An introduction to categories of bonds

Post on: 28 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Repayment date

Fixed-term bonds

Perpetual bonds

Interest

Fixed rate bonds

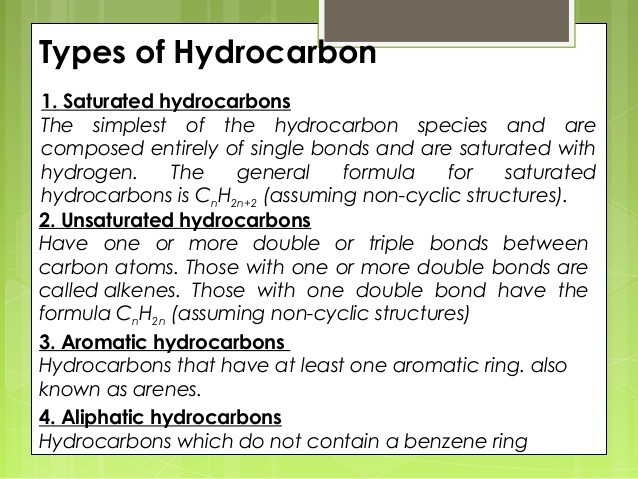

The vast majority of bonds pay a fixed rate of interest or coupon. This is calculated as a percentage of the principal and is paid on specified dates over the term of the bond. The timing of payments varies by bond. The level of interest and the timing of interest payments are important considerations in valuing a bond.

Floating rate bonds

A significant portion of the universe of bonds pays a floating rate of interest. Here the rate to be paid is not certain and is typically calculated with reference to a market rate of interest. For example, a floating rate bond might pay interest at the rate of 12 month LIBOR (a widely used rate based on inter-bank lending) plus 2%. So, the rate of interest actually paid could vary quite widely over the term of the bond. While a floating rate bond such as this offers less certainty to the investor (and the issuer) it can provide a degree of protection against interest rate or inflation risk. In a higher inflation environment, a rate such as 12 month LIBOR would be expected to rise. So, while the level of interest on fixed rate bonds wouldn’t change, the level on a bond such as this would. Floating rate bonds are particularly common in the mortgage market.

Index-linked bonds

One important type of floating rate bond is the index-linked bond or linker. Here the rate of interest is calculated with reference to inflation. For example, an index-linked gilt will normally pay a rate of interest equal to a fixed coupon plus the annual change in the level of an official index of UK inflation such as the Retail Price Index.

Collateral

Collateral is an asset or assets pledged by a borrower to guarantee fulfilment of a financial contract. An obvious example of the use of collateral for a loan is a residential mortgage. The mortgage is secured on the collateral of the house being purchased and the lender can seize the property if the borrower doesn’t make the mortgage payments. While many bonds are issued without any collateral, others are collateralised. The collateral helps to compensate for the credit risk of the bond. As well as in the mortgage market, collateralised loans are issued by corporate entities such as banks. Secured loans and covered loans are types of collateralised loan.

Seniority

Entities with multiple sources of funding (perhaps including equities and bank loans as well as bonds) need to specify which of these liabilities will be prioritised in the event that they do not meet all of their obligations. The higher the priority assigned to a particular bond, the greater its seniority in the capital structure of the issuing entity. All bonds are relatively senior to other sources of funding. For example, a corporation must pay interest owed on its bonds before it can pay a dividend to its equity holders. But different bonds have different levels of seniority.

The capital structure of a bank provides a good example of how seniority works. Banks typically issue a wide range of bonds, including collateralised bonds. But banks are obliged by regulation to meet targets on the level of capital that they must hold relative to the size of their liabilities. To do so, they typically issue some bonds which are more junior or subordinated in their capital structure and have loss-absorption features. For example, the bank may be entitled to suspend coupon payments on these bonds. Because of these features, the capital raised by issuing these bonds can count towards the bank’s capital ratio target. The market of bond investors will typically demand a significantly higher interest rate on these bonds to compensate for the extra risk of loss.

Who issues bonds?

A final and important categorisation of bonds is by issuer. Governments, public authorities and corporations all issue bonds. These different issuers have important distinctions in terms of their resources and their legal powers.

Governments

Sovereign entities (governments) raise capital through bond issuance for investment and budget financing. Different governments enjoy different levels of credit-worthiness, based on their repayment history, their level of indebtedness and the strength of their economies. But all sovereign borrowers benefit from their unique power to impose taxation on or even confiscate the property of individuals and corporate entities within their jurisdiction. Many sovereigns also control the printing of their currency. Taken together, these powers provide a high level of assurance that a sovereign issuer will make its payments.

Other public sector issuers

A range of other government sector and supranational entities also issue debt, including local government authorities, state agencies and institutions such as the European Investment Bank. These are backed by different legal powers and revenues. Some enjoy the guaranteed support of a sovereign and can be seen as interchangeable with sovereign debt. Others may not have a sovereign guarantee but have some limited power of taxation or access to certain tax revenues.

Corporate issuers

Corporations have lesser legal powers than sovereigns and must rely on the strength and reputation of their businesses when raising capital. The corporate bond market is a large and well-established part of the bond universe and it provides a deep pool of capital from which corporations can borrow to finance ongoing activities or corporate transactions. The creditworthiness of corporations is judged by the market on a case-by-case basis and will change over time. One important sub-categorisation in the market is between investment grade and non-investment grade bonds. Non-investment grade bonds (also known as high yield or junk bonds) are considered to be higher credit risk and will normally offer a higher yield to investors to compensate for this.

Important information

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.