Currency markets Yen and yang

Post on: 22 Август, 2015 No Comment

WHICH country has the world’s most undervalued currency? Most people would answer China. Yet by many measures the Japanese yen is now cheaper than the Chinese yuan. It cannot be long before America and Europe put Japan in the dock, alongside China, and accuse it of keeping its currency unfairly low.

Until this year the yen’s weakness was easy to explain: since 2001 the Bank of Japan ( B o J ) had been printing loads of money in order to defeat deflation. An increased supply of yen relative to that of other currencies pushed down its price. But the yen’s softness this year is a puzzle. Since the B o J abandoned “quantitative easing” in March, Japan’s monetary base has withered. Deflation has gone away, and in July the B o J raised interest rates, which had been stuck at zero for five years. Furthermore, Japan had a whopping current-account surplus of $165 billion in the year to July (the latest figure for China, for 2005, is only $161 billion, although it is expected to rise in 2006). In many respects, the yen should be climbing.

Instead, since March it has fallen slightly against the dollar and by as much as 8% against the euro, which fetched a record ¥150 earlier in September, before edging back up a bit. Since mid-2001 the yen has fallen by around 35% against the euro, while against the weaker dollar it is little changed. Japanese exporters have also gained competitiveness relative to South Korea, where the won has risen strongly against the dollar during the past year.

In this section

Related items

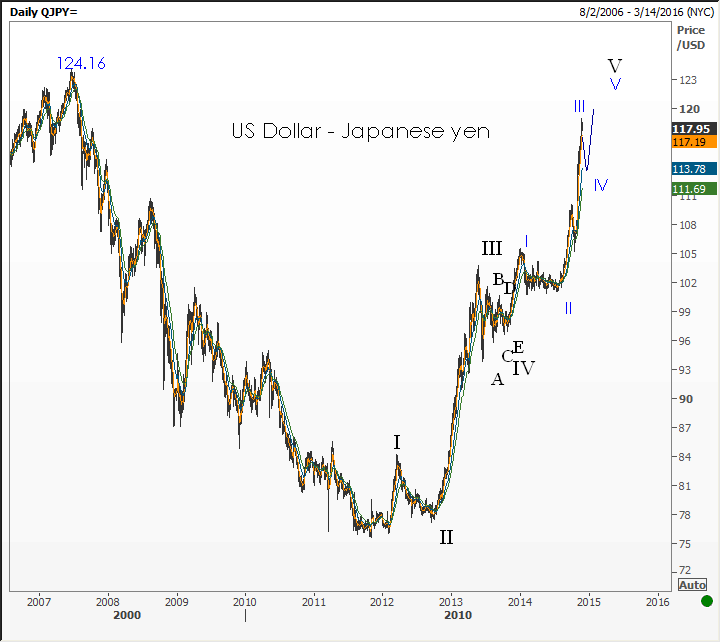

Not only is the yen cheap in nominal terms, but many years of falling prices in Japan have made it even more competitive. Its real trade-weighted value fell this month to its lowest since 1982 (see chart). The latest update of The Economist ‘s Big Mac index (see article ) showed that the yen was by far the most undervalued of the developed world’s currencies—ie, hamburgers are cheapest in Tokyo. Using a more sophisticated model, Stephen Jen, of Morgan Stanley, reckons that the yen is 12% undervalued against the dollar, whereas the yuan is only 7% too weak. Against the euro, the yen is almost 30% below its fair value.

If the yen is the most mispriced currency on the planet, why are Japan’s trade partners not complaining loudly, as they do about the yuan? Some European finance ministers and central bankers, including Jean-Claude Trichet, the president of the European Central Bank, have started to argue recently that the yen is not bearing its fair share of the dollar’s decline. But a big difference between Japan and China is that the yen floats freely and is not being held down by currency intervention as it was back in 2003-04.

Such a cheap currency might seem a good investment. But to predict where the yen is heading, you have to understand why it is so weak today. One reason is that at 0.25%, Japanese interest rates are still unattractive. And inflation has gone up by more than the quarter-point rise in Japanese interest rates, leaving real rates close to zero and even lower than last year.

The most popular explanation of the yen’s languor is a revival of the “carry trade” (ie, borrowing in cheap yen to buy higher-yielding investments elsewhere). This means selling the currency and thus pushes it down. In the past month or so, carry trades have become more attractive; the expectation that the B o J would raise interest rates again this year has faded as a result of slower economic data. If this is the case, at some stage the yen could rebound sharply if America’s economy stumbles and falling American interest rates narrow the gap with Japan’s.

However, Mr Jen is sceptical that the carry trade is the main culprit. He reckons that most investments have gone into dollars not euros, and so cannot explain why the yen has gained against the European currency. Moreover, net outflows from Japan of investment in fixed-income bonds have actually declined this year—especially in the past few months.

Mr Jen has an alternative explanation for why the yen is so feeble against the euro: the “global funnelling hypothesis”. This focuses on the net trade and capital flows of Asian and oil-exporting countries, which could run a combined current-account surplus of around $900 billion this year. In simple terms, the world buys from these countries and they then invest the net proceeds in financial markets.

Most international trade is settled in dollars or euros, so importers have to sell their local currencies in order to buy from abroad. Mr Jen calls these “upstream currency flows”. “Downstream flows”, in contrast, are what Asia and oil exporters do with their accumulated reserves. The currency compositions of the two flows do not necessarily match.

Because Asian countries trade a lot with each other, the bulk of upstream flows involves the selling of yen and other Asian currencies. In contrast, most downstream flows go into dollars and euros. Central banks prefer to put money into well-developed financial markets, so the liquid and secure markets of America, the euro area and Britain attract more capital.

This causes a funnelling from Asian currencies into dollars and euros. Emerging economies’ rising foreign reserves therefore push the yen down against the euro, regardless of fair-value calculations. This also explains the strength of the pound. Recent figures show that it has knocked the yen off its perch as the world’s third most popular reserve currency.

If correct, this theory suggests that the yen could remain weak for longer than many analysts expect. In the long term, however, the yen’s huge undervaluation means that it will eventually bounce back. Last week was the 21st birthday of the G7 ‘s Plaza Accord, which triggered a huge rise in the yen. The yen is much more undervalued today than it was then.