CreditDefault Swaps Weapons of Mass Speculation

Post on: 8 Май, 2015 No Comment

Error.

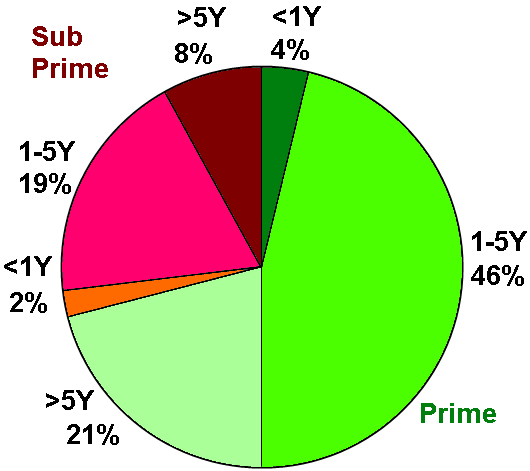

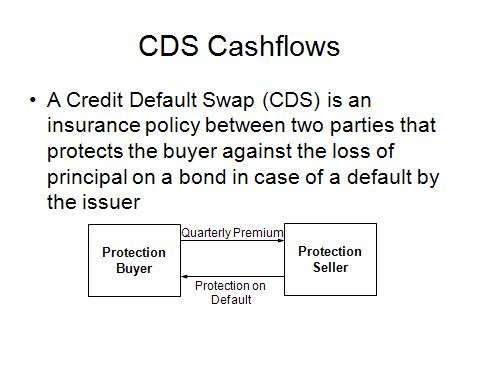

DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT derivatives called credit-default swaps, or CDS? There’s no reason one should. Even today, CDS, which represent bets on the default risk of various debt issues, remain an obscure corner of the global-finance market, inhabited mostly by big banks and brokerages, hedge funds and other institutions. Denizens of the CDS market strike customized insurance deals covering all manner of debt, from corporate, sovereign and municipal bonds to asset-backed securitization paper. There’s no formal clearing house for this over-the-counter market. Nor is there much public reporting of the pricing of the trades.

Buying credit-default swap protection is the ultimate bearish bet. Scott Pollack

But don’t be fooled by the low profile of the business. In the decade since credit- default swaps were invented, the market has exploded in size, to some $62 trillion of CDS deals outstanding from just $1 trillion in 2000, according to industry estimates. This dwarfs the size of the underlying bond issues.

Beyond concerns about its size, the CDS market seems to have become a weapon of mass speculation that is destabilizing international debt and even equity markets. That looks to be true in the subprime-debt-induced crisis of recent months that still has the credit markets in a deep-freeze. At the height of the crisis, in the first quarter, the price of credit-default insurance for key financial companies zoomed to once-unimaginable heights, signaling rightly or wrongly the imminent default of their debt issues.

The run-up was induced partly by panic among debt holders and others seeking to hedge their financial exposure at any price. But other factors, some suggesting a deliberate attempt by bearish investors to sow doubt about a company’s financial condition and thus push up CDS prices, may have played a role. In the CDS market, a well-placed rumor of trouble, or snippet of negative analysis, can have an outsized impact on positions, because much like a put, the investor risks only the premium to control the action on a potentially large position. Buying CDS protection is the ultimate bear bet, and the incentive of CDS holders to accentuate the negative, particularly to the financial press, is almost irresistible.

There are intimations, at least, that such activity occurred. The Securities and Exchange Commission reportedly has launched an investigation of the role rumor-mongering might have played in fomenting the fatal liquidity crisis at Bear Stearns (ticker: BSC). Similarly, Lehman Brothers (LEH) was afflicted by a spate of rumors in the weeks before and after the bail-out of Bear in March, reportedly prompting another SEC probe.

One has only to look at the charts of one-year and five-year credit-default prices for both Bear and Lehman, collected by the price-reporting service Credit Market Analysis, to see the fast, sharp rise, and fairly sudden decline, in the companies’ CDS quotes. For Bear Stearns, at least, the spike in the price-protection costs triggered a fatal feedback loop.

CREDIT-DEFAULT SWAPS WERE developed in the mid-1990s to offer investors a pure play on ever-changing credit spreads, or the yield gaps that exist between various debt instruments and ultra-safe Treasuries. Thus prices, or premium rates, are quoted in basis points, or one-hundredths of a percentage point of the par value of the bonds being insured. The buyers of CDS typically are hedgers seeking to protect against the risk of untoward widening in the credit spreads on their holdings, or speculators with no underlying debt positions, looking to profit from the same. In the event of a default, buyers receive the full difference between the par value and recovery value of the CDS-insured bonds.

Among hedge funds, two big winners last year were Passport II Global and Balestra Capital, Nos. 1 and 2 in Barron’s annual survey of the top 75 hedge funds (Scaling the Heights , April 14), with annual returns of 219% and 199%, respectively. Propitious CDS purchases also contributed greatly to the $12 billion in returns that John Paulson of Paulson & Co. rang up last year, the biggest annual haul any hedge fund has made.

All three fund managers caught the once-in-a-lifetime expansion of credit spreads in the past year or two, from negligible levels of, say, 30 basis points, or 0.3% of the bonds being insured, out to 1,000 basis points, or 10% of the bonds being insured. The profit on this position, when it was closed out a year later, wasn’t just a 10-bagger of the sort former mutual-fund legend Peter Lynch used to brag about. It was nearly a 100-to-1 return, after figuring in the present value of the carrying costs of 1.5% (five annual payments of 0.3%) and the payoff of 4,000 basis points (representing the 1,000 basis-point premium multiplied by the four years left on the contract).

A CLOSER LOOK AT OUR CHARTS indicates how emotional the CDS market became in recent months. CDS of Countrywide and Bear both rose to nosebleed levels in the first quarter, then plummeted after each company found a merger partner with a stronger credit profile. In other words, both Countrywide and Bear, as evidenced by their takeovers, had implicit equity value, even though, for Countrywide, the one-year CDS premium rate soared to 4,261 basis points, implying the likelihood of an imminent bankruptcy with a paltry recovery.

The CDS of finance company CIT and Lehman traced similar trajectories on short-lived rumors to the effect the balance sheets of both companies were too illiquid to ensure survival. Yet, look how quickly the fever passed after soothing words from the managements of each and the companies’ successful ability to raise capital.

The CDS charts of bond insurers Ambac and MBIA show a different pattern. There’s the initial earthquake in January, followed by severe aftershocks in February, during congressional hearings on the monolines’ capital adequacy, and in March, when Bear Stearns melted down. CDS prices for the pair still are relatively elevated — at some 10% of underlying principal for Ambac, and 6.5% for MBIA on the most heavily traded five-year CDS paper.

Both insurers made some ill-fated forays in recent years into the asset-backed-paper market, including insuring some dicey subprime-mortgage securities. But the key question for Ambac and MBIA in recent months wasn’t their survival, as the CDS market implied, but whether rating agencies might lower the credit ratings on the companies’ all-important insurance units from triple-A to double-A.

In the worst-case scenario, such a downgrade would have impaired the companies’ ability to write new business. Yet even in so-called run-off, both companies would have prospered from the momentum of large and continuing investment income and premium flow from their books of long-term insurance contracts. Both companies would have had the claims-paying ability to meet all their obligations, while also returning $30 a share or more in capital to their shareholders in less than 10 years.

Dinallo, the New York insurance superintendent, perhaps put the issue best in a letter to Congress in February that became part of the monoline hearings record: A move from AAA to AA still leaves a highly solvent, financially strong financial guarantor insurer, particularly when compared to the vast majority of other regulated insurers.

What makes CDS trading in Ambac and MBIA so intriguing is that major owners of the CDS positions have been waging open rather than clandestine war against the two companies. The charge is being led by Ackman of Pershing Square, who has been betting against the monolines for the better part of six years. Yet that campaign has borne fruit only in the past six months or so, albeit spectacularly so.

AS THE CHARTS SUGGEST, ACKMAN’S ASSAULT ON the two companies seemed to go into hyper-drive in mid-January, when he appeared on Bloomberg TV declaring MBIA would need to raise more than $10 billion in new capital just to meet its future claims obligations. Its parent company — whose credit-default swaps he held — would be insolvent anyway by the end of 2008, he charged, because of the necessity of keeping all the existing capital in the claims-paying insurance subsidiaries.

About a week later, on Jan. 18, Ackman sent a letter to the rating agencies questioning their analysis of Ambac and MBIA’s capital adequacy at the insurance-unit level. Copies of the letter were provided to the financial media and received some coverage. On Jan. 30 he followed up with a letter to regulators that cited findings from his research indicating that claims losses faced by Ambac now had risen to $11.6 billion and those of MBIA to $12.6 billion.

As Barron’s has pointed out in stories about the monoline insurers (most recently in MBIA: Priced for Catastrophe , Jan. 21), these estimates are somewhat fatuous. The numbers didn’t take into account the effect of taxes, nor the present value of claims that might take as long as 40 years to play out. Ackman’s model also relied on seemingly Draconian assumptions.

About an hour before the stock market closed Jan. 30, Charles Gasparino, a CNBC commentator with similar views to Ackman’s, stated on air that he felt in his gut Ambac or MBIA or both would be downgraded that day. Never mind that nothing happened; the shares of both companies plummeted on the news, and the leading market indexes, which had been up as much as 1% earlier in the day, ended the day down 0.3%. Ambac’s CDS prices also hit an all-time high that day.

On Feb. 5, Ackman wrote the Fed and Treasury — in a letter provided to the media — that the bond insurers were functionally insolvent, but advised against bailing them out. He also charged the New York Insurance Department was remiss in allowing bond insurers to guarantee structured products like mortgage-backed paper.

It was after this epistolary outburst that Dinallo delivered his implied warning. Ackman since has acted mainly through surrogates in the media and elsewhere to paint a bleak picture of Ambac’s and MBIA’s future. Martin Peretz, editor in chief of the New Republic and a onetime academic mentor of Ackman at Harvard, intoned in his April 2 New Republic blog, I wondered why, when MBIA showed early signs of expiring (which I believe it will still do. ) it went back to Brown to dig it out of the muck. One answer is that he knows all the secrets of the rapacious and dirty work it did. It will not help.

The Bottom Line:

The $62 trillion CDS market has become a destabilizing influence in the bond and stock markets. Rumor-mongering by CDS holders helped drive down many financial shares.

The Brown in question, Jay Brown, became CEO of MBIA again in February, after stepping down nearly a year earlier. He gently chided Peretz for failing to mention on Peretz’s blog that he was a major investor in Ackman’s fund, and therefore had a substantial financial interest in MBIA’s demise. According to Brown’s posting, there had been a dozen or more other postings by Peretz running down MBIA that lacked any such disclosure.

Ackman’s poison-pen campaign against Ambac and MBIA also inspired a hilarious parody that has circulated in recent months in Wall Street trading circles. The anonymous author, billed as Bruce Wayne, the most omnipotent Managing Founder of the Robert E. Lee Short Funds, addressed his missive to President Bush, His Holiness Pope Benedict XVl, Oprah Winfrey and Bono. It begins: You don’t know me and it is unlikely you ever [will] seek to, but I am a rich and handsome man and I have made a huge investment whose profit depends on the decline of a stock [an obvious reference to MBIA] whose issuing firm is central to the stability of global financial markets.

Some two pages later, after a send-up of Ackman’s research techniques and fear-mongering, the letter concludes: Anyway thanks for everything, thanks for just being you. Thanks for being part of a system where I can seek to systematically destroy a decades-old company that is the linchpin of the entire financing system solely to enrich myself and further my franchise as a shareholder activist, like my hero Gordon Gekko.

Ackman won’t discuss Pershing Square’s trading in Ambac or MBIA except to say his fund has made some substantial profits in both. He still insists both holding companies eventually will be toast as a result of capital starvation.

To Ackman, credit-default swaps are great, great instruments. It remains to be seen whether credit-default swaps, which often trade on raw emotion, also are good for investors in general.