Deleveraging A fate worse than debt

Post on: 28 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Add this article to your reading list by clicking this button

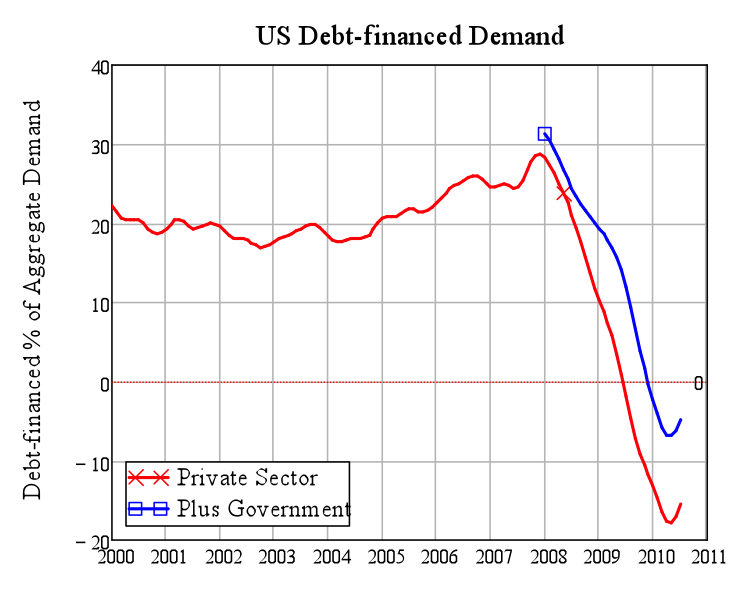

IT IS ugly, but deleveraging is the word of the moment. Financial institutions, desperate to repair the damage inflicted on their balance-sheets by mortgage-related securities, sell assets. In doing so, they exacerbate the problem. Forced sales push down the prices of assets, worsening the balance-sheets of other investors, forcing more asset sales, and so on. In the end, the government is the only entity left in the game with a balance-sheet strong enough to keep buying.

The Bush administrations bail-out plan, even if it gets through Congress, may not be the end of the finance industrys problems. The travails of investment banks will inevitably cause problems for hedge funds, which depend for their finances on institutions such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Many hedge funds have already cut positions since the credit crunch started in the summer of 2007, and banks have tightened the terms on which they will do business with them. This has been particularly true for those that sought funding through the prime-brokerage arms of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers before they were wiped out.

In this section

The volatility of financial markets may intensify the pain, since both brokers and hedge funds use models which lead them to sell assets when prices move down sharply. Some hedge funds may have to give up altogether. Around 15% more were liquidated in the first half of 2008 than in the first half of 2007, according to Hedge Fund Research, a consultancy.

What hurts finance affects the rest of the economy in spades. Tim Bond, of Barclays Capital, reckons that, thanks to the gearing effect, a shortfall of bank capital of around $170 billion may reduce the potential supply of credit by $1.7 trillion.

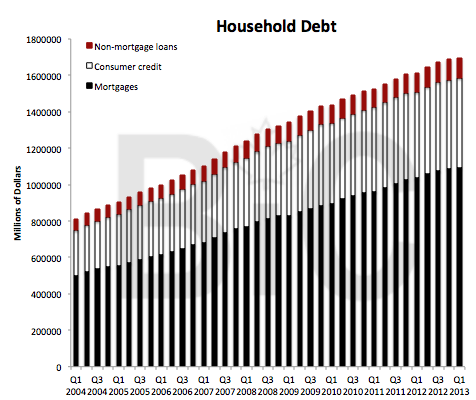

A cut in overall lending would be a complete reversal of trend. Morgan Stanley reckons that total American debt (ie, the gross debt of households, companies and the government) has risen inexorably since 1980 to more than 300% of GDP (see chart), higher than it was in the Depression. Consumers, in particular, were encouraged to borrow by low unemployment and interest rates and (until last year) rising asset prices. Their debt jumped from 71% of GDP in 2000 to 100% in 2007, a bigger increase in seven years than had occurred in the previous 20.

If consumers start to save more or borrow less, spending suffers. In the last three months, America has seen the weakest car sales since 1993, according to Bloomberg. A general decline in demand will cause businesses to shed jobs, creating further falls in demand and more bad debts.

Once started, the process is hard to stop. “What the financial and household sectors are doing is unwinding more than ten years of a credit boom,” says George Magnus, an economist at UBS. “The idea that they can rid themselves of this problem in a matter of months is pie in the sky.”

Then there are businesses. Thanks to strong recent profits, many firms are less geared than they were earlier this decade during the telecoms bust. Nevertheless, there are plenty of big borrowers around, including carmakers and businesses bought by private-equity groups. They may struggle to refinance their debts as they fall due. Martin Fridson, of Fridson Investment Advisors, says that the default rate on high-yield bonds may climb to 10%.

Even firms that are not heavily in debt may think twice about expanding. According to Morgan Stanley, changes in bankers attitudes to lending tend to lead business investment by three quarters. If the past pattern holds good, by the summer of next year investment may be falling at an annual rate of more than 10%. That will further depress economic growth.

The danger is of a “second-round effect”, as the crisis in finance affects the economy, leading to further problems in finance. Mortgages may be the problem asset of the moment but next year the worry may be about credit cards, car loans and corporate debt.

The Bush administrations rescue plan aims to arrest this deleveraging cycle. But it will not be easy. “Eventually they will put the fire out,” says Nick Carn, a partner at Odey Asset Management, a hedge fund. “The question is how much gets burned between now and then.”