Don’t worry about a stock market drop

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Don’t worry about a stock market drop

A feeling of vertigo may seem natural as Wall Street approaches a record and stock markets around the world climb to their highest levels since 2007. With the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index now only 0.5 percent away from its 2007 high of 1565 and with the Dow Jones industrial average scaling new peaks almost daily, what will investors expect to see when they reach the mountaintop? The mountaineering analogy suggests, at best, a long descent and, at worst, a precipitous drop. But how literally should we take such metaphors?

Bearish analysts often claim that stock market peaks have always been followed by sharp falls, citing as evidence the record high of October 2007, which was quickly followed by a 57 percent collapse in 2008-09. They add that the previous peak, in March 2000, was followed by a 37 percent plunge and that last major high before that, in August 1987, preceded the biggest-ever market crash, in October 1987. These precedents, along with the even more vertiginous peaks of 1989 in Japan and 1929 on Wall Street, certainly sound scary, but they are meaningless.

It may be true that all major market peaks have been followed by big declines, but the reason is semantics, not finance or economics. A peak is, by definition, a high point followed by a decline. A new market high that is not followed by a fall in prices is simply not called a peak. A record of this kind, far from preceding a steep decline, tends to act as a staging post for higher prices. Looking back through history, it turns out that this benign type of record, paving the way for higher prices, is actually the norm.

There have been eight occasions in the past 100 years when stock prices on Wall Street, as gauged by the S&P 500 or its predecessor benchmarks, have broken through to significant new highs, defined for the purpose of this analysis as a breach of previous records by 3 percent or more: December 1924, September 1954, September 1963, August 1967, May 1972, July 1980, November 1982 and July 1989. All these record highs were followed by further price gains, and none experienced a significant decline for at least six months.

This history starts in 1924, when Wall Street broke out of a 10-year bear market that started before the World War One. After December 1924, when stock prices finally managed to break through their prewar peak, the stock market immediately advanced by a further 23 percent in the next 12 months. It then accelerated and soared much higher, gaining a total of 216 percent. It was only five years later, in September 1929, that stock prices hit a peak in the mountaineering sense, followed by the greatest bear market of all time.

It took the stock market 25 years to break the 1929 high, but when this finally happened that was emphatically a reason to celebrate rather than panic. After September 1954, when the 1929 high was finally breached, the S&P advanced by 36 percent in 12 months and by a total of 121 percent before the next major decline, which began seven years later in December 1961. With economic conditions in the early 1960s broadly favorable, this bear market was relatively brief and it took less than two years for stock prices to set a record in September 1963. Having set that new high, the S&P advanced by a further 16 percent in the next year and by 50 percent to a series of new peaks, in January 1966, August 1967 and December 1968.

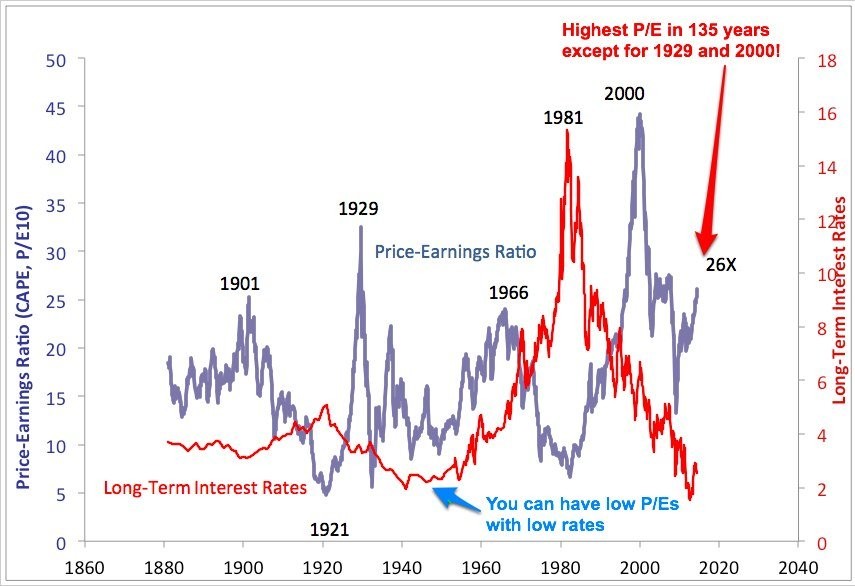

It was only at that point, in the late 1960s, that stock market performance really deteriorated, as the global economy faced an inflation crisis, the disintegration of the postwar currency system and the 1973 oil shock. As a result, the trough in stock prices that followed the peak of December 1968 lasted more than three years. When stock markets rebounded to a new record in May 1972, this was followed by only a 9 percent advance, peaking in January 1973, when global equities plunged into their deepest and most protracted bear market since the 1930s. The S&P took seven years to clamber back to its January 1973 peak – and although the high set in July 1980 paved the way for a few months of further gains, these were quickly followed by another terrible bear market, starting in December 1980, in response to the second oil shock and an unprecedented double-dip U.S. recession.

It was only in late 1982 that the investment world finally emerged from this long series of economic disasters. When Wall Street confirmed this recovery on Nov. 3, 1982, by breaking out to a new high, this record was definitely not a reason for anxiety but, again, for celebration. Indeed, from that day onward stock markets around the world advanced almost without interruption until August 1987, by which time the S&P had gained 138 percent from its November 1982 high. And even bigger gains were to follow. Although the bull market was abruptly interrupted by the stock market crash of 1987, another record was set in July 1989, and this paved the way for the biggest winning streak of all time – a total gain of 360 percent from the July 1989 record to the final bull market peak of 1527 for the S&P on March 24, 2000.

Thirteen years later the S&P 500 has still not exceeded that 2000 high by a decisive margin. For such a breakout to occur, it would have to break not only the 2000 high but also the marginally higher record of 2007, by a few percentage points. That may not happen, and if Wall Street fails to overcome its 2007 record, a substantial setback is likely for all global stock markets. If, on the other hand, the S&P 500 does set a significant record, the message of history will be clear: New highs on Wall Street are much more likely to be springboards for further advances than peaks from which prices plunge.

PHOTO: Traders work on the floor at the New York Stock Exchange, March 14, 2013. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid