Current Account Deficits Is There a Problem Back to Basics Finance Development

Post on: 27 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem?

Finance & Development

There can be consequences when the amount a country spends abroad is wildly different from what it receives from the outside world

One big yard sale (photo: John Van Hasselt/Sygma/Corbis)

The current account balance seems to be an abstruse economic concept. But in countries that are spending a lot more abroad than they are taking in, the current account is the point at which international economics collides with political reality. When countries run large deficits, businesses, trade unions, and parliamentarians are often quick to point accusing fingers at trading partners and make charges about unfair practices. Tension between the United States and China about which country is primarily responsible for the trade imbalance between the two has thrown the spotlight on the broader consequences for the international financial system when some countries run large and persistent current account deficits and others accumulate big surpluses.

Measuring the current account

There are several points at issueincluding what a current account deficit or surplus really means and the many ways that a current account balance is measured.

The current account can be expressed as the difference between the value of exports of goods and services and the value of imports of goods and services. A deficit then means that the country is importing more goods and services than it is exportingalthough the current account also includes net income (such as interest and dividends) and transfers from abroad (such as foreign aid), which are usually a small fraction of the total. Expressed this way, a current account deficit often raises the hackles of protectionists, whoapparently forgetting that a main reason to export is to be able to importthink that exports are good and imports are bad.

The current account can also be expressed as the difference between national (both public and private) savings and investment. A current account deficit may therefore reflect a low level of national savings relative to investment or a high rate of investmentor both. For capital-poor developing countries, which have more investment opportunities than they can afford to undertake because of low levels of domestic savings, a current account deficit may be natural. A deficit potentially spurs faster output growth and economic developmentalthough recent research does not indicate that developing countries that run current account deficits grow faster (perhaps because their less developed domestic financial systems cannot allocate foreign capital efficiently). Moreover, in practice, private capital often flows from developing to advanced economies. The advanced economies, such as the United States (see chart), run current account deficits, whereas developing countries and emerging market economies often run surpluses or near surpluses. Very poor countries typically run large current account deficits, in proportion to their gross domestic product (GDP), that are financed by official grants and loans.

One point that the savings-investment balance approach underscores is that protectionist policies are unlikely to be of much use in improving the current account balance because there is no obvious connection between protectionism and savings or investment.

Another way to look at the current account is in terms of the timing of trade. We are used to intratemporal tradeexchanging cloth for wine today. But we can also think of intertemporal tradeimporting goods today (running a current account deficit) and, in return, exporting goods in the future (running a current account surplus then). Just as a country may import one good and export another under intratemporal trade, there is no reason why a country should not import goods of today and export goods of tomorrow.

Intertemporal theories of the current account also stress the consumption-smoothing role that current account deficits and surpluses can play. For instance, if a country is struck by a shockperhaps a natural disasterthat temporarily depresses its ability to access productive capacity, rather than take the full brunt of the shock immediately, the country can spread out the pain over time by running a current account deficit. Conversely, research also suggests that countries that are subject to large shocks should, on average, run current account surpluses as a form of precautionary saving.

When persistent is too persistent

Does it matter how long a country runs a current account deficit? When a country runs a current account deficit, it is building up liabilities to the rest of the world that are financed by flows in the financial account. Eventually, these need to be paid back. Common sense suggests that if a country fritters away its borrowed foreign funds on spending that yields no long-term productive gains, then its ability to repayits basic solvencymight come into question. This is because solvency requires that the country be willing and able to generate (eventually) sufficient current account surpluses to repay what it has borrowed to finance the current account deficits. Therefore, whether a country should run a current account deficit (borrow more) depends on the extent of its foreign liabilities (its external debt) and on whether the borrowing will finance investment with a higher marginal product than the interest rate (or rate of return) the country has to pay on its foreign liabilities.

But even if the country is intertemporally solventmeaning that current liabilities will be covered by future revenuesits current account deficit may become unsustainable if it is unable to secure the necessary financing. While some countries (such as Australia and New Zealand) have been able to maintain current account deficits averaging about 4 1/2 to 5 percent of GDP for several decades, others (such as Mexico in 1995, Thailand in 1997, and several economies during the recent global crisis) experienced sharp reversals of their current account deficits after private financing withdrew during the financial crisis.

Such reversals can be highly disruptive because private consumption, investment, and government expenditure must be curtailed abruptly when foreign financing is no longer available and, indeed, a country is forced to run large surpluses to repay in short order what it borrowed in the past. This suggests thatregardless of why a country has a current account deficit (and even if the deficit reflects desirable underlying trends)large and persistent deficits call for caution, lest a country experience an abrupt and painful reversal of financing.

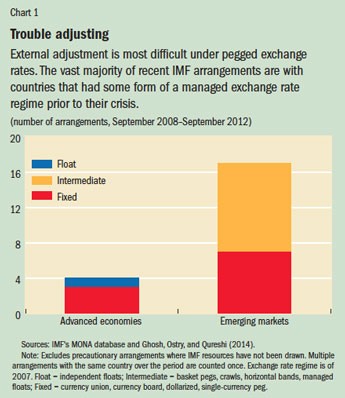

What determines whether a country experiences such a reversal? Empirical research suggests that an overvalued real exchange rate. inadequate foreign exchange reserves, excessively fast domestic credit growth, unfavorable terms of trade shocks, low growth in partner countries, and higher interest rates in industrial countries influence the occurrence of reversals. More recent literature has also focused on the importance of balance sheet vulnerabilities in the run-up to a crisissuch as the extent to which companies have large liabilities in foreign currencies such as dollars or maturity mismatches that occur when companies have more short-term liabilities than short-term assets and more medium- and long-term assets relative to their liabilities. Recent research has also underscored the importance of the composition of capital inflowsfor example, the relative stability of foreign direct investment compared with more volatile short-term investment flows, such as in equities and bonds. Moreover, weak financial sectors can often increase a countrys vulnerability to a reversal of investment flows as banks borrow money from abroad and make risky domestic loans. Conversely, a more flexible policy frameworksuch as a flexible exchange rate regime, a higher degree of openness, export diversification, and coherent fiscal and monetary policiescombined with financial sector development could help a country with persistent deficits be less vulnerable to a reversal by allowing greater room for better shock absorption.

Judging whether deficits are bad

A common complaint about economics is that the answer to any question is, It all depends. It is true that economic theory tells us that whether a deficit is good or bad depends on the factors giving rise to that deficit, but economic theory also tells us what to look for in assessing the desirability of a deficit.

If the deficit reflects an excess of imports over exports, it may be indicative of competitiveness problems, but because the current account deficit also implies an excess of investment over savings, it could equally be pointing to a highly productive, growing economy. If the deficit reflects low savings rather than high investment, it could be caused by reckless fiscal policy or a consumption binge. Or it could reflect perfectly sensible intertemporal trade, perhaps because of a temporary shock or shifting demographics. Without knowing which of these is at play, it makes little sense to talk of a deficit being good or bad. Deficits reflect underlying economic trends, which may be desirable or undesirable for a country at a particular point in time.

Atish Ghosh is an Assistant Director in the IMFs Research Department and Uma Ramakrishnan is a Deputy Division Chief in the IMFs Strategy, Policy, and Review Department.