1945 Government debt bond markets sterling and all tha The Global Financial

Post on: 5 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

October 28th, 2009

I promised to explain to Alastair, a reader of this blog the link made earlier between 1945 and todays supposed government debt crises. Sorry if its a little long but a promise is a promise.

I consider the scaremongering around government debt to be nothing more than an over-egged and salted buttermilk pudding dished up by the economic quackery of the Her Majestys Opposition. Not unlike that ancient remedy for (verbal) diarrhoea, it is intended to induce intellectual constipation in those that absorb it in spoonfuls at the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the Treasury and City of London.

We should have nothing to do with such childish prescriptions.

www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/public_finances_databank.xls) and with thanks to my colleagues in the Green New Deal group.

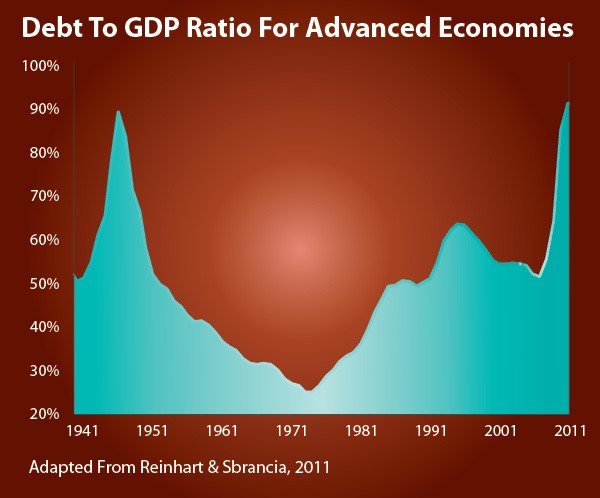

This is a chart of Britains public debt as a share of GDP from 1858 until 2002. For American readers I will paste a chart of US public debt for a similar period on my Huff Post blog in a day or two. The same economic lessons apply, even though much of the history is different.

Britains debt today as a proportion of the national cake or GDP is about 55% and rising. It is expected to hit 70% soon. Study the chart and you will see that it was twice that in 1858 about 100% of GDP.

After the outbreak of war in 1914 it started rising. The 1929 crisis caused it to rocket upwards, as indeed did the financing of a very destructive war World War II. In 1945 Britains debt stood at 250% of GDP roughly 5 times what it is today. At that point an extraordinary thing happened (largely as a result of Keynes sound advice.)

The heavily indebted Labour government began to spend as soon as legislation was agreed by Parliament.

Labour started to invest in a bold and visionary project: a publicly funded health service free at the point of use the NHS in 1946. (The American Congress is today proposing a similarly bold investment in a public option for their health service.) Back then, the Labour government carried out a massive slum clearance programme, and built houses. They revived the ancient universities, provided pensions and welfare to the poor. They trained ex-soldiers to become teachers.

What happened, you might ask, to the total public debt, as a result of this flouting of the economic orthodoxy and flagrant extravagance? Well exactly what Keynes had predicted would happen. The debt fell. Steadily, but unremittingly as a share of GDP. Look closely at the chart.

This is because government spending kick-started economic activity. (Of course it had done so during the war too but on destructive, not productive activity. That had helped defeat a profound threat Nazism but had not helped much to fix losses and generate income.)

So thanks to government intervention, economic activity revived the comatose and exhausted body that was the post-war UK economy. Soon it began to recover. With recovery, government revenues rose, expenditure on unemployment benefits fell and hey presto! government repaid its debts, which fell dramatically as a share of GDP. Soon the spending began to pay for itself.

So there you have it. Government spending encourages economic activity, brings down unemployment and hauls in tax revenues from economically active citizens, consumers and private entrepreneurs. These taxes then lower the governments debt and before you can say Nye Bevan the spending has paid for itself!

And please if another Tory or Lib Dem MP repeats the childish and tiresome mantra: just as we balance our household budget, so should we balance the governments budget just smack them on the wrists, and send them back to school.

When I a householder spend into the economy on say, insulating my property nobody rewards me by paying tax revenues into my bank account to help reduce my overdraft and balance the books. On the contrary, builders, the local hardware store, insulation experts, energy advisers drain my bank account and offer only their goods and services in exchange.

When the government spends or invests in the economy and creates jobs it is rewarded with tax revenues not just from individual taxpayers, but from businesses where the newly employed spend their earnings. Businesses that in turn use that newly-found income to spend on new investments which create more jobs and more and more taxes for governmentover, and over again! ( In economics this is known as the multiplier. It involves arithmetic dont go there unless you are good at sums.)

That is why, and how, government investment is different from household investment.

And that is why government investment pays for itself.

And to top it all, if government stops paying out unemployment benefit equivalent to say, a household stopping its contributions to an unemployed student it saves money in this case, just like a household.

Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself. (Keynes, January 1933, CW XXI, p. 150)

Oh, and two more rebuttals for those Tory and Lib Dem MPs: sterling falls when government debt rises for one reason alone: a lack of confidence in the British economy. (US government debt is rising dramatically, but the dollar rose yesterday. Why? Because investors still have confidence in the US economy.)

Anyone buying sterling can see because they read the newspapers that Britains economy is not recovering. It is still weakening. Once Britains economy recovers, confidence in sterling will recover. But the economy will not recover, unless government investment is allowed to substitute for a collapse in private investment. Once it does sterling will rise again. As night follows day.

Third and final rebuttal: the bond markets will not buy government debt government debt will crowd out private sector debt and will force up interest rates. The government will be held to ransom by the bond markets.

It is tiresome to have to rebut such arguments, but rebut we must.

The bond markets are not the King of England. They are servants to a sovereign state, begging to make a quick, safe, but effortless capital gain. (And since the financial crisis, many of these investors (like my old mother) would not dream of putting their money anywhere else except into safe UK government bonds.) Keynes advice to the British government way back then was to ignore the bond markets. Instead back in 1940 he persuaded the Treasury to oblige (perhaps the word is force) the banks some of which are today already in public ownership or part-public ownership to lend to the Treasury at very low rates of interest. The bankers were not given a choice. Their loans were given a fancy name: Treasury Deposit Receipts or TDRs and they helped to finance the war, as well as post-war economic recovery. (I am grateful to Prof Vicky Chick and Dr. Geoff Tily for these historical references.)

As the economy recovered on the back of affordable interest rates, so the banks thrived.

And a final piece of advice to the Labour government should it consider following Keyness remedies: if the banks prove difficult remove all taxpayer-backed guarantees and subsidies and embark on a heavy programme of regulation.

After all, forget not: you are the government and they owe you.