Determining the Optimal Rebalancing Frequency

Post on: 27 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Within the investment consulting community, it has long been preached that periodically rebalancing a multi-asset class portfolio is a requirement for an effective investment policy. However, little research is available to help in determining what is the optimal rebalancing frequency. From an efficiency and simplicity standpoint, rebalancing at a set time period, such as annually, may be easiest. However, if you consider the taxes and transaction costs that result from rebalancing, we question whether an investor is better off with such a simplified structure.

In this analysis we seek to interpret what we believe to be the optimal rebalancing frequency after considering taxes and transaction costs. In this analysis, we will discuss our rationale for believing that investors are better off establishing a disciplined rebalancing frequency. For those investors with taxable assets and an intermediate to long-term investment horizon, we find a rebalancing strategy that uses a 5 percent rebalance trigger (essentially rebalancing a portfolio whenever an allocation deviates 5 percent from its target weight) is the most optimal when considering return, risk and the costs associated with rebalancing.

Costs of Rebalancing

The visible, hard costs of rebalancing are transaction costs and realized taxable gains. Whether an investor pays transaction commissions or pays for services on a fee basis, transaction costs occur at some level. Additionally, all clients are affected by the bid/ask spread that must be paid when selling and purchasing securities in order to rebalance. While the bid/ ask spread is typically insignificant (often as low as $0.01 a share), this cost can add up when rebalancing an entire portfolio. For clients with taxable investments, after-tax returns are just as important, if not more important, than pre-tax returns. Therefore, controlling the unnecessary recognition of capital gains is important in maximizing after-tax returns. Due to the nature of rebalancing, those assets that have appreciated the most, relative to the others within the portfolio, are sold in favor of increasing the allocation to those assets that have not performed as well on an absolute basis. This naturally creates a tendency to sell gains, therefore increasing your tax liability.

Collectively, taxes and transaction costs must be considered when setting a rebalancing frequency. Taxes may not apply to all investors or all aspects of a portfolio. For example, investors with tax-deferred investments in annuities, IRAs or 401(k) plans will not have to consider tax costs when determining a rebalancing discipline. Transaction costs will always be a constant consideration when determining a rebalancing frequency.

Methods of Rebalancing

There are five basic forms of rebalancing used by individual and institutional investors:

- No rebalancing

- Rebalancing on demand

- Rebalance frequencies

- Allocation triggers

- Hybrid

With the first method, no rebalancing. an investor essentially is allowing their portfolio to drift and will allow the market to rebalance the portfolio for them. As large-company stocks appreciate and bonds decline, the allocation to bonds will fall and the allocation to large-company stocks will rise.

Rebalancing on demand does not establish a set rebalancing guideline; rather, it gives the investor the freedom to make tactical decisions on when they believe it is appropriate to rebalance their portfolio. For example, in 2003, the stock market regained its bullish position with large-company stocks rising 28.7 percent 1 and small-company stocks rising 47.3 percent 2. After a year such as that, a natural reaction may be have been to take some of these gains off of the table and reallocate them to bonds. However, with expectations of rising interest rates in 2004 and a negative outlook for bonds, an investor rebalancing on demand may have made the tactical decision to delay rebalancing to bonds until rates had risen.

Rebalancing frequencies is the most common and most disciplined rebalancing method. An investor chooses a rate of recurrence to rebalance, such as quarterly, semiannually or annually. Regardless of market direction or expectations for the market, a portfolio is rebalanced based on a predetermined frequency.

Allocation triggers set boundaries on an asset allocation, thereby forcing a portfolio to be rebalanced when a boundary is violated. For example, a 5 percent trigger set on a 50/50 stock and bond allocation would rebalance the portfolio whenever one asset class reached 55 percent or 45 percent. While less disciplined than a set rebalancing frequency, this method allows portfolios to shift with the market and does not rebalance unless there has been a significant move.

Finally, the hybrid method combines both a rebalance frequency with an allocation trigger. An example would be setting an annual rebalance frequency with a 5 percent trigger and stating that the portfolio will be rebalanced no less than annually. However if the portfolio deviates by 5 percent from its target during the year, the portfolio will be rebalanced at that time as well.

Collectively, these methods provide investors with latitude in determining to what extent they wish to let market movements rebalance their portfolios. In addition, investors also retain the freedom of determining the discipline they wish to instill within their investment policy based on their comfort with the markets. The lower the number of occurrences to rebalance the portfolio, the lower the transaction costs and taxable effects of rebalancing will be.

Optimal Rebalancing Frequency

At the individual level, investors should set a rebalancing frequency based on what is optimal to them in order to control risk and enhance return, while at the same time minimizing their costs (transaction costs and taxes).

Research on the subject of selecting an optimal rebalancing frequency is relatively scarce. In the research that has been conducted, an overwhelmingly consistent message throughout is the idea that it doesn’t matter what your method of rebalancing is, all that is important is that you rebalance.

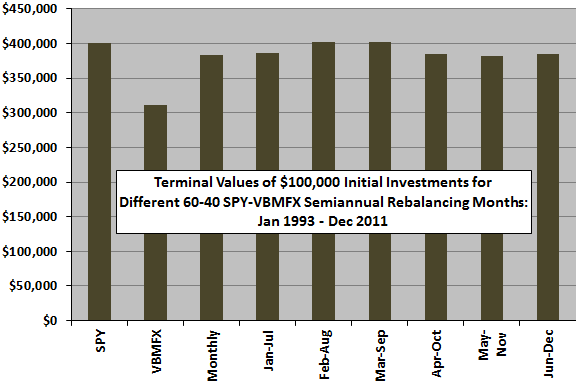

To test these findings, we conducted our own research on two different scenarios to determine the optimal rebalancing method and frequency. To construct our conclusions, we compared (back-tested) a number of rebalancing methods against historical investment returns. We began this comparison by first looking at a simple portfolio that was invested 60 percent in equities and 40 percent in bonds. The methods considered for this simple comparison included: not rebalancing, annual rebalancing, quarterly rebalancing and rebalancing based on a 5 percent trigger. In addition, we ran a second comparison of a more diversified allocation that included large cap, small cap and foreign stocks along with bonds. With this scenario we added two additional rebalancing methods: a 10 percent trigger and a hybrid 5 percent trigger with automatic annual rebalancing.

Analysis of a 60/40 stock and bond mix

In comparing the effects of rebalancing a 60 percent stock/40 percent bond allocation 3 from 1979 through 2003 (Figure 1), it was quite apparent that rebalancing alone reduced volatility by over 18 percent, dropping the long-term standard deviation down from 12.2 percent down to 10.3 percent. The difference in volatility (as measured by standard deviation) among the three rebalancing frequencies (annual, quarterly and a 5 percent trigger) was minimal, signaling that it is not the method of rebalancing that matters, but just the decision to rebalance that makes a difference. When comparing the returns of these methods, not rebalancing the portfolio provided a marginally better return than the various rebalancing methods.

Figure 1: Analysis Period January 1979-December 2003