interest payments as a % of GDP may increase. Therefore, higher levels of taxes have to be spent on just financing the national debt.

However, this doesn’t necessarily occur. The UK has seen fairly stable interest payments as a % of GDP, despite rising debt levels. In a recession, bond yields tend to fall, therefore it becomes cheaper to borrow. See debt interest payments

Conclusion — should we worry about government debt?

It depends when and why the government are borrowing. In a recession, with a fall in private sector demand, a rise in government borrowing is beneficial for maintaining aggregate demand in the economy. If private sector spending fell and we also tried to reduce government borrowing, we could see a precipitous fall in aggregate demand, and a deep recession. See: Austerity can be self-defeating .

If the government is borrowing to finance public sector investment, then this can lead to improved economic growth and better tax revenues in the future.

When should we worry about government debt?

- If the government increases debt during a period of economic growth — the higher borrowing is likely to crowd out the private sector and lead to a decline in private sector investment.

- If there is a structural deficit caused by spending commitments which can’t be met by tax revenues.

- If the government responds to higher debt by printing money; this can cause inflation. e.g. case of Zimbabwe, Germany 1920s. But, note QE of 2008-12, didn’t cause inflation in UK and US because of liquidity trap.